Smarter Land Use: Helping Cities Attract Young Adults

The prolific urban observer Richard Florida has been telling us this in various ways for years, as he researches and charts the shifting economic geography of the US. He believes the housing and finance industry collapse of the last few years signals the end of one economic era and the beginning of another, though I'm sure he would be the first to tell us that we're in a messy and hard-to-pin-down transition. But he is clear that the new economy – based less on manufacturing and established institutions, more on creativity, entrepreneurship, connectedness and interaction – will prosper best in places suited to a new kind of lifestyle, one that has already emerged in leading cities.

In his book The Great Reset, Rich puts it this way:

"Every major economic era gives rise to a new, distinctive geography of its own. This Great Reset will likewise take shape around a new economic landscape and a whole new way of life that is in line with the emerging economic and social realities of our time . . .

"One thing is certain: this emerging new way of life, which some already refer to as an impending 'new normal,' will be less oriented around cars, houses, and suburbs."

I've been mulling this for a couple of weeks, since I ran across an excellent report written in 2009 by Jonathan Rose Companies and Wallace Roberts Todd for the Hartford metropolitan planning organization (the report was supported, like the Greening America's Capitals study, by the federal EPA). Reading it, I was surprised to learn that there has been a major decrease in Connecticut's population of 25-to-34-year-olds, which dropped by 30 percent from 1990 to 2006.

Combining all age groups, the state as a whole grew during that period, albeit half as fast as the national average. But it did grow faster than some and much faster than, for instance, neighborhing Rhode Island. As we all know, there's major industry in Connecticut, and I'm told that it also has very high average housing prices compared to the rest of the country, suggesting that there is continuing demand.

So what's the problem? Why is Connecticut losing so many of its young adults? And what do the facts suggest for other places hoping to prosper in the new economy?

I'm not going to say that the reasons for this apparent "brain drain" are all about the built environment – there must be multiple economic factors in play – but the Rose-WRT report says just that:

"The primary reason for this drop is an outmigration of this younger demographic group due to a lack of housing choices that are affordable, convenient and desirable. Housing that is affordable and also conveniently connected to jobs, transportation, and quality neighborhood services became increasingly scarce, while median home prices in the State continued to rise. Meanwhile, recent trends have shown that younger homebuyers and empty-nesters are rejecting large-lot suburban homes for smaller homes in compact, walkable communities. This marked decrease in its young workforce sector represents a real risk to a loss in the region and state's economic competitiveness."

My take on it is that, whether or not there is direct causation between Connecticut's losses and the housing choices in its cities, those communities – in Connecticut and elsewhere – that have the kinds of urban (and walkable suburban) environments preferred by Millennials are the ones that will be best positioned to attract and keep young people that have choices about where to live.

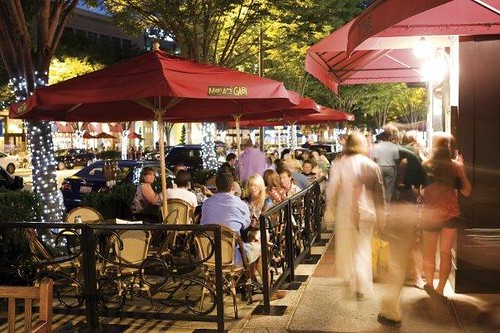

As a result, Dublin is now in the midst of creating a major walkable, lively, mixed-use district with a terrific master plan and appropriate rezoning that the city is fully behind. As I understand it, significant parts of Phase One are now in development on the gigantic surface parking lots that the corporations had built.

I (and others) have written often about changing housing preferences, including in this recent article triggered by some analysis from Ben Brown of PlaceMakers. My friend and real estate analyst Laurie Volk has been presenting the data for the last few years at forums in which David Dixon, who led the Dublin planning exercise, and I have co-presented. She believes there is a "great convergence" as the two largest generations in American history – the Millennials and the Baby Boomers – are now playing major roles in the housing market. The Millennials are entering the market with a preference for urban lifestyles at the same time as a significant number of downsizing Boomers no longer want large houses and yards to take care of.

