Bogotá, Colombia's Tranmilenio: How Public Transportation Can Socially Include and Socially Exclude

Public transportation can simultaneously better integrate certain groups of people into the urban framework as well as exclude other groups of people. The degree of mobility people can access in a city can be directly influenced by the accessibility of its public transportation system (Morales, 2010, 7). I feel that effective urban planning involves working to make sure that all social groups are able to access public transportation and move freely place to place . In order to understand the idea of "people's right to mobility" more deeply, I researched Bogotá, Colombia's bus rapid transit (BRT) system Transmilenio. I synthesized an array of information on the subject, and I feel that in order for Transmilenio to continue to become a more effective tool for social inclusion, emergent issues such as its linkage with the traditional bus system and its public image need to be addressed.

How Transmilenio Socially Includes:

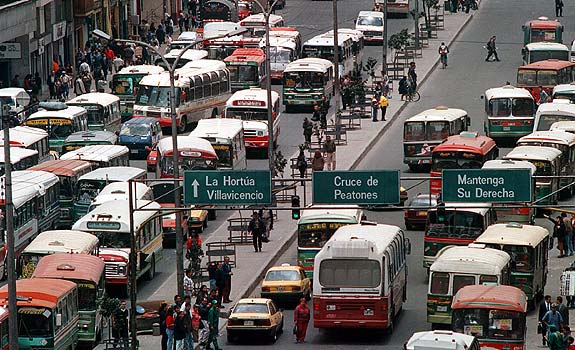

- Transmilenio reduced the "war of the centavo" which caused congestion and decreased the safety of the streets. Many times drivers would race each other and stop at undesignated bus stops. According to Duarte (2012), it was reported that due to this system of small, independent bus companies, there were more than 20,000 buses and minibuses (4). Traffic congestion hindered the ability of people to effectively move place to place, and the average vehicle speed was between 12 km/h and 18 km/h (Duarte, 2012, 4).

- Transmilenio will eventually cover 80% of urban transport needs of the city using 386.6 kilometers of corridor routes (Gilbert, 2008, 442). Currently the system is operating on 84 kilometers of corridor routes (Phase I and II) with 1,029 articulated buses. Each articulated bus can carry approximately 160 passengers, 112 standing and the rest sitting (Gilbert, 2008, 442). Although there is risk of delay when a system is not built at the same time, when a system is developed in stages it still allows for the system to be used even if it is unfinished (Lleras, 2003, 28).

- Red articulated buses or the main trunk mode operate along designated bus routes, while the feeder buses travel to residential areas (many are poor areas) and connect to the main stations (Gilbert, 2008, 442; Morales, 14). This enables members of the community that need affordable public transportation the most to reach the city center and have more reliable opportunities for mobility.

- It is easier to physically travel to Transmilenio stations since the stations can be reached by multiple modes of transport such as pedestrian bridges and bicycle. A study conducted by Duarte and Rojas (2012) determined that all terminals in Bogotá have good pedestrian access due to the abundance in crosswalk and traffic lights at all entrances (10). This trend seems to illustrate a growing awareness of how important it is to spatially orient stations to neighborhoods so that people can easily walk to these services.

How Transmileno Socially Excludes:

- Tranmilenio's relationship with the traditional bus system is highly competitive which still indireclty causes overcrowding and a lack of organization. Some of the specific issues arising from competition between bus systems is fuel subsidy discrepancies, and Transmilieno purchasing buses from the old system slower than expected.

- Transmilenio is still running on the same 84 kilometers of route, which can contribute to delays as well as overcrowding of the existing buses. Phase III of the system is currently 1.5 years behind schedule (Hutchinson, 2011). By default, many groups of people are excluded from the system simply because the system is not located in their neighborhood at present.

- In the southeast of the city, the terrain is quite mountainous and people rely on the feeder service instead of the main routes. This creates a time-space conflict as people become spatially segregated or unable to move from place to place efficiently.

- Another time-space conflict is how the BRT system does not provide accessible transport through the night which can be essential, especially in poor neighborhoods where people may not have access to private vehicles (Morales, 2010, 23).

- Both stations and buses require more maps so that users can better spatially orient themselves station to station. Even though stations depict well-made maps detailing stations and routes, the stations, which are typically three city blocks long, require more signs and maps.

Discussion:

Understanding the possible duality between social inclusion and social exclusion is an important aspect in the discipline of sustainable urban planning. The "right to mobility" is important to consider because mobility allows people to move place to place and connect with each other on a greater level. If mobility is not easily accessed, especially if it is only certain groups that are experiencing the difficulty, this can create exclusion and tensions among social groups. Competent and extensive public transportation is also important because ultimately it is the public that will either cause a planning objective to thrive or deteriorate. I feel that two of the most significant obstacles Transmilenio faces are its public image and relationship with the traditional bus system.

Although there has been talk of a metro and criticism that the system has not been funded, it is important to consider the long-term usefulness of Transmilenio. According to Hutchinson (2011), a metro system would only cover 8% of the city, while the BRT system is supposed to cover 80% of the city. The idea of "metro envy" is, therefore, important to consider. Perhaps a metro would be useful for Bogotá, but perhaps if Tranmilenio was already completed there would be less of a focus or need for a metro. It seems that with every delay, Transmilenio's dependability and public image suffers.

Another question that remains is how can the traditional be integrated into Transmilenio most effectively, reducing the competition between the two systems? The traditional bus system it provides important employment to many people within the city and reaches that Transmilenio cannot reach yet.

I feel that there seems to be many questions that need to be addressed in order for Transmilenio to move forward successfully. However, I do not think the uncertainty that surrounds Transmilenio is necessarily negative. Transmilenio was a hugely influential planning initiative Bogotá implemented. It makes sense that there would inevitably be many emerging issues that go hand-in-hand when a new project of Transmilenio's magnitude is initiated. Questions that I still have about Transmilenio center around two ideas: How can residents become better integrated into the planning process? What will it take for Transmilenio to be completed more quickly?

References Cited:

Ardila, A. 2007. How public transportation's past is haunting its future in Bogota, Colombia. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2038. 1-15.

Duarte, F. and Rojas, F. 2012. Intermodal connectivity to BRT: a comparative analysis of Bogota and Curitiba. Journal of Public Transportation. 15: 2. 1-18.

Gilbert, A. Bus rapid transit: is Transmilenio a miracle cure? 2008. Transport Reviews. 28:4. 439-467.

Hutchinson, A. 14, July 2011. TransMilenio: the good, the bus, and the ugly. The City Fix. Available through http://thecityfix.com/blog/transmilenio-the-good-the-bus-and-the-ugly/

* Hutchinson also showcases a short video with footage on how Transmilenio works.

Lleras, G. C. 2003. Bus rapid transit: impacts on travel behavior in Bogota. Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Morales, E. B. 2010. Promoting the right to the city through a transport system? The case of Transmilenio, the BRT of Bogota. Development Planning Unit University of College London. 1-36.