Why Urban Demographers are Right About the Trend Toward Downtowns and Walkable Suburbs

I and others have been tracking for some time a surging interest in walkable neighborhoods, in both reinvested downtowns and more pedestrian-friendly suburban developments. Just last month I cited University of Utah Professor Arthur C. Nelson for the propositions that, contrary to what occurred in previous generations, half of all new housing demand between now and 2040 will be for attached homes, the other half for small-lot homes. The demand for large-lot suburbia, by contrast, is diminishing.

In other words, there’s a reason why city living is becoming more expensive and suburbs lass so: demand for what cities offer is up, and demand for automobile-dependent suburbs, relatively speaking, is down.

In my new book People Habitat: 25 Ways to Think About Greener, Healthier Cities, I put it this way in a chapter titled “But the Past Is Not the Future”:

“The way households are going to be evolving over the next few decades is toward more singles, empty-nesters, and city-lovers, none of whom particularly want the big yards and long commutes they may have grown up with as kids. A significant market for those things will still exist, but it will be a smaller portion of overall housing demand than it used to be. This new reality means that the communities and businesses that take account of these emerging preferences for smaller homes and lots and more walkable neighborhoods will be the ones that are most successful.”

The voice of a skeptic

Alan Mallach, a serious scholar at the National Housing Institute (NHI) and someone I respect, isn’t buying it, however. Or maybe he is, but only a little bit. Mallach believes that we may be seeing a short-lived phenomenon of latte-sipping Millennials moving downtown, but no one else, and even the Millennials may be unlikely to remain once they start raising kids.

On Rooflines, the NHI’s blog, Mallach cities suburbanist Joel Kotkin with approval and opines:

“As I read much of what is being written about demographic change and urban revival, I see a lot of urbanist wishful thinking, along the same lines as the scenarios some pundits paint of exurban McMansions turning into slums and squatter colonies, as their former residents flee the suburbs for the cities like the residents of Pompeii fleeing the eruption of Vesuvius. Is it possible? Yes, but the evidence is not there.”

Mallach may have a point when he sets up the easy-to-knock straw man of McMansions becoming squatter colonies. I think they will decrease in value, but squatter colonies is going a bit far. Nonetheless, I think he’s wrong to be so sharply dismissive of the evidence that weighs in favor of a lasting rebirth of central cities. (I’ll discuss some of the evidence below.)

He’s also wrong not to acknowledge that, while some residents will indeed prefer suburbs in future decades, that does not mean they will prefer the types of unwalkable, outer suburbs that we built in the last half of the 21st century. I believe that suburbs are here to stay but that increasingly they, too, will take a more walkable, somewhat less auto-dependent form.

The question whether the rebirth of cities will grow to include families is trickier. Here’s what Mallach has to say on the subject:

“The other question is whether millennials will stay in the cities as they move into marriage and child-rearing—as most will—and the appeal of all those bars and restaurants down the block begins to pall. If, as preference surveys show, most will ultimately look for a single-family house in which to raise their children, will they opt for a Philadelphia row house or a St. Louis Victorian, or will they move to the suburbs?

“It will be a while before we have a clear picture, but there is little evidence to point to a long-term millennial commitment to cities as a place to remain, settle down and raise families. Joel Kotkin not unreasonably chastises writers who, with little or no evidence to back them up, confidently assume that they will do so. While the jury is still out, there is no compelling evidence of anything resembling the fundamental shift in values and attitudes on the part of millennials that would lead to most of them behaving that differently from earlier generations, and—to the extent that their means permit—buying suburban houses in which to raise their children, and, as often as not, commuting to work in the city in their Priuses.”

Mallach’s cheap shot at Priuses aside, I have raised the same issue about whether we will make our reborn cities more family-friendly for those with a choice about where to live. I don’t think we have gone far enough yet to do so, but I am hopeful that we will, as those families with a preference for urban living begin to demand it.

