12 Answers to the Question of How Science Can Better Inform Your Evidence-Based Practice

Every month we feature a Global Roundtable in which a dozen or so people respond to a specific question in The Nature of Cities.

David Maddox

David Maddox, PhD. is committed to the urban ecosystem and its importance for human welfare and livelihoods. He has worked at various levels of government, NGOs, and the private sector. He is Founder and Editor-in-Chief of The Nature of Cities and hasother interests too.

Introduction

A horse walks into a bar. The bartender asks: "Why the long face?"

Countless jokes start with an introduction of odd couples and diverse sets entering a bar to set up a joke or observation about differences in perception. And so: 10 researchers and 10 practitioners walk into a bar…

Many researchers desire to see their work used in policy and practitioner action. Many practitioners crave knowledge that they can use to make better decisions or to take more effective, evidence-based action. It's a match, no?

Yet across disciplines—from biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services to community gardens and landscape design—researcher-practitioner interactions can be distant, fraught, or unsatisfying. Sometimes this is just a lack of effective fora for communication. Sometimes it is the lack of a shared vocabulary. Other times it is a disconnect of modes of working, in which researchers are rewarded for synthetic and theoretical work, but practitioners have more basic knowledge needs.

The respondents to this question include practitioners, city managers, international NGO policy analysts, scientists (biophysical and social), and designers. How can we evolve modes of interaction that advance both research and practice? Can such diverse actors co-create useful knowledge?

Charlie Nilon

Charlie Nilon is a professor of urban wildlife management at the University of Missouri. His research and teaching focus on urban wildlife conservation and on the human dimensions of wildlife conservation. Since 1997, he has ben a co-principal investigator on the Baltimore Ecosystem Study (BES).

This is an interesting and important topic, one that is certainly relevant to those of us who are trained as ecologists. This Roundtable's question comes, in part, from the way that the field of urban ecology has developed over the past 20 years. Urban forestry and urban wildlife management are older fields with a strong focus on addressing issues and problems in cities. Lowell Adams (2005) reviews the history of urban wildlife management, noting the development of urban wildlife in the 1970s and 1980s as a sub-field of wildlife ecology and management, the field's ties in the U.S. to urban planning and to state agency programs, and the strong connection to urban nature conservation programs in Europe, specifically those in the U.K. and Germany. Those programs all emphasized strong science but also application of that science to questions relevant to managers and planners. Two larger urban ecology initiatives from this period, the Man and the Biosphere program (MAB) and the U.S. Forest Service's urban forestry research program, all combined research with an applied focus on management and conservation.

The last 20 years have been an exciting time in urban ecology. The start of major research efforts in the U.S., Germany, and the U.K. in the mid 1990s brought the study of urban ecosystems into the mainstream of ecology and mainstream ecologists into cities. In the U.S., the National Science Foundation's long term ecological research projects in Baltimore and Phoenix consciously focused on addressing important ecological questions and continued their emphasis on a human ecosystem approach in studying cities. This research is important and has advanced our knowledge of urban ecosystems, but it does not always translate into information that urban residents can use or that managers can apply.

The gap between researchers and managers is in large part due to the distancing of questions that are important to ecologists from those that are important to managers, planners, and residents. Questions raised by urban residents and managers are viewed by those who fund research as "lacking conceptual focus" or as "unexciting", or simply as topics not worthy of study by serious ecologists. Peer-reviewed journals often have similar views of applied questions and ask that authors limit management recommendations to statements on what managers should consider. Finally, many university faculty view students interested in careers in management as being not quite good enough, forgetting that universities educate the large majority of managers.

But managers raise questions that are difficult for researchers. Managers are responsible for a large number of native and non-native species across a diverse landscape. Managers often work at a site-scale rather than the landscape or ecosystem scales preferred by many researchers. Managers work with constituents who have perspectives on management that are often different from both managers and ecologists, and managers work for agencies and organizations that may not place a priority on nature conservation. And, managers may not view urban ecologists and the research they do as useful or helpful.

A solution to bridging the gap between researchers and managers in cities may be in viewing conservation issues as collaborative projects that involve residents, managers, and researchers rather than just implementing management practices or conducting research. An example of this approach is Milwaukee, Wisconsin's urban forestry program's efforts to replace street trees in low-income neighborhoods. The forestry program worked with residents and with researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee to identify neighborhoods that were poorly served by the existing tree planting program. The project led to a new approach in working with neighborhoods as part of the city's tree management program.

References

Adams L. (2005) Urban wildlife ecology and conservation: A brief history of the discipline. Urban Ecosyst 8:139–156.

Louise Lezy-Bruno

Louise is Deputy Director of the Environment in the Paris Region. An Architect-Urban Planner with a PhD in Geography, she works on the cities-nature relationship. She is a member of the IUCN-WCPA.

Is it a dialogue of the deaf?

In 2010, during the BiodiverCities conference we organized in Paris, I heard the manager of a national park of a large city in East Africa say that he and his city official counterpart had met for the first time on the plane to come to Paris. Two administrations, two jobs, with no conversation between them. But both had already met the researchers who came to ask both park managers and city officials questions about their fields.

The objective of this conference was, precisely, to gather around the table cities, parks managers, and the researchers working on the relationship between cities and parks. The researchers assumed the role of middle ground between the different tribes of managers.

But at the end of the conference, there was still a hint of disappointment in the air: the practitioners (in cities and parks) had presented the results of the actions they had managed to set up and the researchers had analyzed, even criticized, everything that had been accomplished…No wonder! The researcher is there to raise questions, the practitioner, to find solutions.

They are made for each other, it seems! Both are needed to develop an applied research process, even if they each intend to call into question the certainties of the other party. In practice, the researcher is the "troublemaker on duty" that comes into the practitioner's field to analyze everything that goes wrong. The practitioner breaks his back to find solutions, which are inevitably a compromise between local knowledge, social demands, political pressures, limited human resources and budget constraints. In his mind, he has just resolved the squaring of the circle. Of course, he doesn't greet the "researcher of problems", coming into his field to give him lessons on what is good and what is not, with pleasure.

How can we be sure that the theoretical analysis of the researchers can be working tools for the practitioners? How can independent research support operational choices on the field?

We need to be more malleable with each other, more attentive.

For me, the answer is like cocktails: varied recipes produce different effects. The "Caipirinha" and the "Sex on the beach" are different. First, it is a matter of substrate: in the hot alcohol, the cachaça, and in the iced alcohol, the vodka, produce different results. The ingredients of the first are mixed in a shaker; in the second, the difference in densities of the ingredients makes up the whole. In the end, both results could be very good.

In other words, there is no single recipe for the dialogue between research and operational practice. We must simply have a common goal towards which to combine our different ingredients: either the mixture of different components forms the whole, or the superposition of the strata supports the entirety.

For example, long-term research deepens the questions that the immediacy of practice does not allow. In turn, the practitioner provides the fertile ground for the production of the researcher. In this way, the results of the scientific research should be able to fertilize the management practice. The wealth and independence of scientific research should be the substrate of practitioner action, the elements combining to both inform and support decisions. Likewise, the application of theory in practice enables checks of the theory's validity.

In addition to basic research, the academy could incorporate more applied research. But it should also develop tools to disseminate scientific information and translate scientific language into technical and popular languages. We could develop more research programs associated with field actions, with research funding, or with orders from the field stakeholders.

