Emergency response management is a high-stakes space. Each decision can mean life or death, which makes training and preparing for these scenarios critical.

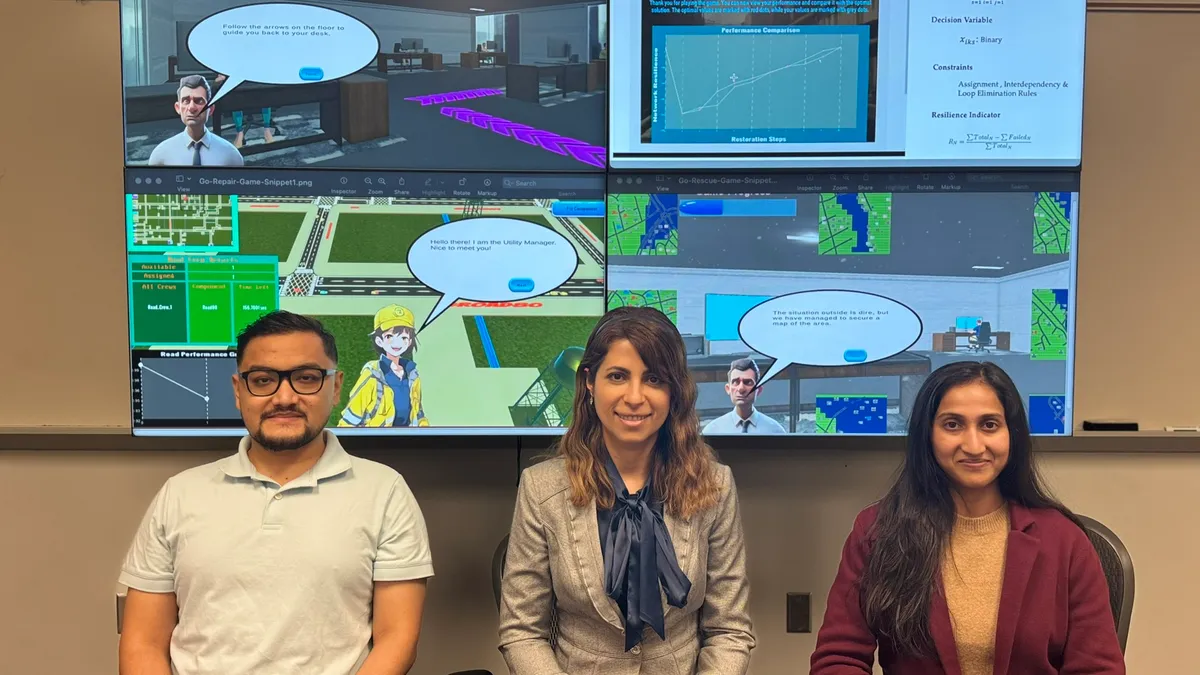

Over the course of a year, a three-person team from George Mason University worked to improve preparedness via AI-powered games for the Department of Public Safety Communications and Emergency Management in Arlington, Virginia.

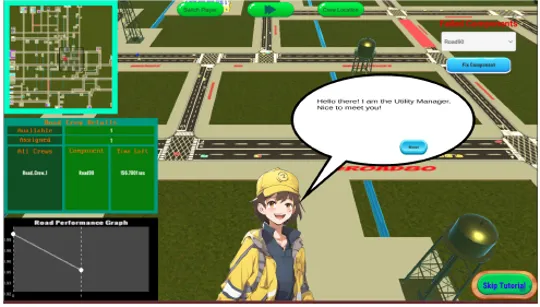

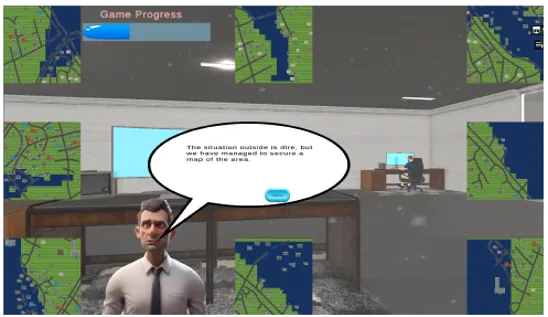

Using an iterative process and feedback from Arlington County department members, the team created two interactive games, called Go-Repair and Go-Rescue, which simulated infrastructure maintenance, resource allocation and evacuations. The dynamic learning environment provided utility managers and volunteers with a wider scope and more flexibility than traditional training methods.