More to the point, though, I wonder if Mallach is asking the right questions: I don’t see the fundamental future choice as between city and suburb but between more walkable, diverse and healthy places, on the one hand, and more automobile-dependent, monolithic, and unhealthy ones, on the other. As I also write in People Habitat, whether those places are within or outside city limits is of most relevance to cartographers and candidates for city office; the environment, economy and, increasingly, our social fabric don’t care. What matters in the 21st century is not so much “cities” in the traditional jurisdictional sense, but metropolitan regions and neighborhoods. Both are changing for the better, and in a lasting way, in my humble opinion.

Here’s some evidence:

Peak sprawl

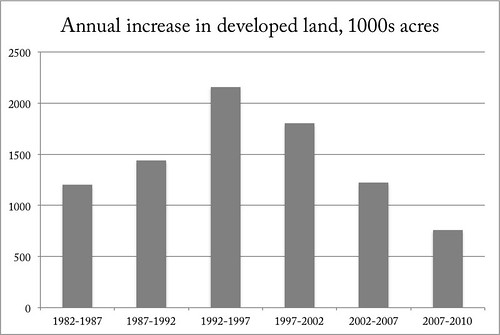

The rampage of sprawling, outer metropolitan development that ate up farmland while severely disinvesting older communities hit its peak in the mid-1990s, and there is no evidence that it is coming back. My friend Payton Chung, writing in his provocative blog west north, charts the amount of land converted to development over time. His graph, based on the National Resources Inventory, shows a dramatic rise in sprawl from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, followed by a marked decrease every five years since:

Note that the dropoff in the amount of newly developed land began a full decade before the recession and, for that matter, even before the “giant housing bubble showered suburbs with seemingly limitless sums of capital,” as Payton puts it. This decrease in outer suburban development isn’t “urbanist wishful thinking”: it is fact. It’s also fact that central cities are growing again, after decades of decline – and, for the first time in a century, growing at a faster rate than their suburbs.

The trend is also consistent with my own observations about average housing prices, which I charted and mapped for the Washington DC area during the recession years 2006-2009, and for the three following years, 2009-2012. The maps show a wide disparity between the changes in many outer location prices, which fell precipitously, and the prices in many inner and transit-served locations, which held steady or increased in value. I’ve seen maps of other regions that, to varying degrees, show similar results: urban housing values are proving more resilient than outer suburban ones.

As for what preference surveys say about the desires of the Millennial generation, those that I have seen support Mallach’s assertion to the extent that some Millennials will seek single-family homes and suburban living. But not to the same degree as preceding generations. According to analysis by industry advisers RCLCO, 31 percent of Millennials prefer a “core city.” What is particularly significant about this finding is that it is twice the portion of the preceding generation when polled at the same age. Perhaps more to the point, two-thirds wish to live in walkable places and town centers, whether in the inner city or in suburbs. A third will pay more for walkability, and half will trade space for it.

Professor Nelson, cited above, believes that, although there will be a continuing demand for large-lot housing, that demand will constitute only 25 percent of the market by 2040. Seventy-five percent will seek either attached or small-lot housing. This makes particular sense when one considers that the number of adults of child-rearing age and the number of households actually living with children will comprise a much smaller portion of the overall market than in previous decades. Nelson estimates that 87 percent of the growth in the housing market through 2040 will comprise households without children.

This means that, even if Mallach is right in his predictive generalization that today’s loft-dwelling Millennials will become tomorrow’s auto-dependent suburbanites – and I don’t believe there is evidence that the generation will make such uniform choices – there will still be plenty of people in the market for urban and walkable suburban homes. And, yes, some of them will be empty-nesting seniors who must or prefer to reduce their driving. While many will remain in their current, automobile-dependent suburban homes until forced out by infirmity – I have sad personal experience with this – I believe that many of those who do move will choose walkable environments as their new communities.