By de-compartmentalizing academic and operational fields and promoting teamwork, we can make researchers, practitioners, and decision makers work together.

The trick is to know how to combine the minds and the spirits, and we will have a good cocktail!

Keith Bowers

For nearly 30 years, Keith Bowers has been at the forefront of applied ecology, land conservation and ecological restoration. As the founder and president of Biohabitats, Keith has built a multidisciplinary organization focused on regenerative design.

More than once, while enjoying a pint with a group of my fellow restoration researchers and practitioners, I have wondered how many of us occasionally covet each other's jobs. Don't get me wrong, as the leader of Biohabitats, Inc., my passion and vocation is the practice of ecological restoration. But when I talk to researchers, I sometimes find myself thinking: "I wish I had the time and resources to integrate controlled, replicated experiments into all of our work." And conversely, I suspect that my research colleagues may occasionally think: "How cool. I wish I had the time to participate in the design and implementation of restoration projects like Biohabitats does".

Practitioners and researchers are united in so many ways. Our passion for restoration, our desire to continually improve the success of ecological restoration and our aspirations for healing damaged or destroyed ecosystems keeps us all going. Why, then, is our work so often disconnected? Although Biohabitats includes dozens of team members with academic research experience, and we often attend scientific conferences and review the latest journal articles, we seldom come across academic research that can be directly applied to our current body of work.

Conversely, while we have so many lessons learned to share from the design and implementation of hundreds of projects, we neither have the time nor resources to publish the work. And even if we did, we would most likely not meet the standards of peer-reviewed journals. In our daily work, Biohabitats rarely has the opportunity (time and funding) to embed experimental designs to evaluate hypotheses in an academically rigorous way, and our colleagues in universities rarely address the myriad constraints that we encounter in the real world of implementing restoration projects.

How can we let this continue? If there is one thing we know for sure, it is that the problems our work tries to solve are substantial and mounting. And as a society, we don't have the time or resources to perpetuate failure. We need practical solutions based on rigorous science now.

We need practitioners informing experimental designs; we need researchers working with us to evaluate projects; and we need to pool our resources to find the best solutions out there. Some of these challenges can be addressed by purposeful collaboration between private companies and like-minded universities and research institutions. Others would benefit from third party support, such as grantors that explicitly require collaborations that bridge not only disciplines but also sectors.

In response to these felt needs, Biohabitats recently created Bioworks, an intra-disciplinary practice dedicated to integrating robust research into the practice of ecological restoration and conservation planning. Our goals are threefold. One, to develop hypotheses and embed applied experiments into all of our work, thereby establishing a rigorous foundation for collaborative research with universities, research institutions and non-government organizations. Two, team with these same organizations to purse funding to jointly research cutting edge solutions to some of our most pressing problems in achieving successful outcomes for ecological restoration. And three, to widely share this information in a practical, easily accessible way with the thousands of practitioners that are toiling day-to-day in the rivers, wetlands, woodlands and fields across the planet.

We know this important work cannot be done alone in a silo, by a single entity, institution or discipline. So if you are interested in joining this collaboration, join me for another pint and let's make this happen!

Amy Hahs

Dr Amy Hahs is the GIS Ecologist at the Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology, Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne.

In my personal experience of integrating science and practice, the best discoveries and insights have emerged through the direct interactions and conversations with other members of the cast, who come from different disciplines, institutions and perspectives. Therefore, while I think there are some opportunities to improve the way actionable science knowledge and outcomes are shared between groups, I strongly believe that the engine room for change and evolution will be at the level of individual interactions.

When it comes to these individual interactions, how would I describe the ideal scenario? I think that open channels of direct communication are critical, and they need to be ongoing. There may be great interactions and collaboration over the course of a project, but too often they effectively stop once the project has been delivered. The evaluation of the project itself, and the process that was undertaken, then ends up being conducted internally within individuals or perhaps disciplines, if it happens at all. This means that we are missing out on an important opportunity to continue learning and evolving our modes of interaction. We need to look for ways of making this feedback and evaluation stage a common element of project delivery wherever possible, either through formal mechanisms (i.e., written into the proposal) or informal mechanisms (committing to catch up for a coffee and chat shortly after the project delivery).

A common communication loop I have experienced during projects integrating science and practice. Most of the communication and learning (thick arrows) occurs during the project itself, and rarely during the evaluation stage (narrow arrow). An ideal scenario would see a much greater volume of interactions occurring outside of the project phase, either as a debriefing session focused on that specific project, or as a longer ongoing conversation.

We also need to find ways of respectfully expressing feedback and initiating dialogue around the things that didn't work. These conversations may be difficult, but they are imperative if we are to address any tensions arising from institutional or disciplinary perspectives.

Steven Handel proposed that ecology and landscape architecture are in a period of their relationship where marriage therapy may be required. Relationships between people can only fully evolve if we are willing to share our full experiences, and we are committed to listening and working through our differences.

One idea which may help navigate these differences would be to think about disciplines as producing paintings with different styles. We become very good at recognising and interpreting the key features within the paintings we are familiar with, but it is more difficult to interpret works produced in a contrasting style. If we are experts at Impressionist landscapes, it is difficult to understand how to incorporate Romantic portraiture into our work. This is where the ongoing dialogue between diverse actors is critical. The best outcomes will emerge when we can become better "art historians" and increase our fluency of interpretation across a broader range of painting styles. This shared understanding may even lead to an entirely new movement, with a style all of its own.

When it comes to more formal avenues of communication, I suspect there is something about the process of peer review, as well as the expectations of journals about what is "of interest", that limits the type of information and learning that can be shared in these forums. Personal conversations may continue to be the most effective way of sharing this information, and often can occur at conferences and other settings. Options for increasing the number of participants in the conversation may involve online fora and other activities that make the most of our sophisticated virtual technologies.

Something to keep in mind throughout these discussions is that some actors may not have the means or desire to navigate new disciplines. This means that a person who does enter this interface of science and action essentially becomes an Ambassador within the different realms. Amongst our colleagues and peers we may become a point of contact for others who are interested in engaging with this collaborative model of thinking and working. When we visit the realms of our counterparts, we help to bridge the divide between disciplines. If we continue to do our jobs well, then we will not only deliver better outcomes ourselves, we will also have helped to grow the momentum of effort in this area.

Evolutionary change often occurs in response to pressure. Our current efforts to integrate science and practice have evolved in response to the pressures of developing sustainable, resilient, biodiverse cities and towns. The evolution within our efforts will be shaped by the internal pressures related to how this diverse range of actors start bringing together their different perspectives to deliver outcomes that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Philip Silva

Philip's work focuses on informal adult learning and participatory action research in social-ecological systems. He is dedicated to exploring nature in all of its urban expressions.

Let's imagine that the scientists at the bar are out celebrating a new publication in a prestigious academic journal and the practitioners are celebrating the successful completion of a big environmental restoration project. Both groups raise their glasses to mark the end of two different knowledge-intensive processes. Their methods for creating new knowledge may be similar, such as natural resource managers using environmental sensing tools to collect data on the outcomes of their restoration efforts. But practitioners and scientists have different motives in their work and different rewards for a job well done. They make different kinds of knowledge for different purposes and they have different long-term expectations for the knowledge they produce.

