Reconnecting People with Nature through Architecture and Design

Image courtesy of Whitney Hopkins.

Poorly conceived design divides us in urban areas from our wilds and has contributed to seeing nature as something isolated from us; this actually diminishes us. This post details how architecture and urban design can bring us back to nature, in schools, cities, workplaces and hospitals, with numerous benefits.

By Whitney Hopkins, Vail & New York City

“The more we know of other forms of life, the more we enjoy and respect ourselves…Humanity is exalted not because we are so far above other living creatures, but because knowing them well elevates the very concept of life.” — E.O. Wilson

A recent, satirical New Yorker piece by Andy Borowitz quoted a fictitious resident who blamed scientists “for failing to warn us of the true cost of climate change. They always said that polar bears would starve to death, but they never told us our lawns would look like crap.”

Although this does not represent a real person’s exact feelings, the underlying sentiment sadly has more than a hint of truth. To many people, the impact of a changing environment seems distant and completely separate from our existence until we are directly confronted with the negative results.

Poorly conceived design divides us in urban areas from our wilds and has contributed to seeing nature as something isolated from us. Yet reinvigorating our bond with nature is a challenge architecture and urban design are well placed to address.

Architects and designers have control over our built environment; by changing the way we design cities and buildings to connect to rather than disconnect from nature, we can change our proximity to nature and shift our physical relationship to the environment.

Photo: Schristia. Creative Commons.

The separation that we have crafted over the centuries through our isolating designs hasn’t come without costs.

Obesity, ADHD, autism, a decline in creativity—these are all connected to a lack of environmental connection.

Unfortunately, this estrangement from nature has not only directly impacted our health, it has impacted our ability to respond to crucial modern challenges, such as climate change, because these dire environmental topics feel removed from us.

The environment appears distant because we designed it as such. Sim Van der Ryn and Stuart Cowan describe this impact in their seminal book, Ecological Design:

“What do we learn from this kind of ‘nowhere’ environment? When living and working in nowhere places becomes normal, it is no wonder that we literally lose some of our sensitivity toward nature.

Through the daily experience of the designed environment, we learn detachment… As nature has receded from our daily lives, it has receded from our ethics.”

Yet despite putting up physical barriers between nature and us, we still cannot shake our deep tie to and need for other species.

Humans have an ingrained desire to connect. E.O. Wilson describes this impulse in his ‘Biophilia Hypothesis’ in which he explains,

″…When human beings remove themselves from the natural environment, the biophilic learning rules are not replaced by modern versions equally well adapted to artifacts. Instead, they persist from generation to generation. For the indefinite future… urban dwellers will go on dreaming of snakes for reasons they cannot explain.”

We crave connection to the natural world, even if we, individually, have always been seemingly divided from it.

By calling architects and urban designers to ‘Make Nature Visible,’ as Van der Ryn and Cowan request in Ecological Design, we can begin to design places grounded in their own unique environment.

In this way, designers can revive an awareness of the natural systems that affect us and recover place-based knowledge.

The advantages of interacting with and seeing nature are numerous. Beyond technical benefits, feeling the presence of the living world around us elevates the spirit.

Supporting this movement, many architects and urban designers are inventively finding ways to reconnect us with the touch and feel of our wider biological community.

Photo credit: Thorbjõrn Hansen

Schools

Children seem particularly moved by biophilia and quickly gain many advantages from access to the outdoors.

Schools that get children outside into natural places find that their students perform better academically (this has proven especially true for low-income students) and are more engaged and motivated to learn.

These benefits come in addition to decreasing the need for disciplinary action, reducing stress, and increasing student attention spans.

But the gains are not just performance-based—it turns out that the outdoors even improves vision and increases Vitamin D levels, all advantages that make students healthier.

There are some great schools that strive to put children outside and reflect this philosophy in their design.

Photo credit: Thorbjõrn Hansen Daycare Center in Holbæk, Denmark

Sitting at the highest point in the neighborhood, the daycare center on the outskirts of Holbæk, Denmark provides a base for an outdoor-oriented school.

Teaching children outside has long been a traditional education approach in Denmark, with ‘forest schools’ dating back to the 1950s.

This daycare, designed by Henning Larsen, includes large south-facing windows, a green roof, and gardens to allow children to play outside throughout the entire year.

Fuji Kindergarten in Japan

Physically encircling a tree, the innovative Fuji Kindergarten, designed by Yui and Takaharu Tezuka, highlights nature as a teacher every day.

The children can play on an outdoor structure that surrounds the tree, climb the tree itself, or just admire the tree from every room in the school.

The school furthers its connection to nature with lots of glass and open air, which means the outdoors flow seamlessly into the indoors.

Photo by Katsuhisa Kida/FOTOTECA.

Bronx Zoo School Proposal in the Bronx, New York

In the New York City borough of the Bronx, few people have close interaction with their natural environment. This proposal, which I designed for a public school in the Bronx zoo, was aimed at rectifying this problem.

Our connection to the ecological systems becomes apparent day-to-day through this school’s open architecture and outdoor classrooms and is bolstered by the whooping crane breeding program, which is integrated into the school and managed by the students.

Hospitals

Connecting patients to nature has been innately valued for centuries—the first health centers were at remote monasteries intended to foster the tie between healing and the environment.

Now, a growing body of modern scientific evidence supports this notion; patient outcomes appear to be closely related to interacting with nature.

Connection to the natural environment has been shown to improve overall healthcare quality in multiple ways by reducing staff stress and fatigue, increasing the effectiveness in delivering care, improving patient safety, and reducing patient stress.

All this leads to improve health outcomes and patients who are happier and heal faster. Hospitals foster this by having views, natural light, and access to gardens or the outdoors.

