Vancouver's medal-worthy Olympic Village, one of the greenest neighborhoods anywhere

Vancouver's civic leaders believe that the athlete's village built for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games, and the planned neighborhood that will surround it, will be one of the very greenest neighborhoods in North America. I am inclined to agree.

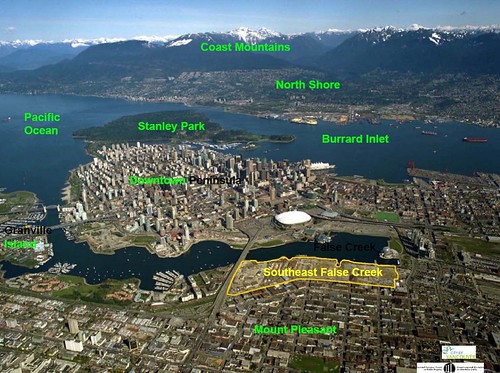

The village is the central parcel in a larger planned redevelopment of a section of the city's old industrial waterfront called, somewhat awkwardly, Southeast False Creek. When the Olympics and Paralympics are finished, the village will become a mixed-use community called Millennium Water, which sounds a lot more marketable to me.

I haven't visited the site, but I have sifted through virtual reams of information about it, and I have paid particular attention to its plans and progress for some time now because Southeast False Creek is participating in the LEED-ND pilot. (It hasn't been evaluated yet but the development is aiming for a gold level award.) The city's summary information sheet explains the project's goals:

"While maintaining heritage ties to the past, SEFC is being planned as a model sustainable development based on environmental, social and economic principles where people will live, work, play, and learn. SEFC will be a mixed-use community, with a focus on residential housing. This complete neighbourhood will ensure that goods and services are within walking distance and that housing and jobs are linked by transit."

The 80-acre site's mostly mid-rise buildings will provide ample density to support retail and walkability while still leaving 26 acres available for park land, including playgrounds and space for community gardening. There will also be an elementary school and new civic center. Some of the site's historic buildings (notably including the Salt Building, shown in the photos) will be preserved, along with other reminders of its historic past. Transportation options will include rapid transit, a "skytrain," a streetcar, multiple bus lines, three new greenways with cycling facilities and, of course, a pedestrian-friendly atmosphere. The site also needed and received extensive brownfield remediation.

Most of the development's buildings will qualify for a LEED-gold building certification (in addition to the LEED-ND goal for the project as a whole). One of them has been designated as a "net zero" building that will have no net carbon emissions. It will be converted to 64 homes for seniors after the Games. And the developer is aiming for a LEED-platinum rating for the community center that will be the village's focal point during the Games and the most publicly visible of the neighborhood's buildings afterward.

Southeast False Creek/Millennium Water will also sport the city's first renewable district heating system, which will provide heat and hot water to all the neighborhood's buildings, including those in the Olympic village. It will be the first time in North America that heat recovered from wastewater will provide a primary source of energy for an urban neighborhood. The wastewater technology will be supplemented by solar hot water.

The city began planning development of the site in 1997 and committed to a vision of sustainability in 1999. Eventually it will be home to 16,000 residents. Close to 3,000 will be housed there for the Games.

The environmental accomplishments and goals of the Olympic village (officially Village A, since there is a second athlete's Village B in Whistler, BC, where downhill events are being held) are summarized in an overview on the Olympics' official site. In addition to those mentioned above, they include ecological restoration of the waterfront; reintroduction of intertidal marine habitat and indigenous vegetation, and extensive green stormwater infrastructure. As shown in the images, most of the buildings will have green roofs. Other laudable elements include accessible design, job training and procurement for inner-city residents, and impressive (and sustainable) public art, including traditional and contemporary works by Inuit, Métis, and other First Nations indigenous artists from across Canada.

The village's sustainability features are seen by the Games as part of a larger goal of sustainability throughout the Olympic venues and events, and by the city as consistent with its' leaders vision of becoming "the world's greenest city."

As with any large development, especially infill and especially one receiving subsidies in the context of a recession, the project has not been without controversy. This is well-documented on the Web and was succinctly summarized by Jonathan Hiskes on Grist. The project was planned to be financed largely by Millennium Water's investors and recouped by them after the Games as its units were sold. But a major source of the developer's capital collapsed with other financial institutions and the city had to come to the project's financial rescue (to be repaid when the development sells). There were also the usual construction problems and cost overruns. The financial squeeze meant that, unfortunately, some of the project's Phase I affordable housing had to be scaled back. In addition, some Vancouverites have long resisted the idea of the city's hosting the Games at all, and the village became a bit of a rallying point for the opposition.

But now the village has been completed and was handed over to the city on schedule, in November. It has received glowing reviews not just from environmental writers but also from real estate observers who believe Millennium Water will be a huge commercial success when it is handed back to the developer (see, for example, here and here). Based on what we can see, that's hard to argue with. I can't wait to see it for myself.

Here are two really good videos about the project. The first models the development's progress from start to finish with very cool animation, and has an awesome soundtrack. (Someone please tell me who that is; if you prefer Beethoven, by the way, go here.) And the second provides a montage of the project's construction with an excellent explanatory narrative and first-rate visual production. Highly recommended:

For a short commercial for Millennium Water, try this one. Let the Games begin!

Kaid Benfield writes (almost) daily about community, development, and the environment. For more posts, see his blog's home page.

Link to original post