The first time electrical engineer Johanna Mathieu heard about Ann Arbor, Michigan’s plan to create a “sustainable energy utility,” she thought it was crazy.

Even though investor-owned utility DTE Energy already provides the city’s electricity, Ann Arbor wants to set up its own supplemental utility that will initially focus on installing rooftop solar and battery storage at homes, businesses and other institutions citywide. Eventually, the plan calls for constructing microgrids to allow those buildings to share renewable energy across property boundaries, adding to the power lines that already crisscross the city.

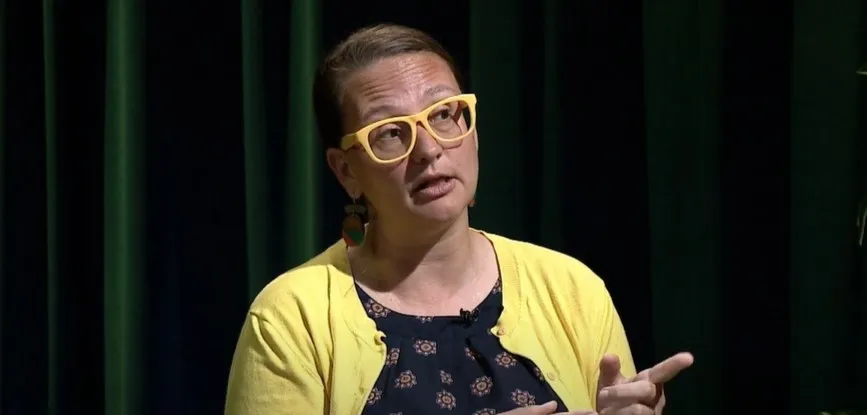

That idea of duplicating grid infrastructure goes against the most basic principles Mathieu teaches her students as an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of Michigan, she said.

“Power grid 101 is you don't build duplicate infrastructure because it doesn't scale,” Mathieu said. “That [infrastructure] should be owned and operated by a single company that's heavily regulated by a state or federal government.”

Voters in Ann Arbor, however, have decided the SEU makes sense: 79% of them voted on Nov. 5 to pass a ballot measure that authorizes the city to establish, construct, operate and own the new utility. The goal of the SEU, which officials hope to begin operating within the next two years, is to ramp up local clean energy generation and make the community’s electricity supply more resilient.

Here’s how the SEU will work when it first launches: It will pay the complete upfront cost of installing rooftop solar and battery storage systems at the homes, businesses and institutions of customers who choose to participate. The SEU will own and operate those systems forever and recover its investment over time by charging customers for the energy the rooftop solar panels generate, said Missy Stults, Ann Arbor’s director of sustainability and innovation.

When enough neighboring customers sign up for the SEU, the city wants to construct microgrids that let them share their renewable energy. That infrastructure would also allow the SEU customers to retain power even when the main DTE grid has outages.

The SEU will also offer programs to help customers pay for energy efficiency improvements, weatherization and electrification. Plus, it could operate community solar programs with solar power generated in shared spaces of the city and construct networked geothermal systems to heat and cool neighborhoods without burning fossil fuels on-site.

What differentiates the SEU from a standard municipal utility — besides only investing in local clean energy generation and decarbonization — is that it doesn’t seek to fully replace the existing utility. It aims to complement it, giving Ann Arbor residents more choices for where they get their energy. SEU customers will get one bill from the SEU and another from DTE for the energy they use from each supplier.

As the SEU adds more locally generated clean energy, the community will likely need less power from DTE. However, a 2023 report prepared for the city says it’s unlikely the SEU will fully replace DTE in the foreseeable future. Stults said in an email that modeling shows the SEU could one day provide more than 75% of the community’s total energy needs, but that outcome is unlikely to pan out “for a very, very long time as we’d need almost everyone in the City to sign up to meet that threshold.”

Mathieu, the electrical engineer, no longer thinks the SEU is a crazy idea. She now is collaborating with the city as a researcher on the project. Although the SEU may not be the most technically elegant model for energy infrastructure, it is the city’s best bet for quickly ramping up clean energy generation, she said. Other paths, like getting the existing utility to move faster toward clean energy or staging a municipal takeover of its infrastructure, aren’t realistic, she said.

“I've explained this to people like, ‘This is the fifth-best solution, but solutions one through four are not viable for a variety of different reasons,’” Mathieu said. “Five is feasible. So, let's do it.”

Seeking more control

The passage of the SEU ballot measure was a key moment in Ann Arbor’s years-long quest for more control over where its power comes from. The city’s climate goals include using 100% renewable energy citywide by 2030.

Some community members have pushed for the city to buy and take over the existing utility infrastructure through municipalization, but that could take years and cost Ann Arbor upwards of $1 billion. And municipalization efforts often face strong pushback from incumbent utilities, although they can give communities bargaining leverage to convince the utility to make concessions, like lower rates or clean energy commitments.

