Can Ontario deliver the continent's best land-use plan?

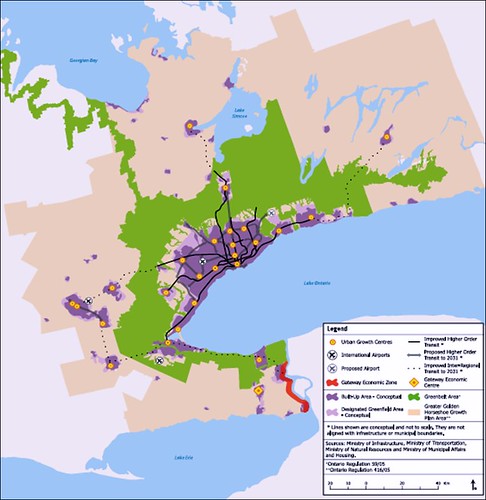

I'm fond of saying that the best-conceived plan for managing growth and development in North America is the Places to Grow framework adopted by the province of Ontario, Canada. Constructed pursuant to enabling legislation adopted by the province in 2005, Places to Grow addresses the future of a New Hampshire-sized region around and including Toronto, Canada's largest city, and Hamilton, its 8th-largest. Called the "Greater Golden Horseshoe" for its bending shape around the western edge of Lake Ontario, the region also touches Lake Erie and the Georgian Bay that extends from Lake Huron.

I was fortunate enough to be invited to participate in some of the planning sessions for Places to Grow, and in 2007 I wrote that it was the best land-use plan I have ever seen. I'm still not sure that I have seen a better one, at least in concept: the plan, if fully implemented, will channel growth to the places within the Horseshoe region where environmental impacts will be reduced compared to an unmanaged scenario, as well as to places, including distressed inner city neighborhoods, that would benefit from more investment, jobs and people.

The Horseshoe region is forecast to grow by 3.7 million people (a 47 percent population increase) and 1.8 million jobs by 2031. It is already home to a quarter of Canada's population and will soon be the third-largest urban region in North America. Imagine the consequences if development is allowed to spread all over the land, without good planning. Imagine the lost landscape, the additional roads and traffic, the pollution, the lost habitat, the global warming emissions.

The basics of Places to Grow

Here's how Places to Grow (full, updated text here) seeks to prevent that from happening:

- By 2015, a minimum of 40 percent of new residential growth in each municipality must occur not on what is now forest or farmland but within existing cities and towns, via such measures as building on vacant parcels, converting brownfields and grayfields to new uses, and redeveloping obsolete properties.

- The plan places special emphasis on downtowns, transit corridors, and "major transit station areas." Downtown areas, in particular, must strive to accommodate about 90 residents and/or jobs per acre by 2031, with highly urban Toronto's target set at twice that amount.

- The plan recognizes that not all growth can occur in existing communities, and municipalities may also go through a process to designate greenfield areas for development. But greenfield development, when it occurs, must create complete communities, with development configurations and streets that support transit services, walking, biking, parks, and a mix of housing and jobs. And it must be built to a scale that makes efficient use of land, accommodating a minimum of about 20 residents and jobs per acre.

- All growth areas must accommodate affordable housing.

- Development generally may not occur outside of the designated areas. Areas important to natural resources or the environment must be protected, and there are restrictions on development of prime farmland.

To support the plan, the government hopes to provide substantial public transit investments and other necessary infrastructure over five years.

Perhaps most visibly, the new plan will allow the continued protection of a greenbelt comprising 1.8 million acres of rural and conservation land, an area over three times the size of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the US, and just a shade smaller than Yellowstone National Park. On the large map accompanying this post, the green area is the greenbelt and related protected land; the purple areas are urbanized zones, including Toronto and its suburbs; the lines represent existing and planned major transit; and the beige area defines the limits of the planning region.

Best of all, Places to Grow has the full force and effect of law, thanks to Ontario's Places to Grow Act of 2005. That law requires that local planning decisions, including zoning, conform to the policies in the regional plan. If there is a discrepancy, the provincial government has the authority to amend municipal decisions.

Stumbling blocks

To say that this undertaking took massive amounts of time, process, cooperation, understanding, and political will is a gross understatement. It's a remarkable achievement unequalled by anything similar to date in the US. But how does it all look now, a few years down the road since the plan's 2006 adoption?

It's a 25-year plan, of course, and it's way soon to tell what the final outcome will be. But some pieces are falling into place. For starters, the Ontario Growth Secretariat reports a high degree of municipal compliance:

"There are 21 upper- or single-tier municipalities and 89 lower-tier municipalities in the Greater Golden Horseshoe. All of them have undertaken work to implement the Growth Plan since its release in 2006.

"All 19 upper- and single-tier municipalities with official plans have adopted amendments to conform to the Growth Plan. These are currently in effect or in the approvals process. Two of the upper-tier municipalities - the County of Dufferin and the County of Northumberland - do not have official plans. Both, however, have completed growth management strategies to provide guidance to area municipalities.

"Nearly half of the lower-tier municipalities in the Greater Golden Horseshoe have adopted an official plan amendment to conform to the Growth Plan."

That said, some regional environmentalists have been distinctly unhappy - not with the provincial goverment, but with a failure on the part of some municipalities to implement Places to Grow in good faith. In a scathing 2009 report (three years into the 25-year implementation period) titled Places to Sprawl, the Ontario Greenbelt Alliance charged that four of the 21 upper-tier (basically, county-level) municipalities had "passed, or drafted, official plan amendments that contain growth strategies that directly contradict the intent and spirit of the Places to Grow Act."