“AI optimization and reinforcement learning models calculate the optimal decisions, and this allows players to assess whether their decisions are better or worse comparatively,” said Shima Mohebbi, assistant professor in the Department of Systems Engineering and Operations Research at GMU and the project’s leader.

Incorporating AI into training enables the department to better identify areas of improvement in decision-making and provides a tool to learn from mistakes without real-world consequences. To avoid subjectivity often seen in large language models, the researchers developed a model with a mathematical foundation and used reinforcement learning.

Enterprises can also gain value from incorporating AI into training and workforce development, from adaptive learning platforms to AI-augmented skills assessments. More than 3 in 5 HR pros expect AI to wholly transform the way training is currently conducted, according to a survey by management consulting firm OC&C Strategy Consultants. Most respondents said they were looking to expand AI adoption to talent management.

To infuse AI into training, business leaders can choose off-the-shelf options. Most corporate training providers, including Coursera, Skillsoft and LinkedIn Learning, have added the technology to their tech stacks to some degree, and CIOs can also look into developing in-house solutions.

Mohebbi said leaders interested in developing a similar solution to Go-Repair and Go-Rescue should start by getting a clear understanding of the problem they want to address. To do that, Mohebbi’s team focused on connecting with stakeholders.

AI model decisions

Despite the current spike in interest regarding generative AI, Mohebbi’s team didn’t pursue that particular branch of artificial intelligence.

“The AI models that we are using are based on a mathematical foundation, not just generated based on past experiences,” Mohebbi said. “We really need to have that strong mathematical foundation to avoid the subjectivity we usually see in large language models.”

Hype alone isn’t enough to warrant implementation.

CIOs have had to work to rein in generative AI use cases and prioritize those with the most potential. The costly technology is not the best or most reliable tool in every situation.

“We want to look at AI, which is not a hammer looking for a nail, but [by being] clear in terms of what’s the business problem or context we are solving and how can AI enable us to do that,” Surabhi Pokhriyal, chief digital growth officer at Church & Dwight, said during the company’s analyst day last week.

Technology leaders who tease out generative AI’s weaknesses and lean on its strengths to prioritize use cases find success. Oftentimes that means fewer deployments. Leading organizations pursue about half as many generative AI opportunities on average compared to less advanced businesses, according to Boston Consulting Group.

As the GMU project developed, stakeholders raised questions about the reliability of the AI models used to power the training games.

“We added more information about these background algorithms,” Mohebbi said. “They were more comfortable afterward and enthusiastic about adopting the game.”

Implementing stakeholder feedback

Go-Repair and Go-Rescue function quite differently than they did initially. Mohebbi’s team created several versions before landing on the current functionality and capabilities.

“We held meetings and then provided a version and they would test it out and provide us with feedback,” Mohebbi said. “We’d address their feedback and provide them with an updated version. It was a very iterative process.”

One of the first changes was also the biggest. The game was initially designed to be played offline, but security protocols within the department wouldn’t allow downloads. Mohebbi’s team then shifted to web-based development.

Mohebbi’s team also added visual elements, improved user experience, enhanced the localized scenarios and provided more insight into user decisions and their consequences throughout the process.

The partnership between technologists and end users was crucial to the project’s success.

“If it wasn’t for the feedback and our interactions with Arlington County, we wouldn’t even know about the certain specifics and features needed,” Mohebbi said.