We often speak of science as if it has a monopoly on the process of making new knowledge. Yet not all knowledge is scientific knowledge. Not all claims made on the basis of observation and evidence are exclusively scientific claims. Not all knowledge is codified using scientific standards, such as blind peer review or reproduction of research results. Science creates scientificknowledge. Other processes and practices produce other kinds of knowledge. We might debate whether science is an exceptional way to create exceptionally reliable knowledge or whether it is just one of many different methods for constructing stable meaning out of the chaos of reality—but that's a debate for a different forum. For now, let's just agree that knowledge making isn't solely a scientific endeavor.

Harry Collins (2007) argues that, "Science, if it can deliver truth, cannot deliver it at the speed of politics." Practitioners are often faced with day-to-day puzzles that go far beyond the knowledge found in textbooks or journal articles. Laws are passed, ecosystems are restored, polluters are punished, and natural resources are managed on the basis of sound scientific knowledge. Yet in plenty of cases, practitioners have to learn as they go and create their own useful insights into the problem at hand—either because the knowledge produced by science is incomplete or, in cases of complex and emergent systems, because the science doesn't match reality. Waiting around for science to catch up with the chaos can lead to disastrous results, as Brian Wynne (1996) showed in his study of sheep farmers and regulatory scientists in northern England struggling to manage radioactive fall-out from Chernobyl in 1986.

Knowledge for management needn't make a detour through the methods and conventions of science. It can, and often must, find its own path. When we speak of practitioners and scientists getting together to co-produce knowledge, we shouldn't always give priority to the co-production of scientific knowledge, forcing practitioners to carve out a space for themselves in the practice of science and rarely expecting the same of scientists in the service of management. Funtowicz and Ravetz (1991) proposed the idea of "post-normal science" to deal with these issues nearly a quarter century ago, and though they came close to honoring the practical knowledge that comes out of daily management, they nonetheless created a theoretical framework that shoehorned all forms of knowledge production under the heading of science. Mainstream science, in return, has largely ignored their prescriptions—and rightly so. Science is science. Post-normal science is, well, something else; something like the knowledge making practices we see at play in day-to-day environmental management.

I'd like to see more practitioners becoming aware of the knowledge-making and knowledge-managing dimensions of their work. They may find useful insights and ideas in the knowledge that comes from science, but they also need to see themselves as insightful puzzle-solvers with wisdom to share with others in their fields.

In turn, I'd like to see scientists grow comfortable with the notion that other forms of knowledge production can bear a striking to science without having to actually be science. Intellectually informed management and epistemologically humbled science? It's hardly an inspiring toast to rally our revelers, but all the same, I'll drink to that.

Rebecca Salminen Witt

Rebecca is the President of The Greening of Detroit, a 25 year old non-profit environmental organization that works to secure the ecosystem of Detroit.

Consider this recent interaction between a medical researcher and a community leader in Detroit, Michigan:

Researcher: "We are currently studying the interaction between chemical and non-chemical environmental stressors in urban environments. We are planning to study the construction of Detroit's new light rail system in this context. How can we engage nearby neighborhoods in our research?"

Leader: "Well, my neighborhood is not located along the new light rail line. All of the investment in this City is happening downtown. We need resources in the neighborhoods. We are constantly being studied, but no one is offering us any resources. Y'know what I'm sayin'?"

Both the researcher and the community leader are working to improve Detroit's environment. Both are committed and passionate about their work. Each could be helpful to the work of the other. But clearly, they don't have a common starting point from which to develop this potentially fruitful relationship. They aren't even starting in the same neighborhood, much less walking into a bar together!

This exchange gets to the crux of our focus question. How can we fortify the hyper-local and generally self-interested work of the practitioner with the work of researchers dealing with theoretical concepts often designed to be applicable in a global context and rarely grounded in individual realities?

First, identify common ground. The researcher in this example wants his research to help reduce stress-induced disease. The community leader wants her neighborhood to benefit from the economic development that is the source of the stress that the researcher is studying. Could the researcher study the stress caused by being "left out" of the surge in economic development happening in other parts of the City? Could the Community leader draw attention to the needs of her neighborhood by participating in the study? If they were discussing this over a beer instead of in a conference room, would the conversation be more productive?

Next we should examine the language that these partners are using. Remember the community leader's question in my example "Y'know what I'm sayin'?" Without thoughtful consideration of the language that they are using in their conversation with one another, neither one of these Detroiters is likely to know what the other is saying. The community leader is looking for resources to get vacant houses demolished and the empty lots mowed on her block. She hasn't got the slightest concern for the "chemical and non-chemical environmental stressors in urban environments." Yet she is clearly impacted by the environmental stressors in her neighborhood, and would likely benefit from the results of the proposed research.

Similarly, the researcher needs data, and just wants to talk to some real people who are likely to be affected by his target stressor. If the researcher had simply asked to chat about what was causing neighbors to stress out, he may have engendered a more helpful response. The community leader may have been able to recognize that she is suffering from stress brought on by her environment and might have seen some personal relevance in the research, leading her to participate. Similarly, if the community leader had focused her response on the proposed research instead of the needs of her own neighborhood, she may have found that the research was a resource in its own right.

What this conversation needs is focus and plain language. The next time these two walk into a bar together, I hope they'll order a beer, take the time to figure out where their interests overlap, and work hard to communicate clearly about opportunities to pursue their common objectives.

Maria E Ignatieva

Maria Ignatieva is Professor of Urban Ecology and Design at the Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences. Maria's current interests include 'putting nature back into neighborhoods', theoretical, methodological and practical approaches to sustainable landscape design in the era of globalization with an emphasis to urban biodiversity and design.

How can our scientific research can be effectively used in practice?

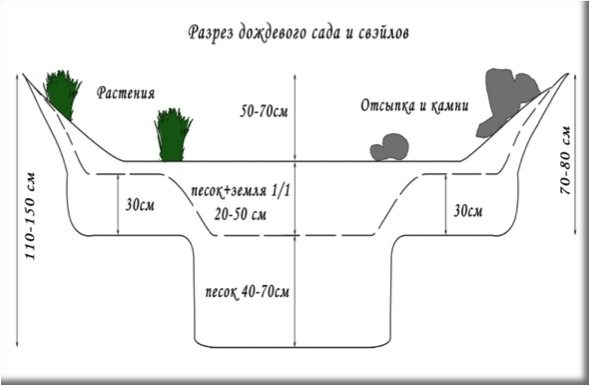

Rain garden (top) vs. Conventional local cleaning facilities, CLFC (bottom, showing reconstruction of engeneering networks and elements of stormwater sewage). Rain gardens are much cheaper and do not need special legal agreements. They help decrease the pressure to CLCF for up to 80-90 percent of surface water. A rain garden is a landscape architecture (LA) design element compared to CLCF, which needs special LA design considerations.

Use of research results is one of the most desirable slogans in modern landscape architecture. However, the most difficult questions is how to "translate" the research results and make them understandable not for only practitioners such as city planners, landscape architects, or engineers, but for city administrators and politicians who make final decisions and proof the cities' budgets.

