Towards a More Resilient Relationship Between Cities and Water

Fifty percent of Americans live in coastal cities now threatened by extreme storms brought on by climate change, said AIA NY President Tomas Rossant at a recent event at the Center for Architecture in New York City. Architects, landscape architects, urban designers, and engineers need to collaborate to save our coastal cities. ASLA NY Chapter President Jennifer Nitzky, ASLA, said "effective resilience planning takes great collaboration."

Kicking-off the event, Stevens Institute of Technology professor Alan Blumberg and urban designer and professor Alexandros Washburn, Affil. ASLA, showcased their work at the new Center for Coastal Resilience and Urban Excellence (CRUX) modeling interactions of "water on cities and cities on water." Blumberg hope these models — if well communicated to the public — can help us better prepare for the next Sandy.

Communicating what we know is vital. One of the main issues during Sandy was researchers could predict where water would enter urban locations, but had trouble communicating this information to the public in advance. In Hoboken, New Jersey, which thought it was protected from the Hudson River swells, water would ultimately enter from the south and north. In one dramatic example, taxi companies seeking to evacuate to drier ground moved from an area where water would rise three feet to an area that would ultimately be submerged in nine feet of water, information Blumberg says he could have told them.

Can we use new technologies to communicate this information? What if we could check our Google Maps before a storm to see predicted conditions for a location and an overlay showing the range of water levels in street view?

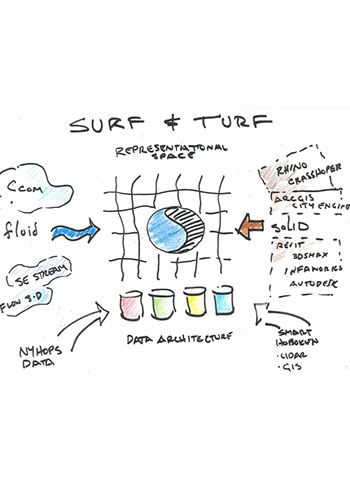

Washburn described the hybrid fluid-solid modeling he and Blumberg have been working on at CRUX. To date, software for fluid modeling and solid architectural modeling have existed in separate worlds. At CRUX, they seek to create hybrid "surf and turf" modeling programs to understand "how water affects the city and how the city affects the water, as well as ways to bring in data whether from fluid hydrological systems or topography and buildings to make the models comprehensible, accurate, and plausible."

"Surf and Turf" hybrid models would integrate fluid modeling software with architectural software / Alex Washburn / CRUX

Such models take grid-based software for fluid modeling and attempting to create fully three-dimensional grids. But such modeling needs to focus on specific locations since creating such grids requires tremendous computational power. Researchers need to understand where the hot spots are in the first place, then direct modeling efforts there. But Washburn believes things are looking bright with this technology: "Ten years ago, we couldn't even come close to modeling of this type. Now, we are at the edge of being able to define the problem and finding the solution."

Engineer Walter Meyer, founding partner, Local Office Landscape Architecture, presented several projects seeking to implement innovative and effective approaches to resilient coastal design. Meyer described the process of what Local Office calls "forensic ecology" to assess existing "nature-based features."

Meyer showed how wetlands could be used for "wave storage" and absorb water and energy from incoming waves, with the "potential to heal an entire bay and heal a coral reef." The type of wetland, however, is critical. Herbaceous wetlands, in one study, showed only a 13 percent effect on wave energy from storm surge, whereas woody wetlands, such as afforested mangroves in India, had a 50 percent effect on surge attenuation.

Meyer also showed how sand dunes are really "root" dunes and suggested ways to "horizontally turbo-charge" these dune structures to get similar functionality in narrow spaces such as the Rockaways.

"Forensic ecology" applied to several situations / Local Office

Planted "double" dunes "horizontally turbocharge" ecological functionality in narrow spaces / Local Office

Beyond wetlands and dunes, manipulating underwater topography could also have an impact on coastal resilience. Meyer used forensic ecology to explain how "Hudson Canyon," a gully in the sea floor just off the Rockaways in New York, correlated to hot spots of wave energy that caused further erosion. Such findings suggest that topography could be used to focus wave energy on particular hot spots of heavy impact on the coastline where more intensive infrastructure might be built to cost-effectively mitigate storm damage.

How can projects that use these novel approaches take root? Anthony Ciorra, US Army Corps of Engineers NY district chief of coastal restoration and special projects branch, said the Army Corps' has its hands tied to a great extent as it awaits funding approvals and marching orders from Congress, but there has been a shift in culture there in recent years. Ongoing studies are exploring more sustainable and adaptable solutions, and the Corps is trying to integrate resiliency thinking into its projects. That said, for the Army Corps financial feasibility is primary and "recreation is secondary . . . any project must first show that risk reduction choices equal a cost benefit."

The best approach, agreed on in theory by all presenters, is to find ways to collaborate regionally, across state lines and beyond election cycles. "Nothing happens in the city without aligning money, politics, and design," said Washburn, recalling something he learned while working with US Senator Daniel Patrick Moynahan. "And if you can't hold them together through an election cycle, it falls apart."

Washburn added that "nothing will help speed our preparation for the next storm more than our ability to make decisions better at the federal and state level and do something that America as a nation was not set up to do, which is to have politicians work regionally."

Yoshi Silverstein, Associate ASLA, is founder and lead designer-educator at Mitsui Design, focusing on landscape experience and connection to place. He was the ASLA summer 2014 communications intern.