Can Big Data Deliver Evidence Based Urban Design?

The following article is modified from a presentation prepared for the National AIA Convention 2015 in Atlanta on May 14, titled: "Smart Cities and Innovation: Resilience, Adaptation, and Eco Districts"

Cities now represent the core hubs of the global economy, acting as hives of innovation in technical, financial and other services. (A quote from a 2011 brochure titled "the new economics of Cities")

Cities and metro regions have become the dominant human life-form, Cities are considered nimbler, easier to govern and therefore more innovative than states and countries. Many Cities have become the drivers in sustainability, in resilience, in local food production and in alternative transport.

Increasingly mayors collaborate across continents such as in the Global Cities Initiative, a five-year project that aims to help leaders in U.S. metropolitan areas reorient their economies toward greater engagement in world markets.

Is big data nothing but a quest for another utopia?

In this context it is obvious that urban design has to step up its game. Of what help can digital technology be?

No longer can the model be the "Collage City" as architectural historian Collin Rowe had called it, an artful juxtaposition of fragments. It can't be merely self organization as Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas has occasionally propagated it in his reporting from Lagos. Certainly, it won't do any longer to represent cities with analog wood models.

Can big data, open data, and real- time measurements of everything get us to such a thing as "evidence based urban design", fact-based city planning, and an approach that thinks long-term instead of in election cycles? In other words, can Smart Cities technology, i.e. the transition from analog to digital, bring about a more holistic, system-based and scientific approach to city planning? In light of the lopsided wealth patterns of US cities, the question also becomes: Can a more scientific, data based approach address issues of equity?

The answers vary depending on whom one asks. Big business, regular citizens, or professionals. The views range from dream to nightmare.

The topic of the digital city promises to be big business, so big business such as GE or Siemens are hot on the topic and promote proliferation of the digital city on many levels.

On the other end of the spectrum but equally optimistic is researcher and urban planner Anthony Townsend who wrote the book "Smart Cities", Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a new Utopia". He looks at the base, i.e. where the people are and sees empowerment from enhanced communication, coordination and the effects of what is known as "crowd sourcing". He writes:

The economic impact of mobile phones has been transformative for the world's urban poor. The [World] Bank's chief economist, Christine Zhen-Wei Qiang, argues that "Mobile phones have made a bigger difference to the lives of more people, more quickly, than any previous technology. They have spread the fastest and have become the single most transformative tool for development." With the basic infrastructure of smartphones and mobile broadband in place, there has been an explosion in services aimed at the poor. Several innovation hot spots have emerged where start-ups are translating business ideas born on the desktop Web of the rich world into SMS-based services for megacities' poor.

Finally, from the perspective of architects, urban designers and planners and considering the tools with which architects work in building design, digital technology has transformed the profession for some time. In the process one can probably say work has become more data based and "scientific" in the journey from hand drafting to computer aided design (CAD) to building information modeling (BIM). Graphic information of buildings now carries embedded data about the structure, systems, components and materials just as GIS carries data in maps for planners.

Thus, the expansion from building information modeling to the urban and regional scale seems not only logical, practical and inevitable, it is fully underway.

Cities responded with district designations as has been the practice for some time. There were urban renewal districts, empowerment zones, enterprise zones and much more, each a reaction to a newly discovered need.

So now we have the popular designations as Innovation and Eco Districts which represent the leap from the intelligent building to the smart district. New York's former mayor Bloomberg made the digital city a respectable and high priority affair with sustainability and resilience giving pretext and guidance for what kind of intelligence would be needed or desirable.

Example of interconnected systems manifest in a proposed Atlanta transportation center

Increasing congestion inefficiencies also demanded intelligence for larger geographic areas and systems towards comprehensive transportation and mobility strategies. Even the fashionable concept of "complete street" is much more complex than simple road capacity algorithms used to be with its aims for a multimodal and multi dimensional system rather than the one- dimensional metrics of "level of service".

In each of these examples the emphasis is on the system and its performance. In systems the results of certain actions tend to ripple in an interconnected way through many levels just like it is known from biology and physics. In human intervention this brings about intended and unintended consequences.

Cities are very complex systems, whether we speak of sustainability, resilience or transportation, each much too complicated to be understood intuitively. City systems are also too important to be controlled simply from a gut level.