Actually, in all grant applications today, scientists are required to think about communications of their results with a stakeholders. I would like to share with you one example, in which I was involved directly, with such a "translation" of the research into practice in a real neighborhood in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Here a group of young landscape architecture practitioners (Andrey Bashkirov and Sergei Shevliakov) were inspired by my lectures for master's and PhD students about new ecological designs, particularly on implementations of Low Impact Design—an environmentally friendly ecological design approach aimed at managing urban stormwater and promoting biodiversity. The area of Novoe Devyatkino neighborhood, with multistory residential buildings, required immediate help due to flood issues in common green areas. In 2013, the landscape architecture firm Sakura presented a concept design based on the introduction of LID devices such as rain gardens. Realizing that LID requires an interdisciplinary approach, social research (questionnaires, interviews, and observation studies) were also conducted in the summer of 2014. The analysis of these questionnaires has shown the importance of water (a lake). The majority of people valued the lake as a major attraction and expressed a need for the development and improvement of the shoreline. People found rain gardens very attractive and were satisfied with their appearance and conditions.

Rain Garden. June 2014

Social survey (Biana and Tuula). June 2014

From the very beginning of this project we realized that the most effective tools for attracting politicians, administrators, and contracts was the economic factor. That is why the conceptual design was combined with a calculation of costs. Our economic research comparing costs of design and implementation of traditional waterstorm management practices and LID practices (rain gardens and swales) clearly indicated that rain gardens are much cheaper and do not need special legal agreements (figures above). They help to decrease the pressure on Conventional Local Cleaning Facilities (CLCF) for up to 80-90% of surface water. A rain garden is, in itself, a landscape architecture design element compared to CLCF, which need special landscape architecture considerations. The cost of creating the rain garden was 1557 rubles (including plant material) compared to 1862 rubles per hectare for conventional facilities (not including design, legal negotiations, and plant material costs). The management costs of LID new devices are also very low compare to traditional methods.

Team work of young administrator Olga (on the left), landscape architect (Andrei) and the researcher (Maria). November 2013.

One of the conclusions of this project was that conventional thinking is still strong in Russia, but young administrators are more open to new, innovative designs, especially when they can see an economic profit. We also found out that for the success of the new LID practice, it is crucial to educate contractors and implementation teams in the "right" management approach.

Other positive lessons from the realization of the Novoe Devyatkino project were the introduction of a social survey practice (directly involving local citizens in the design and management process) and the implementation of educational boards. The positive attitude of local administrators and local citizens toward this innovative landscape architecture practice gives us hope for the introduction of LID into a wider urban context within Russia.

Reference

Bashkirov, A., Shevliakov, S., Petter, B., Irishina I., Eriksson, T., Ignatieva, M. (2015) Implementation of Low Impact Design (LID) in Russia. In: M.Ignatieva, N. Thorne, E.Golosova, P. Berg., P. Hedfors, T. Eriksson, D. Menzies (eds). History of the Future. 52nd World Congress of the International Federation of Landscape Architects Congress proceedings. 10–12 June 2015. Saint-Petersburg, Russia. Peter the Great Saint-Petersburg State Polytechnic University Polytechnic University Publishing House, St. Petersburg. Pp.22-23.

Georgina Avlonitis

Georgina Avlonitis manages ICLEI's Urban Natural Assets for Africa Project, designed to improve human well-being and resilience of the urban poor. She enjoys dabbling in graphic design, story-telling and visual communication techniques and is madly in love with her red vintage racer bicycle.

Some 'Touchy-Feely' Stuff at the Bar

During my post-graduate years studying urban ecology, I eagerly ranted about my research findings to city officials and to my dismay, I watched eyes glaze over and feet start to shuffle as the communication disconnect set in. This was not due to any lack of fervent intonations and gesticulations from my side—I was convinced of the importance of my findings—but I was, of course, focusing on all the wrong aspects of my work. It may as well have been a soliloquy in Greek. And now, during my professional career, I realise I could not blame them, because when forced to sit in a room of scientists debating complex and unfamiliar methodological approaches, I've ashamedly found my mind beginning to wander and my feet doing that same shuffle, while half expecting my head to explode.

Street art by Mark Samsonovich.

Scientists and policy-makers certainly do all sorts of 'talking': they talk at each other, on top of each other, about each other, past each other. More often than not, they speak across each other—speaking about the same issues, but in completely different languages. For example, scientists often define evidence from a methodological perspective while policy makers define evidence from a relevance perspective—this is why policy priorities often drive the use of research, rather than research stimulating policy recommendations.

But how to create bi-directional, collaborative communication, where scientists and policy makers communicate with each other?

I could write about suggested solutions such as: the use of third party science-communicators; how to jointly involve decision-makers and scientists in all phases of research, including the development of the questions and the interpretation of results; or approaches for the development of effective platforms for dialogue—but we're still not addressing the heart of the issue: that collaboration and co-creation needs connection. Which is why I'm choosing to focus on something a bit 'softer' and much more fundamental.

If I had to stick policy makers and scientists into a hypothetical bar, I'd probably first hand them over a strong whisky, to soften the edges and loosen them up a bit. Then I'd get them to speak about what makes them passionate about what they are doing and then—no cringing allowed—I'd get them to make themselves vulnerable. And by vulnerable, I don't mean walking around with a box of tissues crying about things. I mean having an open conversation about some of the deeper, more human, more visceral elements of work: explaining where you're unsure; talking about the complex challenges that wake you up at 2am; describing what gets you out of bed in the morning to go to work; explaining what excites you or completely devastates you about the field you're in.

More often than not, vulnerability and passion are the links between the science and policy arena—it's where the bravado dissipates, where the commonalities lie, where the challenging, exciting realities surface, where humanity is exposed; it's where the conversation opens up and where the ground is leveled for better relationships, for honesty and communication. It's something as simple as admitting: 'I don't know what I'm doing right here, with this.'

Policy-makers typically aren't interested in science per se (although some are); they are interested in research evidence insofar as it helps them to make better decisions (because without adequate information—let's be honest—they wouldn't really know what they were doing). Scientists are enamored with their fields of inquiry and, coupled with an interest in promoting their work and ensuring research funding, this can sometimes lead to convoluted reporting of results and, very occasionally, exaggeration. But ultimately, if policy makers and scientists could open up about where they are unsure, could make themselves vulnerable around the effectiveness of their work and decisions, could share the real reasons why the potential impact of their work excites them (or doesn't)—therein lies the connection! Only then can parties help to better fill the gaps, to reshape the objectives, and to enhance the relevance and impact of each other's work.

Some 'touchy-feely' suggestions:

- Reinvent the meet-and-mingle: Formalise more informal networking events/sessions where individuals from science and policy arenas can socially interact in your institutions/departments and most importantly have fun while doing so.

- Personal relationships run the world: Take some time to get to know scientist/policy-maker peers, before launching into hard work-talk. Look for a common spark and learn what really matters to them and how you can help. It goes without saying that people are more likely to want to engage in your work if they feel a personal affiliation with you.

- Stick your neck out: Be interested and ask more questions. "You can make more connections in two months by becoming interested in other people than you can in two years by trying to get other people interested in you." — Dale Carnegie

- Get outside: There is no better way to remember why it is you're doing what you're doing and share some common ground than by taking meetings/workshops into nature. (It also boosts creativity and productivity.)

- And lastly and most definitely, build in more time at the bar: This goes without saying.

