Reshaping Growth Centers with Open Space = Smart Growth

Ostensibly, smart growth emerged as a way to save nature and preserve open space. Draw a growth boundary, went the thinking, on one side is human development and on the other is nature. Natural lands seemed too threatened by the insatiable growth of roads, subdivisions and roadside businesses to let it go on forever.

Of course, it has gone on anyway. In Maryland, the total land area developed in the 30 years between 1970 and 2000 exceeds all lands ever developed before 1970. And now as we write in 2015, one might think that the smart growth laws have hardly made a dent.

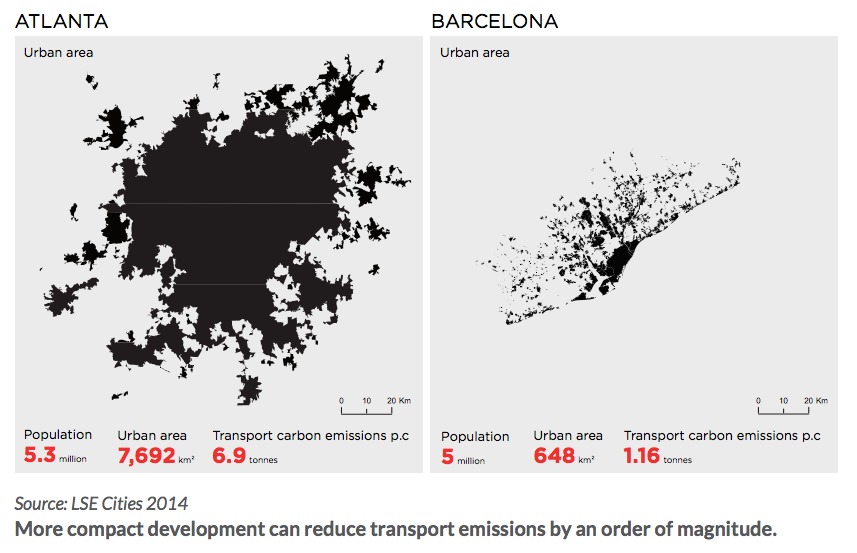

Footprint of Atlanta versus Barcelona (same number of residents)

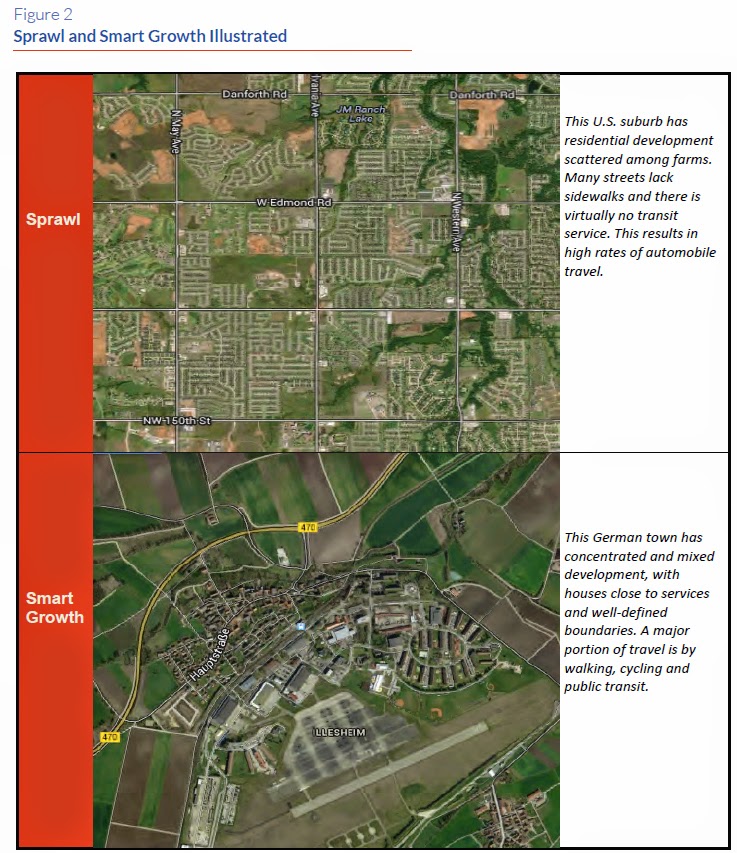

Aerial comparison between typical US development pattern and a typical German small town.

