LA's Little Tokyo Strengthens its Identity by Planning a 'Cultural Eco-District'

written with Thomas Yee

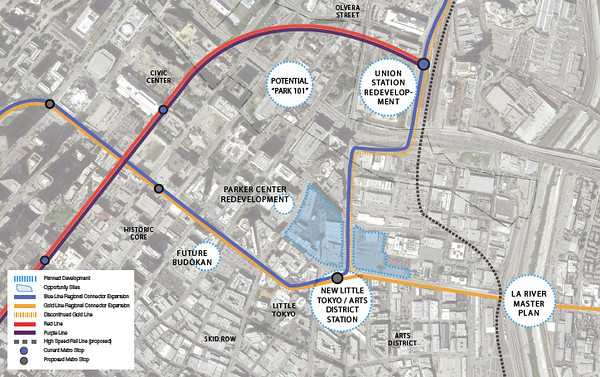

The Little Tokyo neighborhood in Los Angeles is one of the country's most important Asian-American communities. Comprising roughly five large city blocks, it has been maintained over the generations with ups and downs – including substantial depletion of population during the Japanese-American internment during World War Two. But today it is presented with immense opportunity, because it sits in the shadow of LA's city hall a short walk to the northwest, and at the junction of what will soon be two major transit lines (one line is already in place with a busy light rail station).

Change will occur in Little Tokyo: the question is whether that change can be managed so that it inures to the benefit of Asian-American residents, institutions and businesses, and whether it will be environmentally sustainable.

In short, Little Tokyo is a neighborhood in need of culturally and environmentally sensitive planning and development. The good news is that the community, led by the Little Tokyo Service Center, a community development corporation with over three decades of history in the neighborhood, and assisted by a range of partners (including the Natural Resources Defense Council), is taking control of its own future with a sophisticated and robust planning exercise. (Since 1979, the Service Center has worked in partnership with over 150 other organizations representing small businesses, Japanese international businesses, arts and cultural organizations, temples and churches, residents, and youth groups within the Little Tokyo Community Council.)

If the plan can be implemented as envisioned, the result could be the country's first "cultural eco-district."

The rich history of Little Tokyo

The Kito family first opened the Fugetsu-do Sweet Shop in 1903 to serve a small but growing Japanese population in the East First Street district of LA. Over 110 years later, third-generation business owner Brian Kito still operates the family business, which has survived the Great Depression, the forced internment of Japanese Americans during the war, the city's "Civil Unrest" of 1992, and the recent Great Recession. His family's story mirrors the larger story of the Little Tokyo neighborhood, which this year is celebrating its 130 year anniversary.

From just a few dozen immigrants in the late 1800s, as Little Tokyo first began to take shape, the enclave grew to tens of thousands within a three mile radius that stretched across to Boyle Heights and down to the Produce Market area. Over time, despite the disastrous effects of WWII internment and numerous periods of displacement and redevelopment, Little Tokyo settled into the outlines of the neighborhood today -- much smaller than in decades past, but in much the same location, centered around the First and San Pedro block, and recognized in the Federal Register of Historic Places. Around a thousand seniors call Little Tokyo home, and another few thousand new residents have moved into new luxury condos and apartments in Little Tokyo and the neighboring Arts District.

Neighborhoods like Little Tokyo make the city hum with culture and history, with opportunities for lower income families and seniors to still find decent housing at an affordable rent. The stories of these neighborhoods and their inhabitants need to be told and celebrated, and ought to be held up as real-world models of sustainability and resilience.

Formed in the days when racial covenants restricted communities like Japanese Americans to specific tightly constrained neighborhoods, Little Tokyo remains today because many generations have labored and persevered in the face of urban renewal, redevelopment, and suburban flight. Now the neighborhood is poised at a focal point for transit and smart growth policy, preparing (not entirely without suspicion and fear) to make way for a new era of increased density and young new urbanites.

Challenge and opportunity

In the past few years, the community resisted initial proposals for an above-ground version of the new light rail line, the "Regional Connector," that would have cut through its main commercial corridors. Instead, the neighborhood successfully advocated for an underground line that respected the economy and viability of the community. The new Little Tokyo/Arts District Regional Connector station is expected to become one of the busiest transit stations in Los Angeles County, and neighborhood representatives have been working hard with Metro (LA's transit authority) to ensure that the station enhances Little Tokyo's cultural and historic assets.