Michael Jemtrud

Michael is an Associate Professor of Architecture at McGill University and Founding Director of the Facility for Architectural Research in Media and Mediation (FARMM).

A Case for the Counterfactual Project

There are moments when a problem quite simply has to be solved and consolidating resources and expertise is a relatively straight forward, sensible, and effective thing to do. There are numerous examples in which researchers effectively collaborate with practice, industry, and government to solve problems (see Note). However, the "pragmatic efficacy" of instrumentally linking research and practice has significant limitations in imagining alternative futures, practices, and ways of acting in an era defined as the anthropocene. It is here I would like to make a case for the counterfactual as a productive and mediating mode of collaboration between research and practice.

As Graham Harman states, "pragmatic success often occurs on the basis of half-truths or outright falsehoods. In such cases we do not always leave our theories intact simply because they seem to be working. Quite often, we change our theories to give them wider applicability and a better capacity to handle possible surprising cases." He goes on to say, "Architecture might make theoretical decisions that are unnecessary in the current practical state of the art, for the simple reason that truth has a greater power, reliability, flexibility, and allure than mere practical success" (Harman 2013, p. 213).

Research-through-design is a formally recognized methodology of inquiry that is productive and characterized by its fabricative nature. Proposals are made and outputs are varied, from drawings, models, simulations, and time-based representations to policy and strategic documents. In its most potent form, it is an inclusive, multi-stakeholder, cross-disciplinary, project-based activity. As such, it is messy and gains its value as research and practice from this messiness. It is most often context specific and accepts the inevitably contested constraints, concerns, and worldviews brought to the table by the participants. As a productive mode of inquiry, it is self-aware of the fact that "praxis distorts the reality of things just as much as theory" (Harman 2013, p. 211).

Engaging in "What if? scenarios" can occur at a variety of levels, either historical reconsiderations or future propositional. For example, speculation ranges from the formalized and sensible "Urban Futures Method" for designing resilient cities to the utterly fantastic and counterfactual (Lombardi et al. 2012). Collaborating in this manner is a way of dragging the real world into the academy and the academy into the real world. It is a distortion of the conventionally formulated problematic wherein problem solving is surpassed but not left behind. Significantly so, research that embraces the counterfactual is a mode of provocation that agitates the disciplining inherent to disciplines. Like Harman, I am encouraging the counterfactual in all fields of inquiry. It is a critical device in collectively imagining what we ought to do, not merely what we can do.

Note

It can be argued that this is in fact the predominant model of research in the academy since WWII signaled by Eisenhower's famous military–industrial complex speech in 1961. Suffice to say, this is not the place to get into the corporatization of higher education but it is a significant factor lurking behind the question at hand. Also see: Readings, B. (1997) The University in Ruins. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Chomsky, N. (2011) "Academic Freedom and the Corporatization of Universities". Online at:http://www.chomsky.info/talks/20110406.htm[Accessed 11 December 2014]: "it seems pretty clear that the shift toward corporate funding [for research in universities] is leading towards more short-term applied research and less exploration of what might turn out to be interesting and important down the road."

References

Harman, G. (2013) Non-Relationality for Philosophers and Architects (2012). Found in Bells and Whistles: More Speculative Realism.

Lombardi, D.R., et. al. (2012) Designing Resilient Cities: A guide to good practice. Watford, UK: BRE Press.

Haripriya Gundimeda

Dr. Gundimeda is a Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay. Her main interests are green accounting, mitigation aspects of climate change, energy demand and pricing, valuation of environmental resources, and issues relating to the development in India.

What does it mean to make the two ends—biodiversity science and policy making—meet?

Scientist: Biodiversity is very essential for life. However, we are losing it at a faster rate than before and the number of endangered and extinct species are increasing. For conserving biodiversity, the underlying biological processes need to be understood well and adequate emphasis has to be given to building stable and resilient systems.

Practitioner: Yes, biodiversity needs to be conserved, but the goal is harder to achieve than to say. Biodiversity is not just a mere collection of individuals, but is characterized by highly complex and nested interactions among the species. Further, the complexity of scale and level of organization makes it more complicated to build into the planning process. Do we have some rules to set conservation policies and what conservation requires?

Scientists: We need habitat inventories for the presence and abundance of various dominant and associated species.

Practitioner: Given that there is dearth of ecologists, can we meaningfully inventory all the habitats? How can we decide which is more important—bryophytes, invertebrates, mosses, lichens, vascular plants, etc.? Do we have closely aligned practical indicators to measure the success of various conservation efforts?

Scientist: One can measure the success of conservation in already protected areas through measuring changes in the number and relative abundance of species—keystone, flagship, umbrella, threatened, endangered, endemic, and focal species—and the distribution, turn over, diversity, and quality of ecosystems. However, it requires time and resources. Numerous measures may have to be identified. Classify the areas as risky and non-risky areas and ensure full conservation in risky areas.

Practitioner: It is not possible to carry out inventories in all areas; protected areas may have some of the above indicators already, but what about areas which are not protected, yet are important. Resources are limited, and there are trade-offs. Can we use some criteria? For example, we say biodiversity should be conserved because it enhances the well-being of people now and in the future. Can we look at nature as providing ecosystem services to people and should we be considering the economic value of these benefits to people? Such an approach helps policy makers in prioritizing areas that provide maximum benefits and also justify investments.

Scientist: We differ. Ecosystems are complex and the services are not separable. Moreover, values are dynamic and change as the structure of society changes, despite that ecosystem services remain the same. Moreover, there may be conflict in this case as the ecosystem service provided in many cases may not have market value attached. Quantifying cultural, spiritual, and existence values is difficult. The studies are still limited and it is possible that pristine ecosystems are left out. This would have deleterious impacts for the conservation of ecosystems.

Practitioner: Yes, we agree that there are trade-offs in functions provided by ecosystems and prioritizing one would be at the cost of another. But we need a metric to measure what to conserve and the outcome of our actions. How to measure the outcome and the actions needed to conserve for effective policy making? We need something which is cost-effective. Can scientists offer right indicators and legitimate criteria to choose one area above another?

Scientist: Yes, it is a bit difficult, complicated, and contentious, but we agree that the scientific community needs to mobilize to design programs and indicators that are pragmatic to support conservation decisions. Probably while we get the right science and science right, can we at least agree that biodiversity conservation is an integral part of development plans? And can we rope in private communities to finance conservation?

Practitioner: Yes, whatever it means to make both the ends—biodiversity science and development policy—meet.

Fadi Hamdan

Fadi works on the interaction between risk governance and communication, disaster risk management, resilience, sustainable development, growth, and use of resources in cities.

Several scientists and practitioners walk into a bar. After deciding on drinks, they began discussing how research and knowledge generation can better support evidence-based decision making.

One of the scientists, who is trained to make a hypothesis and then to test it either to confirm its validity or modify it accordingly, started the conversation by making an assumption that scientists rarely bother to test. Namely, the scientists believed that they do not take any decisions, they simply apply scientific tools effectively and objectively. It is the fault of "practitioners" or "decision makers", who are not always capable of understanding the scientist's "objective" scientific advice, when things don't go smoothly.

