Agri-sprawl: "farming is the new golf"

I want you to bear with me today, because this one is going to be a little long.

America's best farmland is in trouble, and will only be in more trouble when the recovery comes. The American Farmland Trust, an organization I know well and respect greatly, provides some sobering facts on its website:

"Every single minute of every day, America loses two acres of farmland," and we're losing our best land - the most fertile and productive - the fastest, according to the Trust. The rate of conversion of such "prime" farmland was 30 percent faster, proportionally, than the rate for non-prime rural land in the 1990s, and there is no reason to believe that the rate for this decade will be any more comforting. The development of prime land inevitably results in an incremental shift of more agricultural production onto marginal farmland, which requires more resources like water and artificial nutrients than does prime land.

Meanwhile, our food is increasingly in the path of development: 86 percent of the nation's fruits and vegetables, and 63 percent of our dairy products, says AFT, are produced in urban-influenced areas.

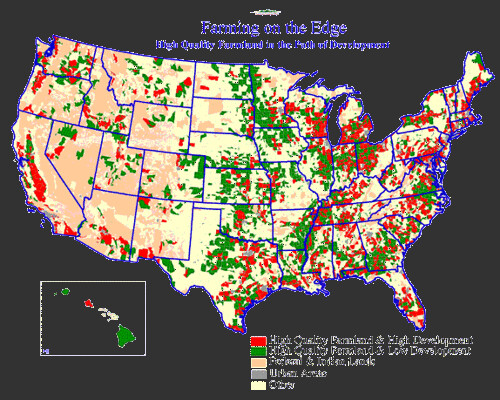

Consider this map of the US, below. The red and green areas both indicate land with prime soils, as defined by USDA and state agricultural authorities. The red areas are the ones most threatened by urban and suburban expansion. It's a lot:

The solution to providing the best protection for the resource is to keep cities and suburbs as intact and dense as possible, to limit their spread across the rural landscape. Low-density suburban development is the most inefficient in its incursions on farmland, as it is with regard to watersheds, wildlife habitat, and transportation efficiency. Beyond the developed area, we must keep the farmland as intact as possible, too. While we should incorporate community gardens and other like amenities into our new development, we should not do so in a way that compromises the average density of our overall development footprint or the contiguity of the farmland resource. This is basically Smart Growth 101.

Jane Kirchner of AFT puts it this way:

"Farmland is somewhat like habitat in that big landscapes are important and fragmentation tends to degrade the resource value. When farmland is surrounded mostly by other farmland, it tends also to be close to abundant equipment, supplies and services. When farmland is surrounded by urbanization, these resources are harder to find and more costly to access.

"There is also the matter of conflicts related to farming as a business. These can range from neighbors complaining about noise and dust, to congestion on the rural roads that farmers need to traverse to get their goods to market. For all of these reasons, agricultural land tends to be more productive when left relatively un-fragmented."

So why in the world are some otherwise progressive architects and developers wanting to expand suburban development onto prime farmland and seeking to be celebrated for creating "a powerful new model" of sustainability?

But what truly bugs me is a new argument: these guys want to make the suburban development about farming, deliberately intermingling the agriculture and the suburbs. "Farming is the new golf" is the way one proponent reportedly put it. Instead of suburban golf communities, let's have suburban organic farm communities. Because then, you know, we bring the housing out to where the food is and, just like that, we have local food. I am not making this up. Here's how it is being justified for a 538-acre mega-development of 2000 new houses in British Columbia:

"The new approach - 'agricultural urbanism' - calls for carefully fitting numerous food-related activities, including small farms, shared gardens, farmers' markets, and agricultural processing, into a walkable community.

"'What's unique about this project . . . is that we're trying to integrate agriculture and urbanism at all levels' - from high-density housing with window boxes,

to somewhat less dense houses with kitchen gardens, to quarter-acre plots, 50-acre farms, and perhaps one 160-acre farm."