By the way, it isn’t just current and future residents who are going to be choosing cities and retrofitted suburbs over the coming decades. After decades of fleeing downtowns for office parks and exurban campuses, corporations are moving back to the city, too, such as Motorola in Chicago (3,000 jobs coming back to the Loop) and the other large businesses I cited in December. Meanwhile, the major corporations in Dublin, Ohio – the wealthiest suburb of Columbus – have banded together with city leaders in a major, multi-year effort to make their sprawling community’s business district more walkable and hospitable to the bright young talent they need to recruit.

Peak car

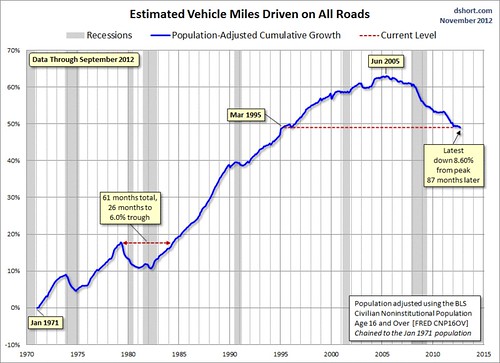

It took a while to convince me of this one, but the data show that we have also hit a peak in vehicle miles traveled (VMT), on both a per capita and absolute basis. I believe the following graph shows the population-adjusted total rate of driving (something akin to VMT per capita but not quite the same; see the technical explanation):

The graph shows that VMT in the US peaked in 2005 and has been dropping ever since. Note again that the beginning of the decline preceded the recession – and the drop has been continuing steadily throughout the recovery, to the point where by late 2012 population-adjusted driving had decreased to 1995 levels.

In the same article in which he discusses the decline in the rate of newly developed land, Payton Chung speculates – and I suspect he is right – that the primary reason for the decline in driving is that, as regions have stopped spatially expanding, driving distances have gotten shorter, on average, as they have added population. Other reasons include mode shifts as greater portions of the population are able to choose walking and public transit for a portion or all of their trips.

Writing last year in The Atlantic Cities, Emily Badger summarized the data:

“The handy thing about ‘peak car’ as a concept is that it can nominally be proven in many ways. You’ve got Peak Driver’s License. Peak Registered Vehicle. Peak Gas Consumption. Peak Miles Traveled. There are peaks per person, per household, per demographic. Then you’ve got your absolute peaks when you add up all of our vehicles and miles together, as if we were all cruising the highways at the same time.

“Earlier this summer, [University of Michigan researcher Michael] Sivak released data showing that the number of registered light-duty vehicles in America (cars, pickup trucks, SUVs, vans) had peaked per person, per licensed driver and per household in the early to mid 2000s, before the onset of the recession. Because the U.S. population continues to grow, he predicted that the absolute number of vehicles had not yet peaked. But per person and household, we seem willing now to own fewer of the things . . .

“All of the peaks on [Sivak’s] chart occur around 2004, a time that predates both the recession and the housing bust. That means, Sivak suggests, that other factors beyond the temporary state of the economy may be driving these downward trends, from the rise of telecommuting, urbanization and public transit usage to fundamental shifts in the age demographics of drivers.”

Before she stepped down as director of planning for Washington, DC, Harriet Tregoning told me that, in the previous decade, the city had added 15,000 residents with no net increase in driver’s licensing or registered vehicles. I find that astonishing evidence that something real is going on.

Again, this is not urbanist wishful thinking. These are facts.

I suppose Mallach’s answer might be that, once the Millennials start having those kids in the suburbs, we can expect driving to grow again, whether in Priuses or not. And he may well be right to a degree, but I’m betting it won’t be to a degree that takes us back to the per-household levels of 2005.

Consider that, over the last decade, miles driven by Americans aged 16 through 34 dropped 40 percent per capita compared to the same age group in the previous decade. That’s not evidence of a real change? In the same decade, bicycling trips per person in the age group went up 24 percent while walking went up 16 percent. Twenty-six percent of Americans in that age group, a growing number, do not have a driver’s license. (Sorry, but that’s a huge change: the most exciting day of my young life at age 16 was the day I got my driver’s license.)

