Maya Pindeus is co-founder and CEO at Humanising Autonomy, a predictive AI company that aims to facilitate natural interactions between autonomous systems and people.

Our cities are becoming more digital. The intention is to make life easier for the people who inhabit them — but is it working out like that?

Transportation in particular has seen a huge overhaul during COVID-19, with data analytics and automated systems introduced to make journeys more seamless for commuters.

However, most interactions are between people and surrounding infrastructure, not on busses or trains. Infrastructure is not passive — it’s a key player in ensuring equality in our cities, as referenced in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and the G20 focus on accessibility planning.

New tech can be hugely beneficial for our cities, but implementation without consideration can do more harm than good. In recent years, New York City’s LinkNYC Kiosks are an example. Introduced to make WiFi easily accessible to all members of the public, its lack of audible instructions and screen-reading functionality excluded blind communities. Though the American Federation of the Blind took action to correct the problem, it demonstrates a wider trend: city planners do not truly understand the needs of marginalized people.

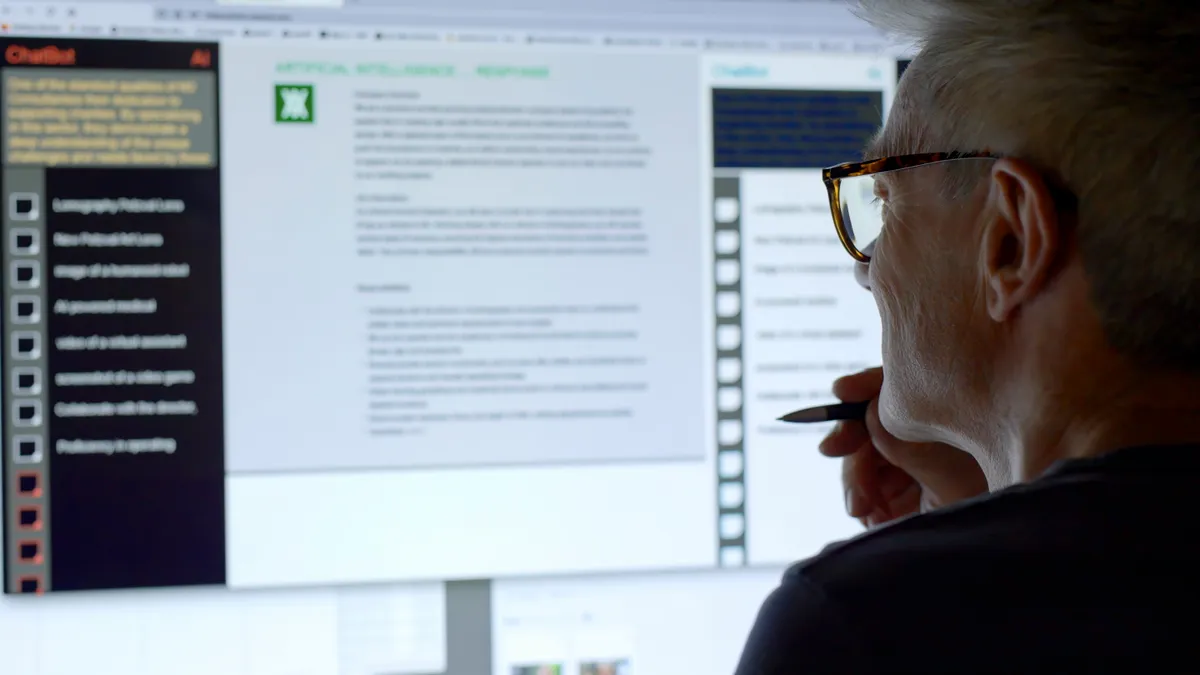

Artificial intelligence can ensure they do. With AI, municipalities can enable accessibility planning while upgrading infrastructure. Identifying behavior and accurately predicting intent of all pedestrians — regardless of environment, activity, culture or ability — enables truly inclusive, economically viable cities.