One of the practitioners commented that decision makers come in different shapes and forms. But they all know that the decision making process is far from straightforward; even in the best of the functioning democracies, the decision making process is subject to gate keepers, as well as legal and illegal lobbying and legal and illegal modes of expressing and withdrawing support. And that was even before the age of globalisation, whereas nowadays, big capital and large multi-nationals can more easily void or threaten the prospects of effecting change as a result of a democratic election simply by threatening to withdraw their support, including in terms of investments and jobs.

That is why we find near unanimous agreement that the decision making process in any field must be subject to a governance framework, with checks and balances to ensure that all perspectives and points of view are being accounted for "as far as reasonably practicable".

Another practitioner agreed and gave an example from the field of Disaster Risk Management, where there is agreement that the decisions related to the use, production, and distribution of natural and government resources (e.g. water, land, tax payers' money, air, etc.) lead to a particular distribution of benefits, exposure, vulnerability, risks, and, increasingly, disaster losses. Furthermore, these benefits and associated exposure, vulnerability, risks, and losses are unequally distributed between sectors (e.g. industrial vs. agricultural or, increasingly, financial vs. industrial and agricultural). They are also unequally distributed between countries (if we look at the earth resources as a whole) and, indeed, within any country. That is why, in functioning democracies, these decisions are, as far as reasonably practicable, subject to scrutiny that practitioners like myself call a "Risk Governance Framework".

Another scientist agreed that scientific advice is not always subject to the same scrutiny within this Risk Governance Framework. She gave an example of the decision to construct a risk map for a particular hazard in a city (e.g. earthquakes) that accounts only for the physical and natural factors contributing to vulnerability (i.e. severity and frequency of earthquakes and the state of building and infrastructure stock). Such a map is based on a decision that it is acceptable to ignore the social, economic, and institutional factors that contribute to vulnerability. She continued that this is equally true in other cases for other hazards affecting cities, including flooding, storms, sea surges, drought, etc.

Another practitioner commented that, in many instances, we end up with a situation where the decision makers know they are right, the scientists believe they are right, and affected people living in cities with deteriorating infrastructure feel something is not quite right.

After a few drinks, the scientists and practitioners agreed to ask non-specialists, their fellow citizens, sitting in the bar for their perceptions. Based on their reaction, most of the two groups then agreed that to improve the science-policy interface, to promote evidence-based decision making, and to account for societal apprehensions and concerns, decisions and recommendations provided by scientists should lie within the Risk Governance Framework.

Ian MacGregor-Fors

Ian MacGregor-Fors is a researcher at INECOL (Mexico). His interests are broad, but he focuses on the responses of wildlife species to urbanization.

Science and its diverse disciplines have both basic—or fundamental—and applied components. On the one hand, basic science relies on the exploration of unknown phenomena regardless of the potential applicability. The reason behind focusing on any given phenomenon, hypothesis, or topic in any basic science research varies from mere curiosity to continuation of previous findings in a similar line of thought. Applied science seeks to address specific needs or to solve practical problems based on preexisting knowledge gained through basic science research. However, there are cases—occurring more frequently in recent decades—where basic and applied sciences work together to generate the new information needed to tackle specific concerns from scratch.

Currently, planet Earth is experiencing important changes that have resulted in unprecedented environmental and social disasters. Poverty, water insufficiency, food scarcity, disease epidemics, climate change, and pollution, among other devastating problems, are at the top of the list of news headlines. Among other factors, this has resulted in a biased perception of science as a problem solving activity, setting aside and, often, excluding some of its most fundamental expressions. I agree that the basic/applied science ratio is dynamic and responds to a complex array of external factors; yet, some of those driving forces could tip the ratio out of balance.

The path that runs from generating scientific knowledge to its potential immediate application, if any, can be as diverse as the universe of evidence-based findings. It is important to underline that for scientific knowledge to be applicable, it needs to be robust and sufficient to integrally solve a given problem. Robustness of science usually depends on the spatial and temporal scale of its design, which often requires more than a single view to represent the nature of the phenomenon being studied. So not only are multiple studies generally recommended to have a complete enough picture of the tested hypotheses or described phenomena, but diverse views—venturing into the multi-, cross-, inter-, and even trans-disciplinary schemes—are also necessary to successfully achieve the desired results.

From my perspective, the cornerstone of scientific knowledge application is willingness from all implied stakeholders. Aside from the actors facing the problem, there are two other main components involved in this process: scientists and practitioners. One important ingredient behind the complexity of applying evidence-based knowledge is the number and type of involved actors. The number of scientists and practitioners needed in solving a practical issue generally depends on the magnitude or specificity of the problem. Although it may seem intuitive that having more actors solving a problem could increase its probability of success, it can also escalate potential complications. Something similar happens with the type of scientists and practitioners involved in the application of knowledge to address a specific need, where a trade-off arises as the degree of complexity increases due to including multi- to trans-disciplinary approaches. Nonetheless, emerging additional actors joining this interesting equation are currently bridging the gap of complexity when large and diverse stakeholder groups are required to address a specific problem; the most important of these additional actors are "evidence-based knowledge translators"—a blend between applied scientists and decision making practitioners.

Once the actors are defined and all parts share a common goal, an initial step could be to search for preexisting studies that could shed some light on the matter; there is an overwhelming amount of top-notch knowledge gathering dust in science journals! I am not suggesting that preexisting knowledge is generalizable and ready to use; however, it could represent a basis to depart from, saving valuable time and resources. Also at the initial stages of a project, languages—including technical ones—need to be equalized if one primary objective is to level the comprehension of all edges of a given problem based on first- or second-hand evidence-based knowledge.

Jose Puppim

Jose Antonio Puppim de Oliveira is Assistant Director and Senior Research Fellow at the United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies (UNU-IAS).

Urban planning in many countries is a profession, so planning researchers work closely with practitioners. Indeed, the questions posed by this roundtable are objects of research in planning. The issue is broader than knowledge generation, but encompasses knowledge use and acceptance of knowledge. Knowledge in the urban planning context is embedded in the political, social, and cultural context. This is particularly relevant when knowledge is applied in practice and has economic and political implications.

For example, if a new road is been proposed, there are many ways the road could be designed (different routes, different widths, etc.), and each design will have a social, political, and economic implication. For instance, if the road is close to my house, it will increase the value of my house, but if it is too close, it may be a disturbance. Thus scientific and technical knowledge can help the decisions, but the final decisions in the urban context will be a political decision. There is no "definitive truth" or "neutral knowledge" in urban planning, and that is why cities are so different.

As a scientist/researcher, I truly believe that research can advance practice. But I am critical about the use of scientific knowledge in certain instances, which many times is used to empower the powerful (who can buy and use the best knowledge and hire the best technical people) and disempower the powerless (in general, the poor or the weakest in society, such as minorities). Over-reliance on technical information and on the opinion of experts is occurring side by side with negligence of local knowledge and lack of effective public participation from non-technical, other actors in decision-making. This creates an imbalance in the political process and also a sense of overconfidence regarding scientific knowledge that can be dangerous in many instances. Thus, the right direction for good planning is to figure out how to balance the different kinds of knowledge to make better planning processes and outcomes.