It comes handy, then, that available technology allows not only the study of systems of increasing complexity but a design for optimization and reduction of the seemingly inevitable "unintended consequences". One way to do that is the development of virtual scenarios in which consequences and outcomes are made visible through simulation.

How does data-based planning affect urban design? Does the talk of Smart Cities, Innovation and Eco Districts make any difference to our profession or are these just fancy terms that come and go?

Let me answer this by way of two quite different anecdotal experiences:

Last year I participated in the jury for AIA's national urban design awards. 16 of 37 entries addressed large scale systems such as water or transport with resilience, sustainability, equity and choice in mind or they went for innovation districts as models for those systems. Entries ranged across the globe, the US, South America, Australia and most frequently, China.

Especially the entries for China opened the eyes for the scale of urbanization and the scale in which systems either work or fail and also the scale in which urban designers increasingly operate. Over 40% of the entries in urban design were devoted to the exploration of complex systems such as water, transport, energy and resilience. That is remarkable and an indicator of the shifts in our profession!

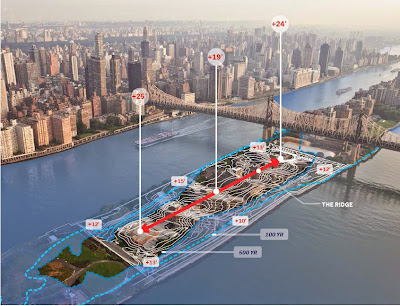

Roosevelt Island NY sea-level rise resiliency

If this example is in any way representative, we see a shift away from a mere aesthetic discussion of city as a desirable place in terms of form to a deeper consideration of a city where form is an expression of the systems that pulse through the physical form and its geographic manifestation.

The other anecdote comes from an ULI Advisory Service to which I was invited earlier this year. The task was to look at a Floridian resort island and help them to strategize a number of the usual planning issues that hit areas in high demand such as congestion and loss of open spaces. However, the problem manifest did not include anything about resilience which was kind of curious for a barrier island on the Gulf Coast.

From this second example one could deduce that the awards entrants were ahead of typical local planning reality. Given the real and imminent danger of rising sea-levels to the Florida coast, one could also say in that case traditional planning lags behind the real world.

I would conclude that the traditional approach to planning and urban design is rapidly becoming obsolete for a great number of reasons, with the need for resilience, sustainability and adaptability top along with equity and social justice.

To get a handle on these complicated system questions which were not usually seen as part of traditional urban design, data collection, processing, visualization, simulation and adaptation have become absolutely necessary.

The following examples of a data based design approach are somewhat simplistic and meant to illustrate an increase in scale from the building to the city and region and meant to be illustrative of what "digital city" can mean:

It comes handy, then, that available technology allows not only the study of systems of increasing complexity but a design for optimization and reduction of the seemingly inevitable "unintended consequences". One way to do that is the development of virtual scenarios in which consequences and outcomes are made visible through simulation.

How does data-based planning affect urban design? Does the talk of Smart Cities, Innovation and Eco Districts make any difference to our profession or are these just fancy terms that come and go?

Let me answer this by way of two quite different anecdotal experiences:

Last year I participated in the jury for AIA's national urban design awards. 16 of 37 entries addressed large scale systems such as water or transport with resilience, sustainability, equity and choice in mind or they went for innovation districts as models for those systems. Entries ranged across the globe, the US, South America, Australia and most frequently, China. Especially the entries for China opened the eyes for the scale of urbanization and the scale in which systems either work or fail and also the scale in which urban designers increasingly operate. Over 40% of the entries in urban design were devoted to the exploration of complex systems such as water, transport, energy and resilience. That is remarkable and an indicator of the shifts in our profession!

If this example is in any way representative, we see a shift away from a mere aesthetic discussion of city as a desirable place in terms of form to a deeper consideration of a city where form is an expression of the systems that pulse through the physical form and its geographic manifestation.

The other anecdote comes from an ULI Advisory Service to which I was invited earlier this year. The task was to look at a Floridian resort island and help them to strategize a number of the usual planning issues that hit areas in high demand such as congestion and loss of open spaces. However, the problem manifest did not include anything about resilience which was kind of curious for a barrier island on the Gulf Coast.