The sharpest criticisms were directed at the Durham region, which, according to a local Sierra Club leader's statement in a press release, "completely disregarded" the planning law and overestimated job growth projections "to justify the destruction of prime agricultural land and environmentally significant areas." That's a pretty sharp accusation. A separate Sierra Club statement noted that the Durham region was the only municipality to formally oppose the creation of the Ontario Greenbelt. The report also charged Niagara Region, York Region, and Simcoe County with serious implementation shortcomings. (It also found some municipalities to praise.)

An editorial published last week in the Toronto Star criticized municipalities in the region for a different problem, inconsitent compliance with the plan's direction that existing communities absorb a fair share of new development. The article called for the province to tighten the rules to limit local discretion so that the intent of the law and plan could be realized.

But a lot of progress, too

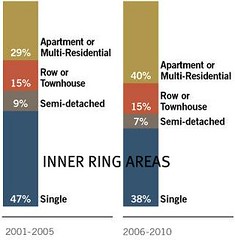

More optimistically, the Ontario Growth Secretariat has reported that the mix of housing types in the region is already shifting to a denser form that will consume less land, shorten driving trips, and promote more walkability and transit use. In particular, in the five years immediately prior to plan adoption, the share of multifamily and attached housing starts in Toronto, Hamilton, Oshawa and their inner suburbs was 53 percent; in the five years since adoption, the share has increased to 62 percent. The share of detached, single-family housing starts has declined from 47 to 38 percent. Even in the outer parts of the region, the share of multifamily and attached housing starts has risen from 29 to 41 percent after the plan's adoption,

The protests of the Star notwithstanding, of the 63,000 new residential units that were added to the Greater Golden Horseshoe between June 2009 and June 2010, approximately 44,300 - or 70 percent - were located within the existing development footprint.

An article written by Vince Versace and published last summer in the Daily Commercial News and Construction Record summarized a number of significant construction projects that have taken place in designated urban centers since the plan's adoption:

"[The plan's] directive for downtown growth has resulted in numerous construction projects such as Oshawa's new consolidated courthouse, the downtown campus for the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, a YMCA facility and the GM Centre arena and entertainment venue.

"In downtown Kitchener, construction of a new Health Sciences Campus of the University of Waterloo was completed and the Waterloo Region Consolidated Courthouse is under construction.

"The plan has also helped drive investments in cultural, recreational and civic infrastructure to help "create vital, mixed-use downtown communities". Construction resulted across Golden Horseshoe communities such as the Pickering Recreation Complex, Brantford Civic Centre, Mississauga Civic Centre public square, Peel Heritage Complex restoration, Peterborough Market Hall restoration and Brock University's School of the Performing Arts in St. Catharines.

"Provincial investment in urban growth-geared projects ranged from $1 million for Brantford's Civic Centre to $379 million for Kitchener's Waterloo Region Consolidated Courthouse.

"Other projects to receive provincial funding were Hamilton's Lister Block receiving $7 million and Toronto's Ryerson Student Learning centre which received $45 million."

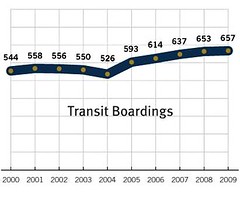

The progress on transit is also impressive: the Secretariat reports that, according to data collected by the Canadian Urban Transit Association, the annual number of passenger trips taken by transit in the Greater Golden Horseshoe has grown steadily from 526 million trips in 2004 to 657 million trips in 2009. In addition, approximately $8.6 billion has been invested since 2006 in public transit across Ontario, including $4.1 billion in GO Transit (which serves the Toronto and Hamilton metro areas).

In addition, in 2006, the Province established an entity called Metrolinx to coordinate transportation planning and operations across the greater Toronto and Hamilton Area and as a mechanism to implement the growth plan. In 2008, Metrolinx released a regional transportation plan called The Big Move, a sort of transportation companion to Places to Grow. The Big Move outlines a $50 billion long-range strategy to guide transportation planning and investments across the region.

Aspirations and expectations

These are impressive achievements and impressive numbers, and there is every reason to think that they will continue to get better. Recall that population is expected to grow by 47 percent over the 25-year planning period. The provincial government projects that, under Places to Grow, the increase in developed land across the Horseshoe during that time will be only 14 percent, instead of 39 percent without the plan; and that the average density of development across the region will increase by 20 percent, instead of declining by 2 percent as it would without the plan.

With plans as ambitious as this one - and it really has no equal in the US - some problems with implementation are inevitable. Indeed, if there were none, I might suggest that the province's goals were too modest. But at least the citizens and advocates of the Horseshoe region can argue about whether goals are being met: that's a much better debate to have than whether there should be any legally meaningful goals at all. And at some point the enforcement mechanisms available to the province can come into play.

I'm not going to go out on a limb and say that I expect everything about Places to Grow to be perfect, or that continued support and vigilance by environmental interests won't continue to be absolutely necessary. But I can think of about a hundred regions south of the Canadian border, including the one I live in, that I fervently wish were attempting something this good.

(Notes: In March of last year, a second Places to Grow plan was initiated, this one for northern Ontario. "A Place to Stand, a Place to Grow" is the title of a much-loved song that became a sort of unofficial anthem for Ontario.)

Kaid Benfield writes (almost) daily about community, development, and the environment. For more posts, see his blog's home page. Please also visit NRDC's sustainable communities video channel.