Cincinnati Light Rail Triumphs Over Bizarro Opposition

This time it's real. Cincinnati voters have (again) defeated a misguided attempt to block the city's new streetcar, which now will move forward and could be operational as early as 2013.

As I have written before, the Cincinnati streetcar will link the city's two most significant job centers, downtown and the uptown district around the University of Cincinnati. Even better, the streetcar will serve and help renew the wonderful historic district of Over-the-Rhine, which only a decade ago had fallen into such serious disinvestment and abandonment that 90 percent of its properties had become vacant and at least one survey called it the most dangerous neighborhood in America. (The "most dangerous" claim was convincingly rebutted here.)

But highly walkable and adjacent to downtown with buildings ripe for adaptive reuse, Over-the-Rhine is perfectly poised to become an exceptional example of restoration and redevelopment with a small environmental footprint. It is also a preservationist's dream, containing the nation's most impressive inventory of 19th-century Italianate architecture, along with the city's magnificent old Music Hall,

The streetcar will help tremendously. It will not only be a sustainable form of transportation to jobs and amenities but also attract investment near its stops, because of the permanence of its fixed route. One would think this would be a no-brainer. Kevin Osborne summarized the case for the streetcar in the local Cincinnati outlet CityBeat:

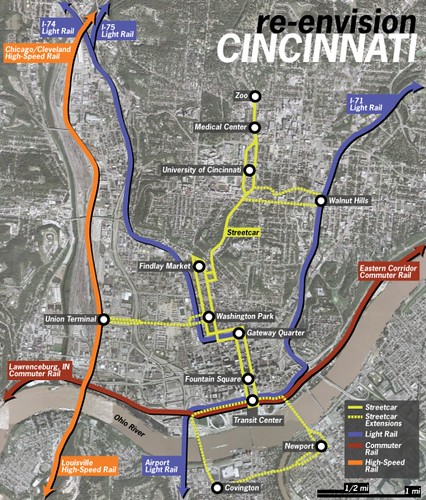

"Streetcar supporters say the project's primary purpose is as an economic development tool, spurring investment in vacant and dilapidated properties along its route. Cincinnati's proposed 3.1-mile loop would travel from downtown's Government Square north through Over-the-Rhine to Findlay Market. If successful, it likely would be expanded later into other areas including the uptown area near the University of Cincinnati.

"Studies have indicated the local streetcar system would spark nearly $1.4 billion in new development on vacant and dilapidated properties along its route. That means it would produce – when adjusted in today's value — up to $2.70 in economic activity for every $1 invested."

This is entirely consistent with research and experience in other cities.

And yet the Cincinnati plan became highly controversial, due to anti-government and anti-spending sentiment, a belief by some that the city wasn't doing

Kevin Osborne's article described the ballot measure this way:

"If it had been approved, Issue 48 would have prohibited city officials from spending money on anything related to preparing any type of passenger rail transit, including the streetcar system, through Dec. 31, 2020. Further, it would've restricted the city from accepting federal grants for such projects, along with entering into public-private partnerships or even accepting private investment for a passenger rail project within the city's rights-of-way."

That's really severe and wildly out of sync with much of the country. (The author of Issue 48 has apparently been fighting progressive causes for some time. Jake Mecklenborg reports in UrbanCincy that he also authored a notorious anti-LGBT amendment to the city charter back in 1993.)

Concurrently with their rejection of the anti-streetcar measure, Cincinnati voters also apparently elected younger and more progressive city council members, strengthening council support for the streetcar. Construction could begin early next year.

Here's a one-minute video on the streetcar produced by the Cincinnati city government:

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.