Again, we don’t need a wholesale shift in behavior to indicate a shift in direction. And I suppose that is my biggest beef with Mallach’s argument: it presents only two options, either that Millennials are choosing cities for the long haul, or they going to revert to 1980s-style suburbia. I suspect the truth is in between, but that a larger portion of Millennials will stay in cities or choose walkable, 21st-century suburban places than did previous generations.

Peak Walmart?

One can even make a case that we have reached a sort of “peak Walmart,” in which the decades-old business model of the giant retailer – paving over forests and farms at the exurban fringe to establish automobile-dependent megastores – is past its prime. The company’s fourth-quarter net income for 2014 fell 21 percent. And, although Walmart isn’t saying it in so many words, the retailer believes its future lies in a different, less sprawling and more urban direction.

Writing in last Friday’s Washington Post, Amrita Jayakumar reports:

“In its fourth-quarter earnings report, Wal-Mart said sales at its U.S. stores fell 0.4 percent and customer traffic decreased 1.7 percent. But the company’s global e-commerce sales grew to more than $10 billion in 2013, an increase of 30 percent from the year before. Sales at its small stores were also up 4 percent in the last year.

“Wal-Mart said it would pour resources into online and mobile shopping options. The retailer also announced that it would open twice as many neighborhood stores throughout the country.″ (Emphasis added.)

Over on his Strong Towns Blog, my friend Chuck Marohn quoted a story from CNBC on Walmart:

“The big-box discounter is in need of a bricks-and-mortar makeover, analysts said. To resonate with today’s shopper, Wal-Mart needs to move its stores closer to major population centers, shrink the square footage of its superstores and shutter about 100 underperforming U.S. locations, they suggest.”

In other words, Walmart needs to move away from sprawl, because that isn’t where the future market potential lies.

Not that closing and abandoning suburban Walmarts – leaving communities with 20-acre decaying eyesores that are difficult to repurpose – is such a great thing, by the way, even if it does furnish further proof that land use in America is fundamentally changing. And, as for Walmart’s “going urban,” that may not be such a great thing, either, as discount competition drives out established businesses that have made longstanding commitments to inner cities.

A more serious issue

Toward the end of his article, Mallach – whose scholarship has focused heavily on weak-market cities and neighborhoods – raises what I believe is his real concern: not that cities and the geographies of living patterns aren’t fundamentally changing, but that they are; and the changes don’t benefit lower-income populations.

That’s shifting the subject from where he started, but it’s a legitimate issue and a serious one. In some inner cities (in the Rust Belt, for example) the comeback is going to be far slower than in others; in some neighborhoods the influx of newer urbanites could have no positive effect or even negative effects on pre-existing residents. A trend toward walkable suburbs may indeed represent an indication that the Millennial generation has a different set of lifestyle preferences than its predecessors; but it is probably irrelevant to most inner-city, lower-income residents.

I do have a more favorable view than does Mallach of the prospects for older city neighborhoods to reverse years of abandonment and disinvestment to come back. I believe much more than he does that Millennials have a stronger inclination toward urban living than did their predecessors. I think the effects will be lasting.

But I share Mallach’s concern that the current brand of city recovery hasn’t come close to solving the problems that plague poor inner-city residents, including bad schools, chronic unemployment, higher crime rates, and poor health, just to name a few. Smart growth, urbanism, and changing generational values may be real, but they don’t address those social problems. Neither does much else, as far as I can tell: Very little that has been tried over the past several decades has had a pronounced, lasting impact to lift people out of poverty.

That may be tragic, but for me it doesn’t warrant a wholesale dismissal of the many good things going on in cities and metropolitan regions today. It just underscores that we haven’t figured out how to solve some deeply embedded social and economic problems.

I wish I had the answers. I don’t, and as far as I can tell no one else does, either.