As someone who has written again and again about sprawl and how it bankrupts American communities and economies, I was very pleased to see this report mentioned in CityLab with the following somewhat bulky title: Analysis of Public Policies That Unintentionally Encourage and Subsidize Urban Sprawl.

The original discussion of protection of natural lands, resulting in the Oregon growth boundary and the Baltimore County URDL line, both implemented as early as the Seventies, was followed by a broader discussion of sustainability and efficiency considerations. Traffic seemed to become worse and worse the further out people fled from it. Just as available lands were finite, so too were resources to build infrastructure or maintain an ever larger amount of it. "Sprawl costs us all," environmentalists proclaimed as they had learned to couch their arguments in economic terms. The already noted new summarizes all the bad fiscal and environmental consequences neatly, convincingly and in great detail.

But notwithstanding all studies about the ineffectiveness of the sprawl model and the recognition that infrastructure can't keep up, the exponential expansion of roads, water, sewer, electric lines and everything else continues to ruin the budgets of local government. One need to only look out an airplane window on a clear night and west of the Mississippi finds lights glowing everywhere. Increases in urban living, in transit use, share models and less driving have only nibbled at the devastating energy footprint that our lifestyle begets. But these new trends have the potential to render much of what we see on the ground obsolete in short order.

In Smart Growth 3.0 the discussion finally shifted focus from quantitative limitations to one about quality. No longer is the smart growth debate simply about protecting nature from human development or one about what is the most efficient system. The new discussion about quality is harder to avoid. Too many people have taken a hard long look at what sprawl has created and decided it is not for them. The quality debate may not simply come from being tired of sprawl but from demographic shifts that make the sprawl model less attractive for the two largest cohorts currently populating the US: The aging "boomers" and their children, the Millennials, who are sick and tired of the "more is more" approach of their parents.

All this has been well documented; it is time to look more carefully at what happens inside the development envelopes, in the "priority funding areas" (a Maryland smart growth term), and designated town center areas. Maybe surprisingly, this discussion once again begins with open space.

The open space and development duality that had been seen in antagonistic or mutually exclusive terms of the "inside and outside game" in the sense that development is "inside" and open space "outside" neglects to recognize how important open space is also inside the growth boundaries. Open space there must not be seen as a competing use but an enhancing one.

To illustrate this, it has become almost trite to point to Central Park in Manhattan as an example. Yet, as obvious as this example is, it is still poorly understood how dense development requires the protection of open space not somewhere beyond a growth demarcation line or "out west" (where huge unsettled amounts of land still make the United States overall a sparsely populated country) but right where the density occurs. This is as true in designated town centers and growth areas as it is in Manhattan.

How poorly this is understood can be studied in Baltimore County, a mostly suburban area with a historic center (Towson) and two designated growth areas. County administrations gave developers a free pass on the requirement to provide open space in just those areas where development pressure is the highest, open space, most in short supply and where dense new development also creates the highest demand for open space. This happened even though providing open space or paying a fee in lieu is well established in the County's code and is usually enforced in the low density areas.

The developers of all major residential and mixed-use subdivisions are required to provide a minimum of 1,000 square feet of Local Open Space (LOS) per dwelling unit on the development site. Requirements for LOS are contained in Sec. 32-6-108 of the Baltimore County Code , and the Local Open Space Manual, which is prepared and updated by the departments of Planning and Recreation and Parks, as mandated by the County Code.

The Department of Recreation and Parks may grant a waiver of part or all of the requirement to provide LOS on the development site, subject to a finding. When a waiver is granted, the developer is obligated to pay a fee in lieu of open space. The LOS fee is to be credited to a separate and distinct revenue account within the Recreation and Parks Department's capital budget.

If the dialectic relationship of open space and development would be better understood, it wouldn't have been necessary for hundreds to crowd into the county planning commission's public hearing on "open space waiver fees" to demand that town center developers either provide or pay for open space. Well-known local landscape architect and planner Scott Rykiel gave a voice to the absurdity of the situation when he exclaimed "that communities all over the country demand open space fees from developers" and that as "someone who plans open space for a living" he found it "unbelievable we have to [testify]."