The best way to increase and advance interactions between different kinds of knowledge is public participation, which is a political process. Even though public participation can be a means to inform, consult, involve, collaborate, or empower (citizens and scientists); it can also lead to manipulation, coercion, and misinformation. How participation is integrated into decision-making process determines the benefits for specific land use planning outcomes along with legitimacy and fairness of the process. However, there is still a lack of understanding and scarce empirical research done on how the participation of different actors can effectively affect public interventions in land use planning, particularly those promoted by government and developers. What we know is that there is no "right way" to do participation, and an interesting point of participatory/interactive processes is that the outcomes can be very different, even among the same group of stakeholders or with the same people.

Diane Pataki

Diane Pataki is an ecologist who studies the role of vegetation in the functioning of cities. She is currently a Professor in the Dept. of Biology at the University of Utah.

This topic is timely as I'm one of the many researchers who would like to do more to translate knowledge into action. Yet, the notion that progress has been slow and difficult is familiar. In addition to common concerns about communication and process, I see an additional barrier to the integration of science and practice.

Scientists are trained to be critical. We are constantly critiquing ideas, methods, and results. Critique comes in many forms: manuscript and proposal reviews, supervision of student work, and discussions of new projects and findings with colleagues. There are always alternative ways of looking at data, uncertainties in methods and extrapolations, and better ways of conducting experiments and observations. Critique and skepticism are the scientific habits of mind, and with good reason—this is one central way in which we advance scientific understanding.

However, cities can't be built on skepticism. To construct livable places, we have to envision, inspire, plan, design, and implement. We have to create instead of tearing down. Yet scientists are trained to continually challenge ideas, point out uncertainties, and highlight dubious assumptions. This must be done—there is an important role of examining uncertainties and assumptions of new ideas from a scientific perspective. But there is also a role for science that inspires. The opportunity to integrate scientific knowledge into a new vision for cities, one which translates our increasingly nuanced understanding of nature and human-environment interactions, has never been greater. How can we take advantage of these opportunities?

I have spoken with many practitioners and decision-makers in the cities in which I live and work. There is truly a desire to integrate good science into practice in these places. My research focuses on costs and benefits of different types of vegetation and landscaping in cities. There is wide consensus that re-vegetating cities has many benefits, as evidenced by many posts here and elsewhere. But "the devil is in the details." Currently, I see a dichotomy in how scientists and practitioners approach this issue. On the one hand, the call for "more green, everywhere" has swept through cities the world over. But the possible configurations for constructed greenspace are virtually endless. Our research has shown (not surprisingly) that these configurations matter—particular plant types, species, and spatial arrangements have a large influence on the outcomes for greenspace, both positive and negative. In many cities, the commonly cited option of restoring native plant assemblages to urban areas is not feasible or even desirable (in arid cities, for example, where trees and other culturally important vegetation is not native). Given the range of options, science can and should inform new greenspace designs, which could be monitored and evaluated with the wide array of instrumentation used to study non-urban ecosystems. But to date, there is still a wide gap between urban ecosystem science and practice.

One way to bridge the gap may be to focus on developing the collective vision of scientists, practitioners, and stakeholders about the cities in which they want to live. Beyond the experiments, the methods, and the data, scientists have a role to play in helping to shape a vision of the future in which our best understanding of place-based ecology, the built environment, and well-being are all integrated. Such visions can be aspirational—even unattainable. And they will change over time. The process of envisioning and working toward a common goal may be enough, even if the goal is later refuted by new information, or otherwise never fully realized.

Critiques have their place, but so does the process of developing a shared vision in which scientific advances are part of an exciting new future for cities and urban nature.

Bram Gunther

Bram Gunther is the Chief of Forestry, Horticulture, and Natural Resources for the NYC Parks Dept and the President of the Natural Areas Conservancy.

Bram Gunther, Eric Sanderson, and Sarah Charlop-Powers

"Never doubt that a group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it is the only thing that ever has." — attributed to Margaret Mead

This is a quote that could have come from a conversation over a beer. But now it's the adopted motto of a new initiative called NYC 2050 Nature Goals, designed to bring academics, public land managers, and the non-profit conservation community together in New York City. The Natural Areas Conservancy, a new voice in the urban conservation world, is leading this initiative in collaboration with the Wildlife Conservation Society, founded 120 years ago to conserve wildlife globally and teach about wildlife through urban zoological parks such as the Bronx Zoo and New York Aquarium.

NYC Nature Goals 2050 brings together people who work in over 25 different institutions and are invested in New York City urban conservation and ecological restoration. What makes this effort interesting is that (1) as a group we are focused on all resources within the city lines, from the estuary to the uplands, from the natural to the built, and from the public to the private; (2) we are not explicitly policy focused, but rather aspiration focused; and (3) at the first three workshops each individual is representing his or her own values. Only in the last workshop do we sync our individual values with our institutional missions. To this end, we will hope to write a "constitution" to facilitate alignment among groups in different spheres (research, government, NGO, community), so that our sum is greater than our pieces.

Our conversation about goals follows a trajectory from function to composition to structure (Redford and Richter 1999). Function is about what interactions we want from nature, answering the question: "why have nature in the city?"

We held a meeting on this topic in March and the five top consensus answers that emerged were:

- Biodiversity and habitat—NYC nature provides living environments for species

- Coastal protection/resilience—NYC nature mitigates damage from coastal storms

- Water quality—NYC nature absorbs and filters water from runoff

- Connectivity—NYC nature enables movements of species through the city

- Inspiration—NYC nature encourages humanity creativity and appreciation of beauty.

Composition focuses on what components of nature are necessary to fulfill the functions outlined, helping us articulate: "what nature in the city?" We just held a meeting on composition and are digesting the results now (native species as opposed to introduced ones were strongly endorsed, for example.)

Structure is perhaps the hardest of the three: it answers, "how much nature or in what configuration is it required to fulfill the functions outlined". Here we expect to come up against some difficult questions about nature in the city: how much salt marsh provides coastal protection? What configuration of nature assures connectivity for migratory birds? How large does a natural area need to be to inspire? We expect to generate a set of research questions tied to the nature goals of this kind.

At a fourth meeting, to be held in December, we will ask members of the advisory group to speak to the goals not as individuals, but as members of institutions.

In this initiative, we are making a space for individual values to be aligned ultimately with institutional values—this combination is a powerful force and hews to the Margaret Mead quote above. The driving goal of the NYC 2050 Nature Goals is to ask folks to think in a visionary way. This vision and the long-range aspirations for our City that we identify as a group will influence our short-range goals, capacity to coordinate efforts and initiatives, and decide our ultimate directions.

In our workshops, we're deliberately staying focused on the process rather than the outcomes per se, so that our ideas can fly above the usual and lead to places not envisioned before, drawn from and shared by researchers and practitioners.

If this conversation does spread to "bar" talk, the more the better.

Eric Sanderson

Eric Sanderson is a Senior Conservation Ecologist at the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the author of Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City.

Sarah Charlop-Powers

Sarah Charlop-Powers is the Executive Director of the Natural Areas Conservancy, with a background in land use planning, economics and environmental management.

Yvonne Lynch

Yvonne is an urban climate adaptation policy expert and communications strategist and leads the Urban Ecology and Urban Forest Team at the City of Melbourne.

If 10 scientists and 10 practitioners were walking into a bar, it's entirely possible that they would not be walking in together. As the benefits and value to be gained through scientist-practitioner collaborations remain largely untapped, the time has come for the confluence of these divergent communities, so I hope this bar has a late trading licence!