The few following hospitals do this exceedingly well.

Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula in Monterey, California

Designed in the early 1960s on the California coast, the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula was ahead of its time in pulling the outdoors inside a healing environment.

The patient rooms and public spaces have large panoramic views of the surrounding forest, gardens, and courtyards and a flow between all the indoor and outdoor spaces.

It has been recently expanded and remodeled by HOK to be state of the art while maintaining the original natural tranquility.

Photo: Frank Keillor. Creative Commons.

Children’s Psychiatry Center (KPC) in Genk, Netherlands

In an artistically crafted, patient-centric building, the Children’s Psychiatry Center in the Dutch city of Genk innovatively marries a designed outdoor environment with the hospital.

Children’s well being was at the core of OSAR’s design, so every space in the center captures views of internal courtyards, gardens, or the forest.

In so doing, the hospital reduces the stress of the patients, their families, and the staff and creates a safe and warm atmosphere within the center.

Children Psychiatric Center, Genk, Belgium. Photo courtesy of OSAR. www.osar.be

Workplace

Because the evidence of diverse benefits is so strong, contact with nature in the workplace has become a central element in the design of healthy office spaces. Various studies have repeatedly shown that access to outdoor gardens or parks, indoor plants, and windows with views of natural places reduce worker stress levels.

Beyond manipulating stress levels, it appears that employees are also happier and more productive with a connection to nature.

And firms greatly benefit because sick leave and worker turnover is reduced.

With all these advantages, it is no wonder that creating contact between nature and workers is happening in offices, manufacturing plants, and every type of work environment in between.

Photo by Greg Williams. Creative Commons.

Ford Rouge Factory in Dearborn, Michigan

A historic manufacturing facility that had been deemed a heavily polluted brownfield site, Ford transformed the facility into a vibrant, sustainable new factory.

Nature takes center stage at the facilities, which boast the largest green roof in North America, various treatment ponds and gardens, natural vegetation, and ample day lighting.

As a result, the productivity of the workers increased and sick days decreased.

One complaint: the amplified bird poop from the population that has taken up residence on the factory premise.

Selgas Cano Offices in Madrid, Spain

Within the urban area of Madrid, the architectural firm of Selgas Cano made waves with their design for their own office.

Sunken into the ground, curved glass opens the office up to spectacular and unusual views of the surrounding woods.

The space is filled with natural light that bounce of the bright interior colors.

Reportedly, employees love working in the space.

Selgas Cano Office. Photo: Iwan Baan.

Cities

In urban areas, the expanse of human construction can particularly estrange people from the environment, so it becomes crucial to consciously give residents access to natural places.

A recent Danish study by Stigsdotter and colleagues found that people who lived more than 1 kilometer away from green space were generally less healthy.

They also showed worse vitality, were at higher risk for depression, and reported higher levels of stress and pain.

These advantages must partly contribute to the increased values of real estate adjacent to urban green space.

Some cities are working hard to bring nature into the urban core by creating or revitalizing parks and seeing green space as an essential element in their infrastructure.

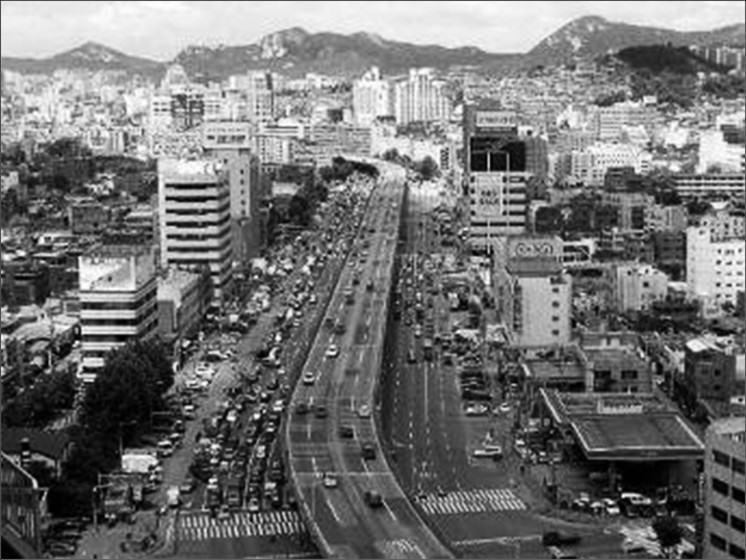

Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul, with a highway running over it.

Cheonggyecheon in Seoul, South Korea

A stream runs through the center of Seoul, but for decades, most people would never have known.

After years of polluting the Cheonggyecheon river, the city covered it in 1968 with an elevated, 8-lane hightway, hiding the river from view.

But in 2003, the mayor began an initiative to improve traffic and restore the river.

The Cheonggyecheon park opened in 2005, bringing people into close contact with the water and newly established parks through a central urban corridor.

This project revitalized the local busineesess, improved transportation, and made the citizens happy by providing them with a delightful green space and reconnecting them to their historic river.

Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul. Photo: David Maddox

In partnership with nature

With nature providing such joy and many health benefits, it is time that architects and planners leverage designs that highlight the environment in our built spaces.

We can hope that beyond making a healthier and happier world, we can also prompt a more ethical relationship to nature.

As Sim Van der Ryn and Stuart Cowan conclude:

“Design transforms awareness. Designs that grow out of and celebrate place ground us in place. Designs that work in partnership with nature articulate an implicit hope that we might do the same.”

Whitney Hopkins is a designer in architecture and product design. She is interested in how design shapes society and the environment and has expertise in empathy, sustainability, and biomimicry.