There are lots of problems with this, one of the most obvious being that mixing new suburbia with farming fragments both. The functional average density of our suburbs is lowered. This creates transportation and infrastructure inefficiency for the new suburbs and, for the farming, all of the problems cited by Jane Kirchner above. Not to mention that these would almost inevitably be hobby farms.

Jane continues:

"Justifying housing in rural and ex-urban greenfield areas by building community gardens is not smart growth and not necessarily sustainable - for urban food systems or our rural and urban-edge farming systems.

"Where agriculture should be woven into the urban fabric is where it can help support high quality density.

Community gardens, edible (as opposed to purely ornamental) landscaping and farm plots on school grounds, for instance, can all add value to urban neighborhoods. These practices are still too rare and should be encouraged.

"Setting aside whole fields within development principally for food and fiber production where those fields are not also providing open-space services needed to support density is a mistake. The problem is that, to the extent that doing so requires an increase in the size of the urban service area to serve the same amount of development, farmland still loses and the environmental inputs required to further expand the road, sewer, transit and other urban systems are substantial."

In other words, "agricultural urbanism" is neither.

I suppose the leading prototype for so-called "conservation development" (of which this can be considered a new subset) is the now-iconic Prairie Crossing, built in Illinois 40 miles north of Chicago.

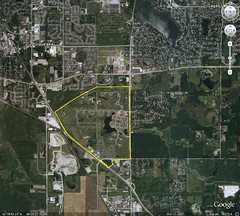

Prairie Crossing is not without merit: it includes an onsite organic farm, and at least the residents of the cluster of development at the far southern tip of the site (see below) are within walking distance of a commuter rail station. I will also grant that they did a great job on the environmental preservation aspects, and the community is undeniably lovely. It's won all sorts of awards. But dense it is not:

Note in the satellite view on the left how spread out it is (although two segments appear to be more compactly built), and note in the view on the right (identical but for scale) that the site is now surrounded by sprawl and sprawl-in-the-making. This is something that in my experience has happened around just about every idealistic new development begun with laudable qualities. Actually, much of the development now surrounding Prairie Crossing is less sprawling, because it is built more compactly.

In theory, these "new towns" are great - self-contained entities providing walkability, efficiency, and all the services of a community within the development. So, their proponents (nearly all of whom profit from them, one way or another) claim, it is a good thing to build them almost anywhere. In practice, though, the nearby once-remote locations soon become filled with sprawl, in no small part because of the initial development, and the theoretical self-contained transportation efficiency never comes. They become commuter suburbs, just with a more appealing internal design than that of their neighbors.

I do not know of a single instance where a "new town" has managed to perform even as well as the average of its metro region when it comes to limiting the growth of driving.

I cannot conclude this better than does my friend Daniel Hernandez, a longtime developer with a conscience and now director of planning for the development firm Jonathan Rose Companies:

"It seems so wrong that we're looking at . . . building new farm-style bedroom communities, which no matter how many green technology strategies are incorporated into the design to reduce environmental impacts, they do not address issues around food production, networks, and distribution in this country, not to mention the loss of prime land forever. Nor does it support nearby local economic development efforts to revitalize downtowns with existing infrastructure. Nor does it support our efforts to curb sprawl: preserved agricultural land serves as a bulwark against sprawl.

"Finally, after so many decades, policies for smart agricultural policy are just now emerging into some level of coherence, and building support.

It is clear that agricultural land preservation is critical to the economic future of our country and to feeding our country. Anything that undermines that would be irresponsible.

"Recognizing that much of this prime land around the country has unfortunately already been infringed upon, there is every reason to still support the complete preservation of these spaces. Our challenge as planners, developers and policy-makers of the built environment in an era of climate change is to figure out how to strengthen agriculture systems and biodiversity of our farmlands, and connect them to livable cities and their consumers. Our intention should be to support policies that preserve these valuable resources and strengthen their economic viability, not to assist in their destruction."

Kaid Benfield writes (almost) daily about community, development, and the environment. For more posts, see his blog's home page.

Link to original post