Infrastructure was built for the majority, not the marginalized

On the whole, city infrastructure was designed for the majority of people, without much consideration to differently abled pedestrians and road users.

Inclusive infrastructure is literally built differently.

Defined as any development that enhances positive outcomes in social inclusivity, inclusive infrastructure is essential to increasing social and demographic mobility. It’s an enabler: one statistic cites it as key to tap into the 249 billion euros in tied-up spending power of households with differently abled persons. It makes good business sense; more money in public transport systems means bigger budgets for the sector to innovate with. Ensuring that all persons have full access to work, healthcare and a social life is beneficial for the economy all around.

Still, most digital innovations perpetuate existing biases. Data-based decision making is insightful, but if the data is based on transportation hubs or cityscapes that exclude sections of society, it only serves to make problems worse.

Uber data used by the likes of Cincinnati’s Mobility Lab is one example of this problem. The partnership's intention was to use Uber data, which includes data on riders, ride-share pick-up and drop-off activity data, traffic count data, video documentation, and in-person observations, to help the city optimize planning, and identify ideal locations for businesses to expand and invest.

However, Uber data, as with any car-hailing service, is innately skewed. Over a quarter of U.S. riders have been previously recorded as being in the top income quartile, and a Gallup poll in 2018 found 41% of Uber and Lyft users made more than $90,000 a year. Meanwhile, studies have shown fares are higher when picking up or dropping off in areas with a higher proportion of non-white, low-income residents.

Isolated transit data has a history of enabling gentrification and the displacement of low-income households, especially when considering these groups are less likely to use ride-hailing services on the whole. Though the Cincinnati project does help city planners make informed decisions about where to invest, relying on an incomplete picture and biased data only perpetuates problems of inequality throughout the city. This is just one example of how transport data only captures one subset of society, and if gone unchecked, could continue to exclude minority groups.

Inclusive datasets mean that all behaviors are recognized, logged and considered when planning changes to infrastructure.

Inclusive innovation is efficient innovation

For cities, infrastructure maintenance and upgrades are some of the biggest financial expenditures to keep cities moving and economies growing. The International Transport Forum reported that the U.S., France, China, Germany and Sweden spent 98.8 trillion euros on infrastructure investment between 2010 to 2018; most of which was spent on standard maintenance costs. With so much resource being used on the day-to-day, cities must figure out how to keep costs low, while still innovating to speak to the needs of every individual.

In one case study originating a few years ago, the City of Jacksonville, Florida, deployed Numina sensors to address public safety for under-served populations. Estimates in recent years indicate people of color are 54% more likely to be hit by a car, while those over the age of 65 are 68% more likely to be killed in a road collision. With one of the highest pedestrian fatality rates in the U.S., the Jacksonville project protected marginalized groups that must resort to walking and biking out of necessity. The project has since been replicated in Las Vegas and St. Louis, bringing better insight into the use of roads for all people.

In the response to COVID-19, several European transit agencies have leveraged artificial intelligence to gain insight into how commuter behavior has changed during the pandemic, assess compliance with social distancing rules and regulations, and use this insight to optimize how transit hubs are designed. In Catalonia, Spain, an app developed by the Polytechnic University of Catalonia helps passengers navigate peak times by predicting the occupancy of buses throughout the day. Similarly, Belgium’s train infrastructure company Infrabel, is using AI analysis of camera footage to monitor social distancing and mask usage.

Municipalities and private sector companies must work in tandem to ensure the responsible deployment of automation anywhere for a safer, more productive way of living. Together, we can work toward an ethical society in which the value of inclusive infrastructure is measured by how well it promotes the safety and wellbeing of people.

Contributed pieces do not reflect an editorial position by Smart Cities Dive.

Do you have an opinion on a similar issue or another topic Smart Cities Dive is covering? Submit an op-ed.