Overcoming US Highway Injustices: From Displacement to Opportunity

|

| Anthony Foxx speaking about urban freeways at the Center for American Progress last week |

"The people in my community at the time these decisions were made were actually not invisible," he said. "It is just that at a certain stage in our history, they didn't matter....Businesses didn't invest there. Grocery stores and pharmacies didn't take the risk. I could not even get a pizza delivered to my house". [...] "roughly two-thirds of the families displaced [across the US] were poor and mostly African American".

| Encircled by freeways: African American Community of Butler, Ft Worth, Tx (photo: ArchPlan) |

Principle one: While transportation needs to connect people to opportunities, it should also "invigorate opportunities within communities."

Two: Projects need to take into account communities that "have been on the wrong side of transportation decisions," and figure out ways to make them stronger.

And three: The projects should be built for and by the communities they go through.

"Robert Moses wanted to plow through a West Baltimore community known as Harlem Park, a then-thriving middle-class African American neighborhood. Harlem Park was destroyed before the project was stopped." (Foxx)

|

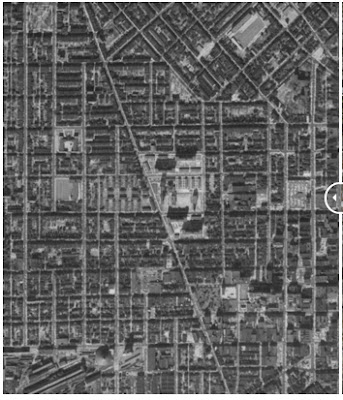

| West Baltimore before the freeway (the diagonal is Fremont Ave) |

|

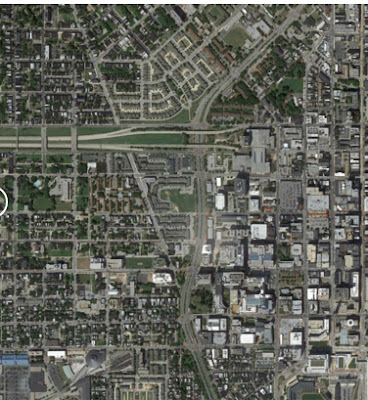

| Baltimore after the freeway and Martin Luther King bypass (the diagonal is Fremont Ave) |

I think people tend not to notice or to pay attention to issues of transportation and transportation infrastructure as a civil rights issue and it's one of the matters I've been pressing. Because access to jobs, access to mobility, reducing housing segregation, all of these things are deeply dependent on transportation decisions that happen in many ways out of sight and out of mind.

So these highways were built for the convenience of whites and to support and invigorate the white middle class. And very often this was done at the expense of African-American communities. [...] I would have to say that this continues to this day (Sherrilyn Ifill on NPR's Diane Rehm show).

There is a regrettable legacy of aligning and designing transportation projects that separated Americans along economic and even racial lines. At a time when our nation has so much infrastructure to repair and replace, we have a chance to do so in a much more inclusive way that will simultaneously expand economic opportunity and socioeconomic mobility throughout America. The choices we make about future transportation projects, to the people they touch and places they connect, will play a role in determining how widely opportunity expands throughout America. (Ladders of Opportunity website).

| Interstates immediately accessible from downtown St Louis (photo ArchPlan) |

But the best intentions on the federal level won't go anywhere when local or State policies derail them. In his speech Secretary Foxx explicitly mentioned Baltimore and the sad example of the Red Line, a fully designed $2.9 billion New Starts project that the newly elected Republican Governor chided as a "boondoggle" and canned in spite of a considerable federal commitment.

"We had planned to commit about $1 billion to this project, only to have it cancelled by the state of Maryland," Foxx.

The Baltimore NAACP and other groups have filed a civil rights complaint in response to Governor Larry Hogan's Red Line decision.

Back in Robert Moses times Baltimore and Washington became frontier cities in a national movement against urban freeways. Baltimore activists had recognized even then that the fight required collaboration between the black communities on the west and the white ones on the east. A city-wide interracial coalition against inner-city expressways called Movement Against Destruction (MAD) was created and prevented the demolition of 28,000 housing units, saving numerous stable and historic neighborhoods and saved the city's Inner Harbor from a massive downtown expressway interchange. Senator Barbara Mikulski began her political career in this fight. The other side, the freeway proponents were not all simplistic bigots or city haters. Many groups tried to improve the various alignment proposals and employed community centered arguments to promote the projects. They argued that the investment in freeways could leverage community investments and for the east-west highway they included transit in from of a metro line in the median of the freeway with stations envisioned as development hubs, not unlike the current talk about TOD.

But as noted, the saved communities were mostly white and the two only realized elements of the freeway plan, the Highway to Nowhere and a short downtown leg off I-95, both displaced African Americans in established vibrant communities such as Rosemont, Harlem Park and Sharp Leadenhall. The community investments never materialized, nor did the metro line; instead the now bifurcated neighborhoods never recovered from the blow and decay accelerated. in the affected communities this legacy was never forgotten. Mistrust has tainted almost any discussion about transportation in Baltimore ever since.

|

| The Baltimore "highway to nowhere" in winter: a bleak canyon |

When Maryland's newly elected Governor canned the the shovel ready east-west surface-subway rail line which had been slated to become the transit successor of the aborted east-west highway, the opportunity of giving that bit of freeway some purpose evaporated and with it the promise of the much needed access for the isolated and dis-invested communities that Robert Moses had described as slums.

The old smokestack centers of early industrialization need that shift to a new knowledge economy more urgently than the newer sunbelt cities. Access, collaboration, communication, partnership, openess and information are the necessary attributes which must replace exclusion, separation, and division.

NPR's Diane Rehm Show with Secretary Anthony Foxx

Richard Rothstein: From Ferguson to Baltimore

A Departure From Decades of Highway Policy (Atlantic Magazine)

The Role of Highways in American Poverty (Atlantic Magazine)

The Interstates and the Highways (Mohl)

The Baltimore City Interstate Highway System (UM, Prof Garrett Power)

Before and after pictures, 60 Years of Urban Change

More Cities are razing Urban Freeways (Christian Science Monitor)

Freeways and the decline of St Louis

The Road that Goes Mercifully Nowhere (This Big City, 2013)

This article is accompanied by a series of articles on my local daily blog that highlights a number of the Baltimore traffic follies.

|

| Providence, RI before freeways |

I think people tend not to notice or to pay attention to issues of transportation and transportation infrastructure as a civil rights issue [...]. Because access to jobs, access to mobility, reducing housing segregation, all of these things are deeply dependent on transportation decisions that

|

| Providence, RI, after freeways |

happen in many ways out of sight and out of mind. (Sherrilyn Ifill, NAACP).

I think we've recognized the failures of a mobility-first framework and the metrics that we've used just to measure how fast we can move vehicles and the need to connect people to economic opportunity. And so places like Denver, places like Chicago, places like Kansas City, San Francisco, are all at the forefront of doing this. (Robert Puentes, Brookings Institution)