When "Parking" Meant "Making Space for Trees"

In April, the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) and DeepRoot co-hosted a design charrette at the SvR offices in Seattle. The theme of the discussion was "Cities need nature, and nature needs cities: how and where do you struggle to bring nature to the built environment?" (We are putting together videos and blog posts based around the discussions from the day; stay tuned be notified when those are available.)

The motivation for the charrette was to better understand the challenges to integrating nature into cities at every stage in the process, from conception and design all the way through to construction and maintenance. A fantastic cross section of people attended, including members of LAF's Leadership Circle, as well as practitioners from the fields of engineering, arboriculture, academia, and more.

We had a rich discussion that extended beyond the concerns of any one discipline and into the broader realm of what makes for the most successful public spaces. One story that came up that day is from Michele Richmond, a site designer with Swift Company and the author of today's blog post about the history of the word "parking," and how it used to mean what it sounds like – a place for trees. -LM

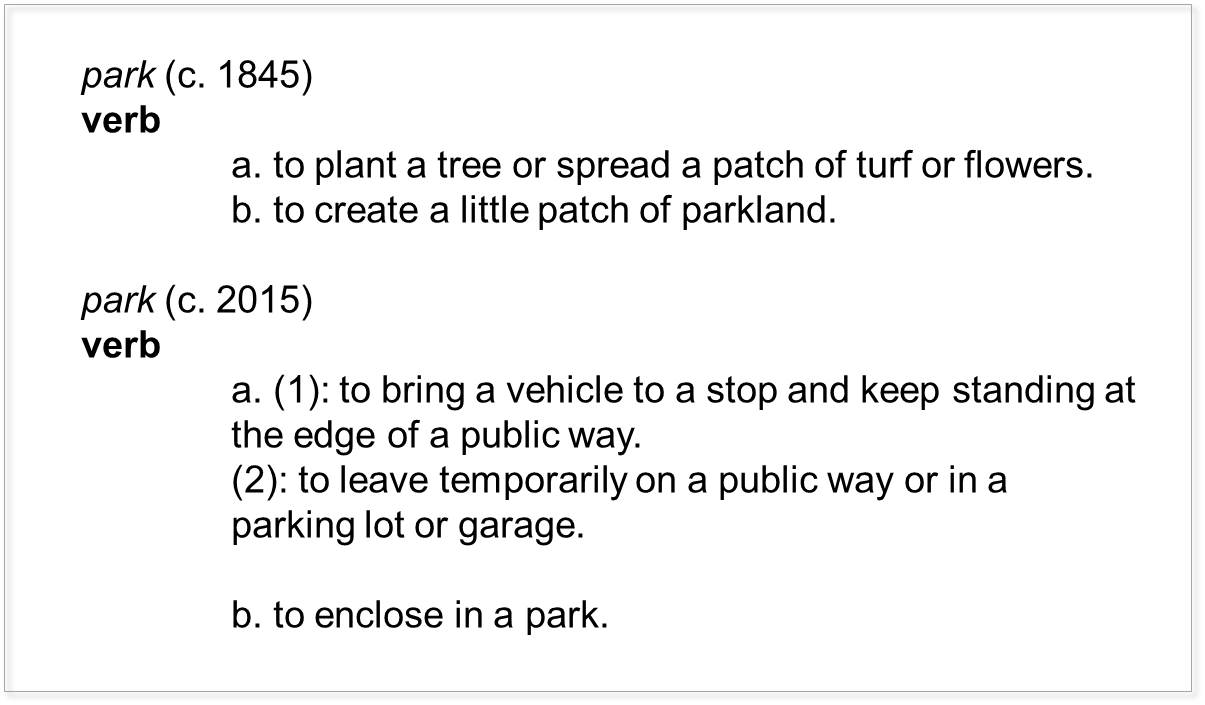

I've always wondered why we use the word parking to describe a place to leave a car. The word evokes images of my neighborhood park, playgrounds, or Central Park: lush green spaces not places easily reconciled with a patch of asphalt. A few years ago while I was working at the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, I finally got my answer.

