An Elevator Company’s Challenge for Architects and Urbanists

Utopia. an imagined place or state of things in which everything is perfect. The word was first used in the bookUtopia (1516) by Sir Thomas More.

Even though urban life has globally become the predominant form of existence, the hunger for an urban Utopia, for an all different city in which all is perfect, has lost its luster. Too often has this been tried and failed, too often the results were mediocre or so far from “perfect” that the term has become a mockery. Architects such as Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright developed Utopian models, so did the landscape architect Ebenizer Howard and the entrepreneur Pullman. Architects like to quote Daniel Burnham that one should make “no small plans”. But the time when powerful or creative white men could cast a mold for others to adjust to has passed.

|

| Floating City: Utopia? |

This article will show how a global manufacturer of vertical transportation agrees and disagrees with that conclusion.

Not Utopia but pragmatic small steps, sustainability and resilience, in short, incremental progress is today’s preferred model, even though urbanization occurs at such a rapid clip, especially in emerging economies, that incrementalism seems inadequate where entire metropolises spring up within a decade. But instead of boosting Utopian aspiration, the sheer size, the speed of growth and the complexity of cities has become a deterrent for any attempt of achieving perfection.

Who should define “perfect”? Who should conceive and who implement an Utopian plan at a time when

cultures, values and ideas mingle freely. One’s Utopia is the other one’s nightmare. One of the purposes of cities is to allow and enable the collision of cultures and ideas; forcing them all into the mold of a particular perfection would be antithetical and stifle a city instead of making it flourish.

|

| Frank Loyd Wrights Ideal City: Broadacre |

But couldn’t plans be a bit more ambitious? A Swiss elevator company certainly thinks so.

Where strong authoritarian governments are in place as in the Arab Emirates or in China cities like Dubai, they follow a central plan and are imposed from above. Where governance is weak, as in parts of South America or Africa, self organization brings about the structures of emergence which some architects have discovered as Utopian (or dystopian) models for their own thinking.

| Hanging buildings in the Imax |

Environmental degradation, lack of water and climate change will dictate new urban paradigms to an even larger extent than any of the noted factors ever did. The environmental shifts, in turn, will have physical, social and economical implications. As a result even the search for a solid and functional “scaffold” may prove elusive. Even though, urbanists and planners cannot simply put their hands in their laps. Through interdisciplinary collaboration, research and a broad knowledge base they need to strive for concepts that stay ahead of the problems, anticipate the challenges and provide a framework in which a diversity of cultures and peoples can persist and provide a decent living in spite of adverse conditions. Why would a Swiss doctor turned electrical engineer participate in conferences about the future?

| The shelf: Sloping streets, parks |

And yet: One vendor decided to challenge the architects milling about on the exhibit floor: the Swiss elevator company Schindler. They carefully wrapped the provocation into an elaborate multi-part presentation in a rear corner of the hall, allowing them the placement of a over 7,000 sf tent city in which to hide a row of “rooms” formed by black cloth allowing a sequence of elaborate projection surfaces including an IMAX show. Schindler called it their immersive dome theater showroom In parts one through three of the hour-long high tech visual demonstration the vertical transportation experts predictably explained and sold their ware. In this case a new mid rise elevator that didn’t seem to be all that revolutionary in spite of bombastic words that promised to “change everything”.

But hidden into the mundane elevator product itself is the Schindler patented so-called PORT (Personal Occupant Requirement Terminal) technology which, indeed, is a revolution in the way elevators operate in large buildings. “Standard elevators are like airplanes where you board and then the pilot asks where you want to fly” said the engineer of Schindler’s Port system Dr. Paul Friedli to me in a chat after the presentation. Friedli, originally trained as a physician, is head of Advanced research at Schindler and participates in talks about innovation and transportation, including with the auto industry. (Video). In the new elevator dispatch approach, which is now widely in use across the globe, the dispatch of elevator cars are optimized based on a central demand input collecting several destinations. PORT technology reduces the core size because the efficiency of bundling desitnations results in fewer cars being able to bring folks to their floors. The method is well established and the fact that Schindler now offers a smart phone app that can replace the manual destination input isn’t an earth shaking or disruptive change.

What could be revolutionary, is the obvious potential of the algorithms of vertical transportation for horizontal transit and even for autonomous vehicles (Audi article). Applicable to campus shuttles, circulators and entire urban bus systems, making actual demand the base for dispatch would result in a smaller fleet of transit vehicles that could provide a much more efficient service than the fixed schedule service model that has been around for centuries.

|

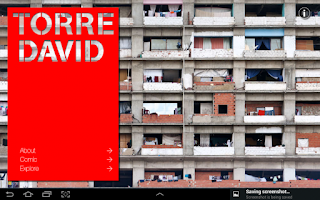

| Torre David: Self organized vertical slum |

Schindler had sponsored research on Caracas’ famous Torre David in which favela residents had taken over an abandoned, unfinished 45 story condo tower and occupied the first 28 floors ( the highest they felt they could go without an elevator). One of the findings of this model of self organization was that the absence of elevators fostered community in the building. People met each other. A startling insight coming from an elevator company!

This insight informed the concept of the first new urban living model in the film, “the urban shelf”. Essentially a midrise armature of slopes not unlike a Bjarke Ingels structure but instead of being completed it would remain unfinished for user controlled completion. The shelf is a raw flexible “scaffold” like a shipwreck becomes the home for a coral reef. The shelf gets completed over time and allows the same variety of uses from apartments to gardens and from offices to shops that had been found in the Caracas tower. The older Buckminster Fuller idea of hanging buildings (“inverted tower, inverted pyramid”) that save valuable ground space and allow storm water infiltration and other such drastic departures from standard building construction were beautifully rendered in the 3-D fly-trough as well.

|

| Paul Friedli: Schindler’s futurist |

Indeed, in this stomach-churning 3-D flight through the future the various options were depicted as collages in front of the backdrop of mountains that could be somewhere in Arizona. The Swiss, of course, are no need of any Utopia or innovative city. They have long realized their urban perfection in a decidedly old fashion: walkable, clean, plenty of mom and pop retail, streetcars, trains and bicycles, immaculate parks and conservatively dressed Swiss people eating cake in the afternoon on the sidewalk in front of a cafe. Diversity as frosting on the cake. Therefore, Schindler wasn’t entirely credible with their city of tomorrow, inspiring as it was.

Still, the Schindler show did ask the right questions. For example, what to do with a trend in which half the global population is expected to live in slums by 2050? (Friedli: “They have 24 hours a day to think about how they can live like you”, suggesting not too subtly major unrest and upheaval unless the dystopian slum future can be averted). How can the building footprint be reduced? How can large green spaces be inserted into cities? Can vertical and horizontal transportation merge? How can users be engaged and most importantly, how can people become happy and less isolated? A bit too tangential was the question of resilience against disaster.

The suggested solutions were radical enough to shake things up, while being small enough in scale to be immersable into existing urban systems. They addressed physical, social and environmental aspects including earthquakes, tsunamis and water shortage. Foremost, they would allow different people and cultures to flesh the ideas out in their own way. The ideas included in the Schindler film were truly scaffolds, armatures and frameworks from where all kinds of forms of living together could emerge. They were like green walls in which plants can grow, except in these concepts the plants were the people.

Only Neri Oxman of MIT expanded even further beyond our standard roam of thinking with her talk about bio architecture. Bio-mimicry, though could be seen as a natural extension of the structural models Mr Friedli had suggested. Her presentation almost got back to Utopia.

Even though the elevator vendor didn’t say so, in a way their future was one of a very different way of getting around. But what informed those rendered future wasn’t simply a futuristic mode like those helicopters that decorated obsolete Utopias of the past, it was the new paradigm of people responsiveness that permeated the entire presentation. Not a bad paradigm, one that may actually last beyond the next world expo.

Related article on this blog:

The History of the Future

Links:

Schindler Film

Ten failed Utopian City