The truth is that most zoning in the US, be it urban or suburban, has not caught up with the new concepts of place making, urbanism, mixed-use and form and space based planning. In many instances, open space is not even a zoning category. It is no surprise, then, that requirements for open space often have not caught up to the insight that smart growth, dense, mixed-use urban development and open space preservation go together and are not opposites. Too many regulations are still mired in the post war pattern of use-segregated subdivisions, the fragmentation of everything, including the privatization of green space as it manifests itself in private lawns and in formulas which require developer set asides of open space. Those set-asides did little more than designate leftover spaces and buffers resulting in a patchwork of green that is essentially useless for public use, placemaking or a green infrastructure network.

How complicated, hard to understand, not transparent and full of unintended consequences Baltimore County's open space and waiver fees requirements really are becomes clear in an analysis that the county council had commissioned from the planning department. A report version that was subsequently scrapped because the matter seemed too hot for the administration included this observation:

The amount of LOS that the county requires developers to reserve on site is the same for each dwelling unit to be built, regardless of zoning class. But the waiver fees vary and are widely divergent in some cases. By requiring the same amount of LOS for each dwelling unit, if provided by the developer on site, while assessing divergent fees if the provision of LOS on site is waived, the county effectively encourages waivers in some zones while discouraging them in others, and imposes disproportionate burdens on developers based solely on the zoning of their development tracts.

The report continues a little later on to describe how illogical the complicated rules are:

While the fee is lowest for the zone with the lowest density limit, and highest for the zone with the highest density limit among the DR and RC zones, this general rule is turned on its head when all of the zones are considered together. The RAE zones and the CT district permit higher densities than any of the DR or RC zones, yet they are effectively exempt from all or part of the LOS fee. The fee of zero dollars for either the first 124 units, or for all of the units in a development, makes these fees the lowest for any of the zones.

A study of the thicket of open space regulations in various jurisdictions brings about more questions than answers:

- Should requirements favor construction of actual open space or the payment of fees which allow the jurisdiction a more coordinated approach of providing green spaces?

- Should the requirement for space be limited to residential use and if so, should it be based on the number of dwelling units to be developed, on the gross area of development or even on the cost per square foot?

- Should the fee in lieu be based on the cost that a developer would incur should he provide the space himself or be based on the cost that the jurisdiction would have when trying to build an offsite mitigation space?

- Should the cost of green space be based on assessed raw land values or on the cost of improved actual green space built per the design standards?

- Should the fee structure create incentives for developing in designated growth areas and disincentives for building outside of them or should it be strictly be based on the needs for open space created by a development

- Or should fees be scaled according to the already existing needs, i.e. highest where existing supply is the lowest?

Unfortunately, these questions remained largely unanswered by either the draft or the final staff report of Baltimore County's planning department. An initially suggested flat fee was not only way to low, it also ignored that neither needs nor cost are uniform across the county, thus, a flat fee would have once again benefited the big developers who engage in high impact developments in town center and growth areas while penalizing smaller home builders who do a batch of a few dozen individual homes here and there.

The design guidelines and the fees for open space need a complete re-think, one that doesn't consider open space a leftover but an organizing element. In my 2012 blog article, Open Space - The Stepchild of Planning I wrote this:

In the US, the maybe most famous American landscape designers, Frederick Law Olmsted and his sons, the Olmsted brothers, began in the 19th century to see open space not just as the absence of development but as an organizing piece: Man-made nature surrounded by development. They designed parks as centers, as magnets that hold everything together, as real three dimensional spaces that were indivisible from development itself. The Olmsteds foresaw the future and helped shape it. The park as organizer, as catalyst, as vital resource, a far cry from being just the passive absence of development.

Orange County, CA

Older east coast US cities all have those defining and often famous parks and open spaces. Most suburbs don't. In retrofitting suburban centers open space is the ace card. Requirements and fees are not there to repel or sink development but to make it more valuable in the long run. Only shortsighted developers would fight that.

By Klaus Philipsen, FAIA, edited: Ben Groff