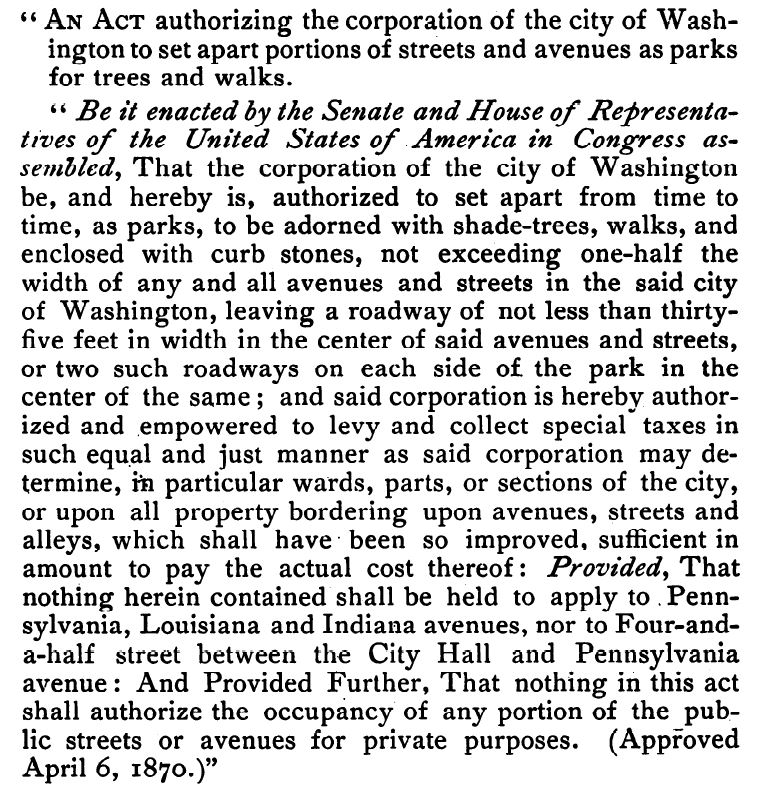

While exploring the history of street trees, I came upon a law passed by Congress on April 6, 1870 authorizing the city of Washington DC to set aside up to 50 percent of the width of a street for the creation of "parks for trees and walks". At that time, the Senate debated about the proper layout of the street, whether to have "the parking on either side of the street and the roadway in the center" or to have the "parking" in the center of the street.

According to the 41st Congress, the "proper" way to park in cities was on the side of the streets with the roadway running down the center. Of course in 1870, the members of the Senate were discussing the parking of trees, not automobiles. The first parking system was a street tree system where "parking" defined the planting of trees, grass, and flowers along the side of roadways and the creation of sidewalk for pedestrians.

An 1870 law put a 50 percent street width for parking (trees, that is!) into effect in Washington DC.

So how did the word "parking" come to refer to cars rather than trees?

Following the passing of this 1870 law, the Parking Commission of Washington DC (founded in 1871) immediately embarked on a massive campaign to create parking on all roads within the city. More than 70,000 trees were planted on the streets of Washington in the first decade of the campaign under the expert supervision of Truman Lanham (the first Superintendent of the Parking Commission), William R. Smith (Superintendent of the UnitedStates Botanical Garden), William Saunders (Superintendent of the Grounds of the Department of Agriculture), and John Saul (owner of a local tree nursery).

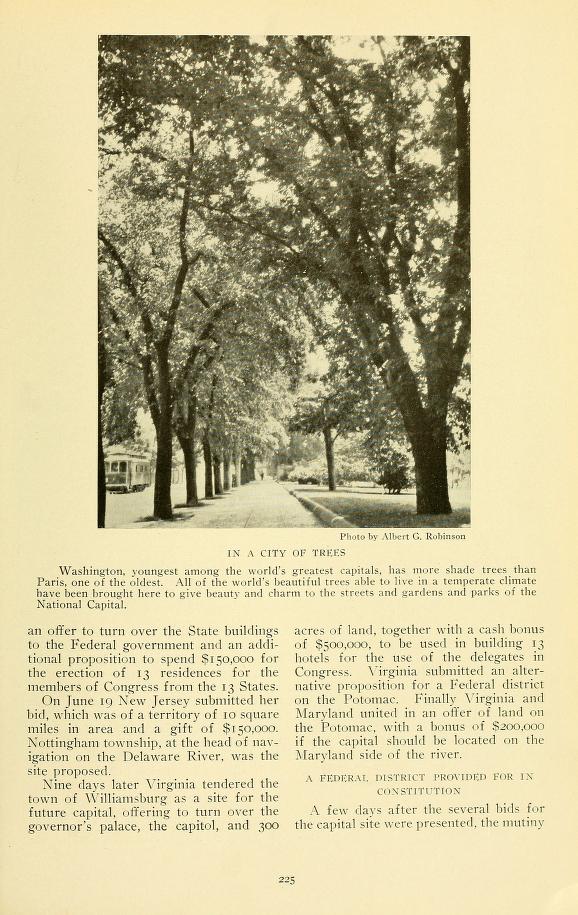

Until 1915, the trees for the streets were grown in a nursery on the grounds of the Washington Asylum. This allowed the Parking Commission to control the quality and diversity of trees that were planted in parking places, which resulted in a 95 percent tree survival rate 12 years after the initial plantings. By the mid 1880's, after almost two decades of tree growth, Century Illustrated Magazine reported that "in this matter of trees, Washington is unrivaled among all the cities of the world."

At first, citizens would place wooden boxes around the trees to protect them, but with the passage of another congressional law placing the jurisdiction of parking places squarely in the hands of the Commissioners of Washington D.C., this practice was soon discarded.

Page from a 1915 article in National Geographic Magazine written by former President William Taft. He writes, "Washington, youngest among the world's greatest capitals, has more shade trees than Paris, one of the oldest. "

This new law had unintended consequences: the removal of the protective boxes allowed people to wedge their way into the parking system. How? Because during the hot summers in Washington, trees provided shade for horses while their owners were off in a shop or visiting a friend. Owners would tie their horses (and carriages) up to the street trees, effectively decreasing a two-lane road to one active lane and one stopped lane. While it became illegal in 1882 to trespass on parking, or to cut, injure, or maim parking trees in any way, the convenience and shade provided by the trees for the waiting carriages and horses outweighed the fine levied.