I remembered that the real estate consultancy Robert Charles Lesser & Company had done some great research on Millennials in particular, so I went to their website to read the reports. Here's what their research (defining the generation as those born from 1979 to 1996) says about the group's housing preferences:

- 31 percent prefer to live in a core city (this number is double that of previous generations at the same age).

Two-thirds seek walkable places and town centers, even if their preference is to live in a suburb.

- On third is willing to pay a premium to be able to walk to shops and amenities.

- Half are willing to give up living space in order to live in a walkable neighborhood.

- They value diverse neighborhoods, proximity to jobs, and fun, with more emphasis on connectedness and life/work balance than their predecessors.

The hottest current market in real estate, by the way, is multifamily rental properties. In some locations, that is the only portion of the market that is doing well.

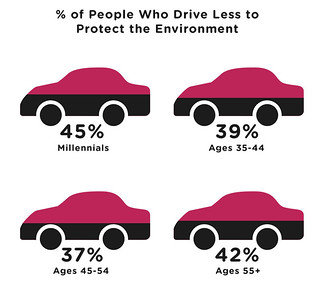

Millennials also have very different transportation habits than previous generations had at the same age:

- 26 percent do not have a driver's license (up from 21 percent only a decade ago).

- Miles driven by ages 16-34 have dropped an impressive 40 percent per capita in a single decade.

- Bicycle trips in the age group rose 24 percent in ten years.

- Walking is up 16 percent from a decade ago.

- 45 percent report making a conscious effort to replace driving with alternative forms of transportation.

So those are the changes in market characteristics. I didn't undertake sophisticated analysis of how well Connecticut's characteristics matched up with those preferences (I know that nationally we have an oversupply of large-lot housing when compared to future demand, and an undersupply of other types). But I did look at basic census data to get a general sense of what has been happening in growth trends in Connecticut. The state as a whole grew 4.9 percent in the last decade. That rate was low enough that I expected to find some communities gaining and others losing. I was right.

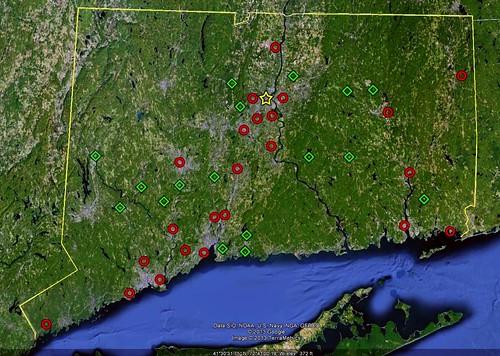

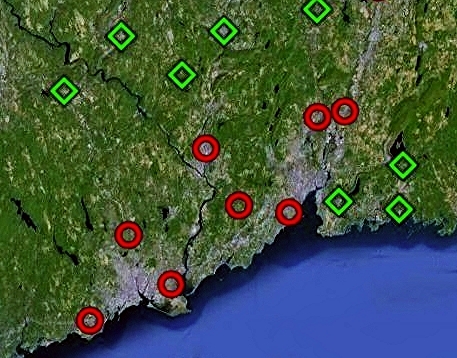

I then made these maps to depict the geography of significant population gains and losses in the state from 2000 to 2010.

The bottom two images are close(er)-ups of, on the left, metropolitan Bridgeport and New Haven; on the right, metropolitan Hartford. The red spots indicate municipalities of 10,000 or more residents that had either no population growth or a population loss from 2000 to 2010. The green spots mark municipalities of 10,000 or more that not only grew, but did so at a rate faster than the state's average.

Sure enough, the places in decline are, for the most part, established urban and older suburban: areas that have existing investment and infrastructure that would be well-suited for reinvestment and revitalization. The places that are showing fast growth are in more rural areas that likely are not the walkable and highly connected environments preferred by today's young adults. (They are also where the state's remaining farmland and forests are.)

Now, the news isn't all bad: the central cities of Hartford, Waterbury, New Haven, Bridgeport, and Stamford all grew in the last decade, consistent with the national trend of central-city recovery after years of decline. But only New Haven's growth rate equaled the state's average (Stamford came close). So there may be a baby trend to build on if the state and private sector want to get on board with the generational preference for more urban living. If they do, they will have a better chance of attracting and retaining young people with choices about where to live, and a better chance of prospering in the 21st-century economy.