From this second example one could deduce that the awards entrants were ahead of typical local planning reality. Given the real and imminent danger of rising sea-levels to the Florida coast, one could also say in that case traditional planning lags behind the real world.

I would conclude that the traditional approach to planning and urban design is rapidly becoming obsolete for a great number of reasons, with the need for resilience, sustainability and adaptability top along with equity and social justice.

To get a handle on these complicated system questions which were not usually seen as part of traditional urban design, data collection, processing, visualization, simulation and adaptation have become absolutely necessary.

The following examples of a data based design approach are somewhat simplistic and meant to illustrate an increase in scale from the building to the city and region and meant to be illustrative of what "digital city" can mean:

This diagram increases the complexity by trying to indicate the metrics of urban systems and their relationships. Measuring metrics of interconnected systems is mostly still aspirational. Source: Nesta.

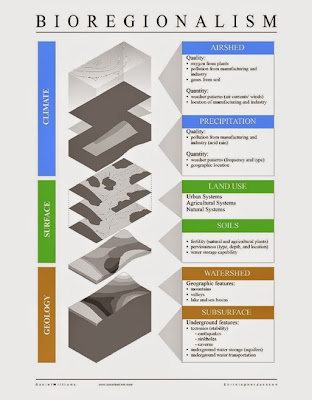

A somewhat speculative attempt of defining the region as a bio region with systems that include climate, topography and geology.

I hope to have laid out the range of issues from an urban design perspective. The use of big data and technology for urban and regional planning is by no means only for geeks. It is a question that goes to the heart of understanding how cities actually work and how they should work.

The transportation examples, specifically on congestion, may be the easiest to understand because many deal with these matters on a daily basis wishing better data can avoid congestion. Everybody knows already one pretty complex case of big data and its daily application: the Google maps that not only show real time traffic congestion and trip times but also dynamically guide the driver to the faster routes.

Sophisticated modeling already goes to the next step by not only showing real time present data but future data like a weather forecast. Predictions, i.e. traffic forecasts that tell you where traffic back-ups will form tomorrow are the new frontier.

Similarly we are finally able to not model ridership forecasts for planned transit systems but through open data also the commute sheds for various planned boarding points, i.e. how far can get via transit in half an hour and how many jobs are in this transit-shed.

With scarce public dollars it becomes ever more relevant to see how real time data management can help to optimize existing transit assets so they run on time and optimize transfers? Such an optimization of already operating transit systems can easily outperform investments in additional lines, trains, and buses. This should make smart city and real time data interesting to friends of investment and believers in austerity alike since digital tools can help to optimally design the new as well as achieve efficiencies and save money on what is already on the ground.

Criminologists are trying through data analysis to find out where crime will occur next. Looking at a city as a system has brought about the insight that some crime spreads much like a virus and that crime containment may have parallels with immunization campaigns.

Ratcheting complexity a few notches up we would be modeling a future that describes not only climate change and its effects but models its impacts and allows models of adaptation.

In short, from the perspective of local and regional planning, Innovation and Eco Districts are the petri dishes for new technologies and innovation modeling. But from the perspective of residents, the vision of a digital city cannot avoid to speak about governance, control and people.

We're gearing up for [..] the next vision of smart cities. What I was trying to do with the book [Smart Cities} was take that tiny little pinhole-sized view of the future that we were getting from corporate marketing, blow it up, and tie it to broader debates about the nature of urbanization. (Townsend)

Townsend's examples of cell phones as computing power in the hands of the masses gives rise to the hope that the technology represents not only an opportunity for traditional planning and the usual powers associated with it but an opportunity for potentially disruptive and explosive change.

Without proper controls and in the wrong hands, the digital city can easily become a horror of intrusion, dominance and oppression with knowledge in the hands of a few, a nightmare.

The dream of shared knowledge, increased access, more collaboration, best solutions rising to the top based on data and facts ultimately is a dream that doesn't depend on or come from technology alone.

But technology has opened a door and it behooves the profession of planners, architects and designers to walk through it to make use of the opportunities towards solving the many issues confronting cities today, from sustainability to equity and from mobility to environmental justice.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA