Good Design Is Sustainable

Good landscape design is intrinsically sustainable. While a certain level of ecological sustainability may be achieved by adhering to a checklist of environmental best practices, long-term sustainability is achieved by engaging broader cultural, economic, and socio-economic goals. It's now widely recognized that city dwellers tend to live a less wasteful and more energy-efficient lifestyle than those who live in the suburbs or rural areas. So if well-designed urban public spaces are able to counteract the discomforts of high density, then more people will live happily, and sustainably, in cities. This was the crux of the argument made by landscape architects Martha Schwartz, FASLA, Ken Smith, FASLA, and Thomas Balsley, FASLA, in a recent panel discussion organized by the New York chapter of ASLA.

During the course of their long careers, these renowned designers have experienced two major shifts in the field of landscape architecture. One is the greater inclusion of ecological principles in design. The other is a shift in our cultural attitudes towards cities — from viewing them as unfavorable to celebrating them.

Each presented projects that engage sustainability on multiple levels and time scales.

Perk Park, a one-acre park in downtown Cleveland, was a vestige of 1970s-era landscape architecture when parks were designed as places to protect oneself from the stress of the surrounding city. "What happened, in fact, is that the space became inaccessible, it didn't have sight lines. There were places to hide. Eventually, people wouldn't even go in there, so it really held back the growth and vitality of the neighborhood," said Thomas Balsley. His firm, SWA/Balsley, re-designed the park so it celebrated and engaged with the surrounding environment, blurring the edges between the park and the city (see image above).

One popular element of Perk Park is its "urban porch," a linear pergola covering seating that lines the sidewalk. "You can sit at the porch and be in touch with the streetscape but also the park and be in dialogue with both." The park became so vibrant that local corporations and retail began to occupy the surrounding buildings, just to be near the park.

By preserving existing trees and including new permeable green space in the densest and most impervious area of a major city, basic elements of urban ecological sustainability were achieved. Moreover, by providing what Balsley calls "a stage for daily urban life to happen," the park achieves a long-term and nuanced form of sustainability.

"Really great design makes a difference, and it makes more of a difference than OK design," said Schwartz. "What we see affects us psychologically and emotionally. How a space looks can determine whether or not it will be used, and therefore maintained." The public will become active stewards of a well-designed space, but if a space is not considered valuable, "all the technologies and the well-meaning environmental practices we bring to it will disappear over time."

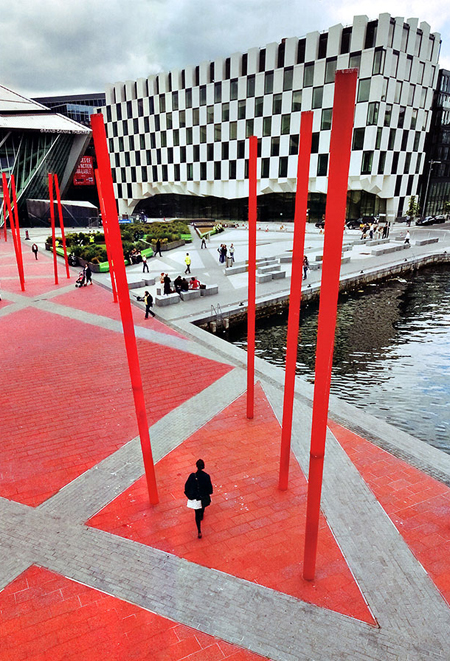

For Schwartz, a successful public space is both resilient and heavily used. She achieves these goals by weaving a narrative specific to each site, as well as creating landscapes that challenge and intrigue the public. Grand Canal Square by Martha Schwartz Partners in Dublin, Ireland, uses towering, off-kilter red poles, criss-crossing paths, and a paved red "carpet." Built before much of the surrounding development, the square's acclaim has ushered in economic resilience. The Dublin offices of Google and Twitter are now the square's neighbors, and the property values surrounding the square stayed steady during a time of economic downturn.

As part of the East River Waterfront Esplanade in Manhattan, which Ken Smith Workshop has been working on for a decade, Smith and his studio designed and built a prototype mussel habitat. Working with ecologists and marine engineers, Smith selected a concrete-textured substrate and designed a gradient of rocks to encourage the growth of mussel colonies.

In terms of providing a measurable ecological boost in the context of the East River, this 65-foot-long prototype of a constructed mussel habitat is likely only a drop in the bucket. However, being able to see the tides move up and down a slope as it fosters aquatic life is a unique sight in New York City, where hard vertical edges dominate the waterfront. Reminders that these natural processes occur amid the industry and infrastructure of the city can bring a sense of wonder to visitors, and perhaps encourage stewardship.

The common belief is that good design means sacrificing sustainability or vice versa. But these landscape architects challenged this assumption. Schwartz said: "To have something work sustainably in terms of its ecological processes, it doesn't have to look a certain way. Sustainability doesn't have an aesthetic. If you use your creativity, there's no reason why there is any separation between design and sustainability."