A key challenge for urban nature-focused scientists and practitioners is the ability to affect the process of urbanisation itself. We know that nature and green infrastructure in cities is still regarded primarily for its amenity value instead of its essential ecosystem services provision. Grey infrastructure and the built form command priority and investment in both city planning and market processes. You could say that we have a relatively simple formula for how we grow our cities, and that formula is: grey in, green out. With climate change looming and population growth booming, there is no doubt that we need to transition toward a new way of developing our cities and towns.

What we need is the rapid co-production of relevant knowledge that can inform and transform urban policy and practice. This requires that research and practitioner communities establish effective partnerships, engage in an ongoing dialogue, and formulate research questions together. Currently, scientists and academics have limited incentives to undertake research that is focused on practice because research is normally orientated towards other academics rather than practitioners. There is often an optimism that the research will make its way back to practice. More direct contact between scientists and practitioners would go some way to remedying this situation and it would dramatically improve both the quality of research and policy practice.

So why is there limited interaction between scientists and practitioners? At this stage, I've been to more conferences, seminars, and symposiums than I've had hot dinners. I've yet to see a beautiful blend of scientists and practitioners together in major conference programs. I think it's an area for improvement. Joint seminars and conferences between scientists and practitioners can help demonstrate the relevance of research to practitioners and the relevance of practitioners to researchers. It would definitely lead to more bar-time together.

Attendees in Melbourne at the National Urban Forest Master Class, 25 June 2015.

On 25 June, the City of Melbourne convened a National Urban Forest Master Class with the Victorian State Government and the 202020 Vision to advance planning and implementation of urban greening across Australia. We brought together over 200 local government officers, practitioners and researchers and provided them with a "How to Grow an Urban Forest" guidebook. The most important aspects of the Master Class for the practitioners were the focus sessions on demystifying the data and the science, communication, and effective partnership development. For the researchers and scientists, the critical component was an insight into the political and community contexts that frame policy development.

Neil Brenner's work demonstrates urbanization is a process of constant transformation that leads continuously to the production of new urban configurations and constellations. We need to collaborate to understand that. Cities are the ideal canvas for research and we've never had more at stake in terms of how we're developing. The deliberation at the bar needs to focus on how we can advance our ability to understand and solve complex problems together, how we can develop a shared understanding of our similarities, and, ultimately, how we can focus the lens on reality and combine intellect and resources to advance the outcomes for urban nature.

Myla Aronson

Myla Aronson is an urban ecologist at Rutgers University, NJ. Her research focuses on the patterns and drivers of biodiversity of cities to better conserve, restore, and manage biodiversity in cities.

Urban ecologists are looking for their research on the ecology of cities to be applied to conservation and management of biodiversity in cities. Practitioners are looking to urban ecologists to help bridge research findings into practical applications of day-to-day management. But how do we bridge the gap between scientists and practitioners?

Communication, data sharing, and collaborative research are key to bridging this gap. Communication can be enhanced through data sharing and collaborative research, but also through initiatives such as The Nature of Cities and UrBioNet. My colleagues and I recently established UrBioNet: A global network for urban biodiversity research and practice, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation. UrBioNet has been established to develop a network that brings together researchers, practitioners, and students with an interest in biodiversity in cities. The network provides a forum for discussion, data sharing, and collaboration on topics relevant to urban biodiversity research, management, design, and planning. Communication between scientists and practitioners can also be achieved with college level ecology courses that incorporate project based learning through internships or projects with practitioners.

Practitioners have treasure troves of data. This data spans from hard numbers on endangered species populations to knowledge from trial and error on restoration practice. Rarely do managers have opportunities to synthesize these data and knowledge. Data offer an avenue for knowledge transfer and collaboration between scientists and practitioners. Sharing data across cities, countries, and continents has allowed us to better understand the role cities play in biodiversity conservation (for example, see Aronson et al. 2014). At the local level, sharing data will allow us, together, to develop best management practices for biodiversity.

Ecological research in urban areas is inherently collaborative. However, we need more opportunities to bring together scientists and practitioners. Better mechanisms for funding of research, better facilitation for scientists to perform their research in cities (i.e., less red tape), and research that incorporates practitioner experience and knowledge are all needed. Collaborative research efforts such as the Center for Resilient Landscapes, which combines academic scientists and students with practitioners at Rutgers University, USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, and the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, are starting points for successful collaborative research.

Incredibly, we don't even know the full biodiversity of cities. Recent research in cities has shown that cities house a surprisingly high diversity of species. At the global scale, cities house over 20 percent of the world's bird species (Aronson et al. 2014). The discovery of new species is no longer confined to far-off, exotic places such as the Amazon Basin. In New York City, Jeremy Feinberg, a graduate student at Rutgers University, recently discovered a species of frog, hidden cryptically on Staten Island, and never described before, despite the long history of natural sciences in New York City (Feinberg et al. 2014). In Los Angeles, Emily Hartop and colleagues at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles discovered 30 new species of flies in urban backyards (Hartop et al. 2015).

Despite these new and exciting discoveries and the explosion of research by natural and social scientists in cities, we still have a limited understanding of how biodiversity—the plants, animals, insects, fungi, and even soil bacteria—function in urban habitats and how we can effectively conserve and manage biodiversity in these landscapes that have been designed and managed for humans.

So, when scientists and practitioners and get together, what do we talk about? We talk about how we can work together effectively to conserve and manage biodiversity in our cities. We ask big questions: How can we manage habitats in cities at multiple spatial scales? How can we use the data we have to create targets/thresholds for urban management? What are realistic goals for invasive species management? What are the best management practices for restoration of native habitats? What are the factors important to measure for monitoring urban forests? What tools can we use to communicate and synthesize management/restoration findings?

We may have more questions than answers, but we are communicating, and this is the start for successful biodiversity conservation and management in our world's cities.

References

Aronson, M.F.J., F.A. La Sorte, C.H. Nilon., et al. 2014 A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 281: 20133330.

Hartop, E.A., B.V. Brown, and R.H.L. Disney. 2015. Opportunity in our Ignorance: Urban Biodiversity Study Reveals 30 New Species and One New Nearctic Record for Megaselia (Diptera: Phoridae) in Los Angeles (California, USA). Zootaxa 3941: 451-484.

Feinberg, J.A., C.E. Newman, G.J. Watkins-Colwell, M.D. Schlesinger, B. Zarate, B.R. Curry, H.B. Shaffer, and J. Burger. 2014. Cryptic Diversity in Metropolis: Confirmation of a New Leopard Frog Species (Anura: Ranidae) from New York City and Surrounding Atlantic Coast Regions. PLOS One: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108213.

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course onconserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and he has recently published a book titled, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

I can imagine a conversation about urban development between scientists and practitioners sipping on their favorite beverages would go something like this:

Practitioners: When designing a site for development, there are many constraints that basically boil down to time and money. Conserving open space here and there means less buildable space. Even conserving vegetation on lots and between lots and saving individual trees and small patches of trees, buffers, and soils takes effort and planning. Where should our efforts be placed to retain biodiversity and minimize impacts? When moving a road or adjusting the location and size of built and conserved spaces, can we quickly evaluate the impacts on different species? We need to balance the developers' needs and economic realities with biodiversity concerns, so we need rapid assessments of the biodiversity value of different designs.