The neighborhood knows that more change is coming, and that it needs to be at the forefront of shaping that change, or risk being shaped by it. The next step will be formulating a bold, community-based vision for the inevitable real estate investment that will take place on the acres of public parking lots surrounding the new station.

In approaching its vision for an evolving neighborhood, the Little Tokyo community has been guided by three important questions that Manuel Pastor and USC researchers have articulated with powerful clarity:

- How do we achieve "just growth," and grow in a sustainable, equitable and inclusive manner as the region targets development around transit stations and transit corridors?

- Can historic and cultural neighborhoods remain true to their roots, or are we on a destructive path to water down these places into trendy interchangeable hotspots?

- How do we respect the role of real people as we pursue the important quest for reductions in vehicle miles traveled and greenhouse gas emissions?

The role of partnership

To achieve equity in transportation, growth, and development, we – all of us, including Little Tokyo –need to invest time and resources into lifting up and understanding our own stories, from the people in our own communities. We also need boundary-breaking partnerships that that can define and represent real sustainability.

Around two years ago, at about the same time that the Little Tokyo community was posing these questions and looking for ways to strengthen its future, the Natural Resources Defense Council was in the early stages of its green neighborhood initiative, a program designed to help struggling neighborhoods undertake sustainability planning and development. NRDC had already partnered with the Local Initiatives Support Corporation to assist community development in Philadelphia, Indianapolis, and Boston, and was seeking a new opportunity to further the work in another part of the country.

LISC, which has been and remains immensely supportive of sensitive, sustainable development in Little Tokyo, introduced NRDC's neighborhoods team to the Little Tokyo Service Center and, through the Service Center, to additional partners in the neighborhood. After several rounds of preliminary discussions, a partnership and planning process was born. The planning team soon formed productive working relationships also with Mithun, an urban design firm nationally known for sensitivity to local cultural issues, and Enterprise Community Partners, like LISC a national intermediary providing capital and other assistance to community development projects.

The planning vision

Through community conversations about residents' ambitions and aspirations for Little Tokyo, the partnership created a framework for sustainability that incorporates the community's desire to sustain a centuries-old local economic base of small businesses, enhance a mature social community fabric, and embrace cutting edge green technologies to conserve resources and cut the neighborhood's carbon footprint. Importantly, the process is rooted in long-held cultural and community values passed down from generation to generation, such as "Mottainai"(what a shame to waste), "Kodomono tameni" (for future generations), and "Banbutsu" (interconnectedness), and inserted into a contemporary environmental context.

After months of preliminary meetings, the partnership staged a community planning and design charrette for over 200 participants with the help of an expert team of architects, planners, engineers, and market economists. In particular, the team asked participants to imagine themselves walking out of the light rail station into Little Tokyo, 20 years into the future. The partners listened to formal and informal conversations, and together with community members sketched those ideas into a tangible range of scenarios.

Armed with decades of shelved master plans for sculpture gardens, massive skyscraper developments, and pedestrian linkage studies, the community and its partners crafted an exciting, balanced and comprehensive development vision that can simultaneously achieve deep affordability targets, provide commercial and cultural facilities that enhance the neighborhood's existing assets, and open up new park and plaza spaces for formal and informal gatherings.

The vision starts with a plan for equitable transit-oriented development around the new light rail station at First Street and Central Avenue. It also proposes an ambitious set of cutting-edge environmental features, including district-scaled green infrastructure -- district heating and cooling, stormwater collection planters, "living machine" graywater filtration landscaping, and a mini-solar electric grid.

It's more than just a development scheme: the partners are creating a model we are calling a Cultural Ecodistrict, a framework for achieving environmental sustainability in the context of historic and cultural neighborhood preservation. We hope to emulate what performance artist Nobuko Miyamoto and Great Leap have already begun to achieve in the arts, marrying environmental values with cultural traditions and creative vision.

The next step will be to bring the city, which has been an active observer of the planning process, on board with appropriate development guidance, zoning, and regulatory detail. Metro's blessing will also be important.

It took almost five years to get the planning of the regional connector line and station right. It took two years of discussion and planning to generate the community vision. And it likely will take another five to ten years to realize the vision. In other words, participatory planning is hard work, and to do it right it takes patience and dedication. But we believe it will be well worth the effort.

Thomas Yee is the Director of Planning at the Little Tokyo Service Center, a Community Development Corporation.