The world was changing rapidly. Automobiles increased in number from 8,000 in 1900 to over 8 million in 1920 and marked a major shift in the meaning of the term parking. Just as people would tie their horses to the parking trees, automobiles began to stop next to the parking strips lining each road. The increase in the number of automobiles on the road, the enhancements made to the National Mall, and the See America First tourist campaign (beginning in 1910), led to a huge increase in the number of cars in Washington DC from both locals and tourists.

Of course, the Washington DC Parking Commission had not planned for the automobile when setting out their parking system. By the mid-1920's city officials began cutting down street trees and widening streets to accommodate the volume of cars, literally and figuratively replacing the original parking as a place for trees and greenery with parking as a place for automobiles to stop. Some of the earliest instances of this shift appear in Washington Post articles from the 1920's, where the term "parking" was used to explain where cars were parked rather than to where trees were planted.

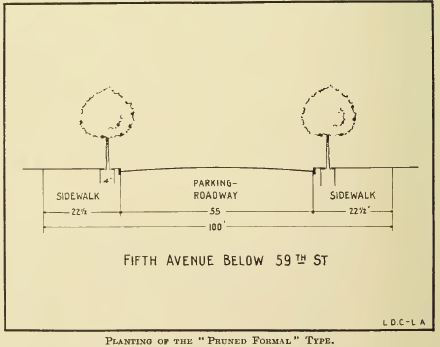

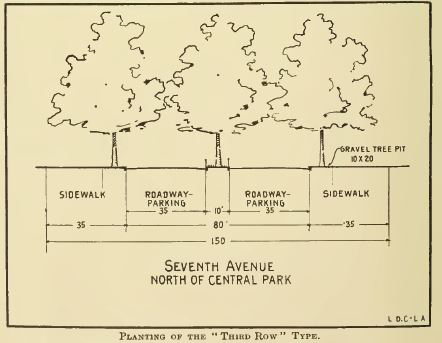

A proposed cross section for a New York City Street from Laurie Davidson Cox's "A Street Tree System for New York City, Borough of Manhattan"

A proposed cross section for a New York City Street from Laurie Davidson Cox's "A Street Tree System for New York City, Borough of Manhattan"

Washington DC was the first city to implement a street tree system, yet the sea change in the meaning of parking happened quickly. As such, by the time other cities began to implement similar systems (chiefly New York City in 1916), the term parking was already referring to cars much more often than it was referring to roadside vegetation. Before long, the shift was appearing in design texts like Laurie Davidson Cox's "A Street Tree System for New York City, Borough of Manhattan" where a typical cross section of a street has a sidewalk, a street tree, parking (for an automobile), the roadway, parking (for another automobile), a street tree, and sidewalk.

The public expects amenities on the street such as shade provided by trees, places to leave their carriages and cars, and safe places to walk. These expectations shifted significantly in the first few decades of the twentieth century as needs changed. Throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, these needs evolved and the relationships in the streets between trees, people, transit, businesses, and vehicles continued to shift. The arrival of the car as the main mode of transportation necessitated a shift in the amenities of the public right of way, favoring car parking over tree parking in the 1910's and 1920's. However, car parking may not always have a place of utility along roadways. We should reference this historic definition of parking and reinvent it for the future. As we shift rapidly towards better public transit infrastructure, complete streets, and walkable cities, it's time to rethink what the "parking" amenity is — and reinvent what it could be.

References

Cox, Laurie Davidson. A Street Tree System for New York City, Borough of Manhattan. Report to Honorable Cabot Ward, Commissioner of Parks, Boroughs of Manhattan and Richmond, New York City. Syracuse: U, 1916.

"District Downtown Storage Garage Is New Parking Plan." Washington Post[Washington, D. C.] 8 Aug. 1924: 4.

The Legislative Assembly of the District of Columbia (June 20, 1872) (enacted). Print. An Act for the protection of parks in streets and avenues.

"May Dance in Comfort." Washington Post [Washington, D. C.] 13 Feb. 1901: 10.

"The New Washington." Century Illustrated Magazine Mar. 1884.5: 648-651.

"Parking Commission." Minutes of the Board of September 4, 1871. Proc. of Board of Public Works, Washington D. C.

Savage, Kirk. Monument Wars: Washington, D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape. Berkeley: U of California, 2009.

Scott, Pamela. "The City of Living Green: An Introduction to Washington's Street Trees." Washington History 18.1-2 (2006): 26-31.

Tindall, William. "The Originals of the Parking System of This City." Records of the Columbia Historical Society 4 (1901): 75-99. JSTOR.Web. 07 May 2013.

"Use of Public Space for Parking Cited." Washington Post [Washington, D. C.] 13 Feb. 1927: 16.

Michele Richmond is a site designer with Swift Company.

Top image: Horse-drawn carriages tied up in "parking" lanes in Washington DC c. 1880 / Source: Curator's private collection / via Vanished Washington