Four U.S. cities were recognized Monday by Results for America and Bloomberg Philanthropies for their “exceptional” use of data to inform policy, allocate funding, improve services, evaluate programs and engage residents, according to a news release.

The cities newly certified through the What Works Cities Certification program are Dallas; Boise, Idaho; Issaquah, Washington; and Sugar Land, Texas, along with five cities in Latin America. These communities will join the 74 other cities that have accomplished certification since the program launched in 2017.

What makes the certified cities special is that they are putting practices into action, said Rochelle Haynes, managing director of What Works Cities Certification. “It's not just putting the data out there. It's not saying you have the dashboards, but it's ... saying how are we leveraging those to actually make decisions and decisions that connect to people,” she said.

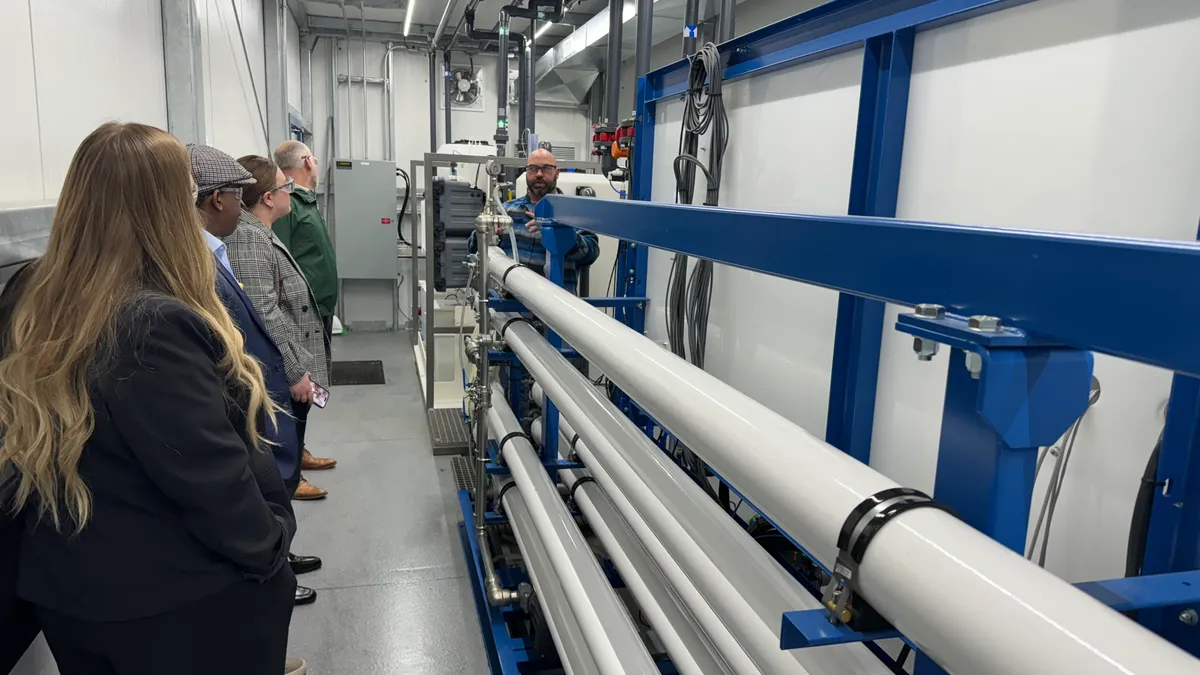

The newly certified communities used data in distinct ways. For example, Issaquah used data to connect those experiencing homelessness with resources and shared data with local businesses to help reduce burglaries and theft. Boise used data at dozens of community meetings to engage residents in its decision to build a new water treatment facility. Sugar Land analyzed population, housing and code violation data to develop a program that helped residents upgrade more than 166 homes.

Dallas combed through data to make budget decisions that address race- and income-based inequities, according to a news release. That led to $40 million in equity investments, the release says. “Now they're tracking that as well to see if those investments are actually getting the desired outcomes,” Haynes said.

How data-driven cities are evolving

Cities have significantly improved at using data to engage the public since What Works Cities launched, Haynes said.

“Gone are the days where you're a resident of a city and you don't know where to access information,” she said. “Open data portals are common. You have leadership routinely talking about data when they’re thinking about plans or programs that they're rolling out.”

Haynes said many cities could improve at using data to evaluate whether initiatives are working, which can be challenging due to lack of time and resources. “If I have a homeless prevention program, am I doing an evaluation to see if residents are actually staying in their homes because of the prevention services that we're providing?” she said. “Is it actually working, or are we just ... giving money to the problem and not actually solving for the upstream issue?”

Evaluation should be a consideration from the beginning of a project, not an afterthought, she said. Some cities even use their contracting requests for proposals to outline the outcomes they want to see.

It can also be challenging for cities to figure out how to align the many stakeholders involved in data-driven processes. Part of addressing that is determining who within an administration should be in charge of pulling together all the information to make strategic decisions, Haynes said.

Booming interest in artificial intelligence could also change how cities think about their data. “You have to be able to have the data to feed the AI tool,” Haynes said. “Cities have tons of data in different formats, so how do we help them think about organizing themselves to best use the technology?”

Among the cities Haynes works with, she sees the most excitement for AI around chatbots that can help residents connect with government services as well as to better understand traffic flow. Some cities are also using it for criminal justice applications, “but that's not across the board because of the questions around … bias and equity,” she said.