Uber slammed Toronto lawmakers last year when they side-stepped their own rules to limit ride-hailing licenses to 52,000 in what the company called a discriminatory and bad-faith effort to kneecap its business model.

“The City chose to ignore its own procedures and adopted the License Cap by ambush, without notice to Uber, other stakeholders or the public,” the company said in its Dec. 4 lawsuit against the city.

The Toronto City Council has since pulled back to take a more considered approach that includes getting public input, and the company has withdrawn its lawsuit. But other cities have likely taken notice and any efforts they make to curb the ride-hailing giant and its competitor, Lyft, are unlikely to provoke a direct battle with a company known for its brashness.

“Wherever Uber establishes operations, controversy soon follows,” Syracuse University Professor Austin Zwick, a public policy expert, told Legal Dive.

More likely, Zwick said, lawmakers that want to curb the companies’ impact on their cities will take a more indirect approach by regulating on climate and labor grounds.

Big impact

In October, the Toronto City Council met to vote on a bill that would require licensed drivers to use zero-emission vehicles by a certain date but before voting on that, lawmakers, in a surprise move led by Mayor Olivia Chow, brought up and passed a bill freezing ride-hailing licenses at 52,000, the level at the time.

Supporters of the bill claimed Uber was increasing street congestion and carbon emissions, paying below-minimum wage rates and putting the squeeze on taxi company revenues.

The arguments weren’t new. “If you look at whether there are more vehicles on the road, more congestion, and with that, more greenhouse gas emissions, the answer is clearly yes,” Zwick said.

Those kinds of impacts are why cities like San Francisco have not been happy about the presence of Uber, he said.

Also, the competitive impact on taxi companies has been clear for years.

“When it comes to a level playing field, Uber has the advantage,” Zwick said. “With taxi companies, many of the operators have paid huge amounts of money up front, and in places like New York City licenses can be hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

At the same time, wage differentials are an issue. Uber considers its drivers to be contract workers, so it’s difficult to apply minimum wage laws. “That’s the biggest area of regulation that’s an ongoing debate right now,” he said.

RideFairTO, a public advocacy group that supported Toronto’s effort to impose caps, added another element to the debate, claiming that unchecked growth of Uber is undermining public transit.

“By moving public transit users into thousands of individual cars, they are eroding transit authorities’ capacity to provide (and grow) an effective public transit network,” the group has written.

Furthermore, “Like other internet-based companies, ride-hailing platforms seem to play by their own rules,” the group said. “They extract value from our communities by using public infrastructure, but don’t pay anything back in taxes or decent jobs. They facilitate a race to the bottom that needs to stop.”

In its lawsuit, Uber said the effort to curb its growth only hurts people who need transit the most.

“At a time when local residents no longer have access to rapid transit, Mayor Olivia Chow’s arbitrary rideshare cap will negatively impact them the most,” the company said. “With fewer drivers on the road for the increased demand, wait times will increase and prices will go up.”

Widespread concern

Toronto isn’t the only North American city looking at legislative action to reduce the number of Uber cars on the road.

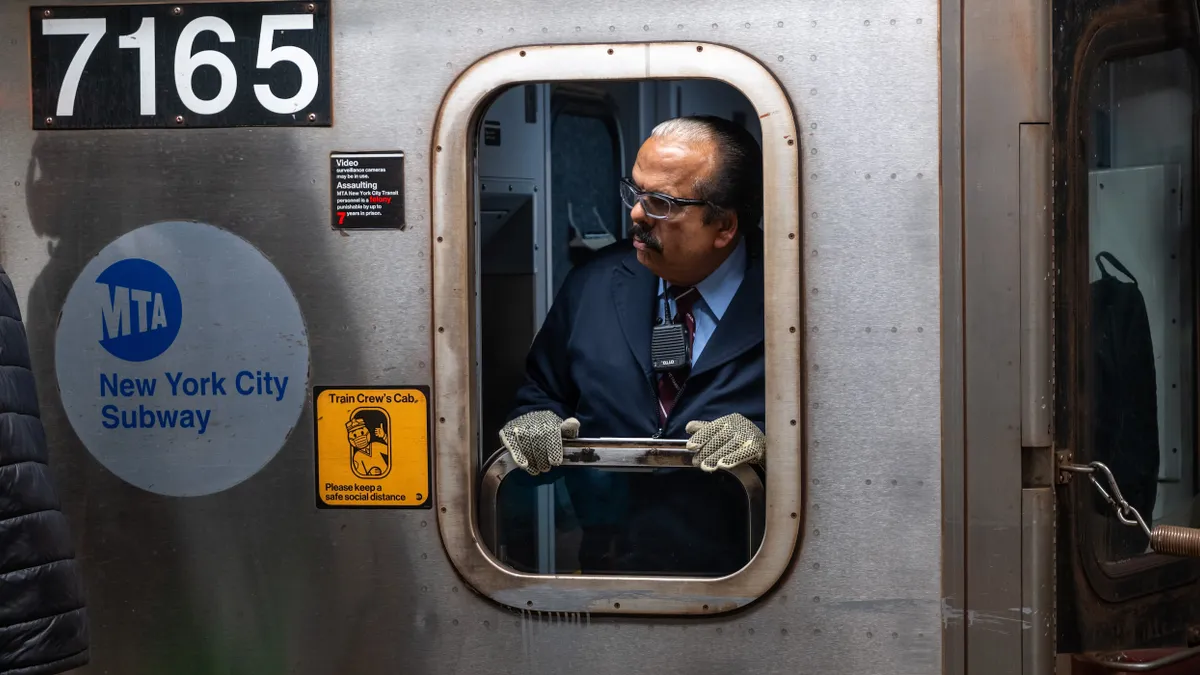

In New York, after much advocating by the Taxi and Limousine Commission, the city placed a cap on the number of ride-hailing cars. It has since rescinded that decision but has imposed other constraints.

In both New York City and California, all Uber and Lyft vehicles on the road must be electric by 2030. However, New York is no longer handing out licenses to new Uber drivers who have gas-driven cars. All new ride-hailing vehicles must also be handicapped accessible.

Whether the city of Toronto takes a similar means to an end remains to be seen. For the moment, the city has dropped the bill and Uber has withdrawn their legal action. However, it’s not likely that this is the last we’ve seen of Uber vs. Toronto.

According to Mayor Chow, Toronto will continue on its path to cap ride-hailing licenses, after a due process of public consultation. But the city can expect another fight.

“Putting a cap on the number of drivers pretty much prevents Uber from doing the constant churn of drivers inherent in their business model, so they’re going to be fighting this tooth and nail,” he said.

Zwick said caps on drivers is probably not the way American cities are going to curb ride-hailing. Rather, he expects more U.S. cities to address the climate and labor issues the companies raise by regulating greenhouse gas emissions on transportation-for-hire vehicles and imposing higher minimum wage for drivers.