How Suburban Sprawl Is A Ponzi Scheme

Here's what Madoff did: He took people's money, promising a return on investment. In other words, he borrowed it. But the returns weren't real; the only way Madoff had to repay the investor was to borrow more money from a second investor, using the second investor's money to pay the first. But to pay the second investor, he then had to find a third. And so on, until he had run out of both money and investors. A friend's mother literally lost her life savings to his racket, which we now know as a "Ponzi scheme."

A Ponzi scheme, as described in Wikipedia, is a fraudulent investment operation that pays returns to separate investors, not from any actual profit earned by the organization, but from their own money or money paid by subsequent investors:

"The Ponzi scheme usually entices new investors by offering returns other investments cannot guarantee, in the form of short-term returns that are either abnormally high or unusually consistent. The perpetuation of the returns that a Ponzi scheme advertises and pays requires an ever-increasing flow of money from investors to keep the scheme going.

"The system is destined to collapse because the earnings, if any, are less than the payments to investors."

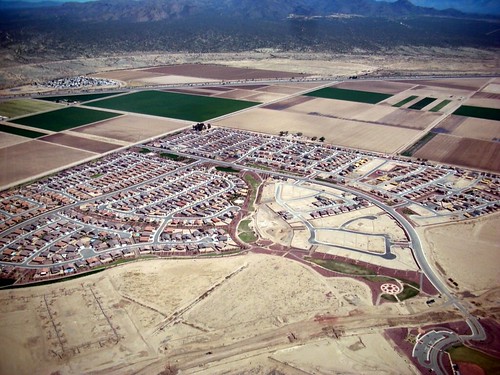

Sprawl development, says my analyst friend Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns, is basically a Ponzi scheme of its own. Municipalities chase tax revenues by extending infrastructure to accommodate new taxpayers.

Impact fees may help some, but not nearly enough, since at best they cover capital costs and not operating and maintenance costs. The real killer comes over time, when maintenance costs mount.

Ratepayers and taxpayers foot some of the bill, but few things are more unpopular than rate hikes and tax increases, so the municipality cuts services, borrows more money, or goes broke, sometimes all at once.

Chuck is not the first to point out the financial inefficiencies associated with sprawl. Robert Burchell of Rutgers has led several important studies showing the substantially increased municipal costs associated with sprawl development; my then-colleague Matt Raimi devoted a well-researched chapter to it in our 1999 book Once There Were Greenfields. At NRDC, we undertook a small empirical study in Cleveland and Chicago that confirmed the additional operating and maintenance costs associated with suburban wastewater infrastructure when compared with that in the cities.

But Chuck is the latest, and he is without doubt one of the best in explaining this rather dry subject (dinner conversation that won't happen often: "hey – c'mon over and we'll talk infrastructure costs!") to the likes of you and me. And he has now written a tour de force five-part series on the subject on his Strong Towns Blog. If you're not ready for the full adult dose, he has also helpfully summarized it in a single article on Grist.

In Chuck's words, here is the essence:

"What we have found is that the underlying financing mechanisms of the suburban era -- our post-World War II pattern of development -- operates like a classic Ponzi scheme, with ever-increasing rates of growth necessary to sustain long-term liabilities . . .

"In each of these mechanisms, the local unit of government benefits from the enhanced revenues associated with new growth. But it also typically assumes the long-term liability for maintaining the new infrastructure. This exchange -- a near-term cash advantage for a long-term financial obligation -- is one element of a Ponzi scheme.

"The other is the realization that the revenue collected does not come near to covering the costs of maintaining the infrastructure. In America, we have a ticking time bomb of unfunded liability for infrastructure maintenance . . .

"We've done this because, as with any Ponzi scheme, new growth provides the illusion of prosperity. In the near term, revenue grows, while the corresponding maintenance obligations -- which are not counted on the public balance sheet -- are a generation away."

Here's the series outline, with links:

The Growth Ponzi Scheme

- The Mechanisms of Growth - Trading near-term cash for long-term obligations.

Case studies that show how our places do not create, but destroy, our wealth.

- The Ponzi scheme revealed - How new development is used to pay for old development.

- How we've sustained the unsustainable by going "all in" on the suburban pattern of development.

- Responses that are rational and responses that are irrational.

Having followed Chuck's work for a couple of years now, I think he's been building up to this big synthesis of his research and experience for some time. He's done us all a great service by compiling it in one place (or five).

In his conclusion, he persuasively argues that we need to wring more value out of the places that we build, considering their lifecycle costs: "Will this public project generate enough tax revenue to sustain its maintenance over multiple life cycles?" Only by building upon already-existing infrastructure, and at a compact scale, can the answer be yes in most cases.

My favorite passage is the one Chuck leads with in his summary for Grist:

"We often forget that the American pattern of suburban development is an experiment, one that has never been tried anywhere before. We assume it is the natural order because it is what we see all around us. But our own history -- let alone a tour of other parts of the world -- reveals a different reality. Across cultures, over thousands of years, people have traditionally built places scaled to the individual. It is only the last two generations that we have scaled places to the automobile."

Highly recommended, especially if you are new to the financial aspects of development.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

Kaid Benfield writes (almost) daily about community, development, and the environment. For more posts, see his blog's home page.