Others in Ann Arbor have advocated for Michigan to allow local governments to participate in community choice aggregation, which lets cities purchase renewable energy on behalf of residents while the existing utility continues to manage billing and distribution operations. State lawmakers have yet to pass such a law, which would likely face “strong opposition from incumbent utilities,” according to an FAQ document the city produced.

In 2021, “this idea emerged of, ‘Well, could we form a supplemental utility that doesn't focus on a takeover?’” Stults said. “Because, honestly … the goal wasn't to own the system. The goal was to generate clean, reliable, affordable power.”

Stults put together a small advisory task force of experts, who determined an SEU would be technically and economically feasible as well as legal under Michigan state law.

In some ways, Ann Arbor is following in the footsteps of Delaware and Washington, D.C., which have had versions of an SEU in place for years, but those differ from what Ann Arbor is planning, Stults said. Delaware’s SEU, for example, is a nonprofit that offers numerous programs to help home, business, nonprofit and farm owners access renewable energy and make energy efficiency upgrades, but it does not operate microgrids, according to John Byrne, president of the Foundation for Renewable Energy and Environment and a researcher who created the model for Delaware’s SEU.

How to start an SEU

Creating a new utility comes with startup costs, like hiring a director and setting up a billing system, Stults said. To avoid hoisting those costs onto a small number of initial customers, the city will wait to launch the SEU until its waitlist of potential subscribers hits 20 MW of demand annually.

Meeting the 20 MW threshold could look something like one or two large institutional partners or a thousand individual residents, Stults said. The city has been in talks with the public school system and other institutions about joining the SEU, and Stults said she expects quite a few to do so.

The picture shifts, however, if Ann Arbor finds grant funding, rather than taking on debt to fully finance the SEU. With grants in the picture, the SEU would need less demand to guarantee initial subscribers would see low rates, Stults said. She is also speaking with venture capitalists about investing in the SEU, and the city is budgeting $250,000 to $300,000 in existing funds to hire a director for the new utility.

The waitlist for the SEU, which the city began publicizing in October, had just over 650 names on it as of Dec. 4, Stults said, but she doesn’t yet know the exact demand that represents or if those are individual households, businesses or institutions. That information collection will likely begin in 2025.

The SEU’s final electricity rates will be “heavily influenced” by how many people sign up and what financing it gets, according to the city. Stults said the SEU will likely always be able to offer customers lower electricity rates than DTE can, in part because the SEU doesn’t have to generate profits for shareholders and can access capital with low interest rates, given the city’s AAA municipal credit rating.

Customers can join or leave the SEU at any time, although if they leave, the city will remove the infrastructure it owns from that building, Stults said. The cost of removing such infrastructure, along with the cost of equipment depreciation and replacement, will be built into the rates.

The SEU’s reliance on public buy-in is why the city put it on the Nov. 5 ballot, even though it could have gone ahead with the plan sans voter approval. “It’s a big deal to start your own utility, even a supplemental, opt-in utility,” Stults said. “This was the best way we could think of to confirm the public is seriously interested in this, even those who will never subscribe. Do they want more choice in the system?”

Stults says the SEU has not faced any organized opposition, although she has encountered misperceptions about what it is and is not. Residents in favor of fully replacing DTE with a municipal electric utility say the SEU is a step in the right direction but fails to meet the urgency needed to address climate change. “[The SEU] will not be enough to reach the city’s 2030 renewable energy goals, or to address our chronically unreliable power grid,” Greg Woodring, president of Ann Arbor for Public Power, said in a statement.

Key to the long-term success of an SEU is that community members feel like they have a stake in its development, said Byrne, who worked on the Delaware SEU. “The problem is, if you're inside government, is it really the community that's governing, or is it really the bureaucracy, if you will?” he asked. He suggests that Ann Arbor “keep this entity close to communities.”

DTE Energy, the investor-owned utility that serves Ann Arbor, said in a statement to Smart Cities Dive that it is “dedicated to supporting the City of Ann Arbor's clean energy goals.” DTE likened the SEU to its MIGreenPower program, through which customers can pay to support clean energy. “When coupled with DTE's planned investments in clean energy, these voluntary, fee-based programs help accelerate economy-wide decarbonization while maintaining reliability and affordability,” DTE said.

A model for other cities?

Could Ann Arbor’s version of an SEU work in other U.S. cities? “From an engineering standpoint? From a social, economic standpoint? Absolutely,” Mathieu said. “From a legal and regulatory standpoint, I feel like it depends on the laws in that state or jurisdiction.” But, she adds, “we can do it in one city and learn a lot and then see if it makes sense in other places. I don't think we’ll have lost much by trying.”

One challenge is convincing the people who review federal funding applications that this is an idea worth betting on, Mathieu said. “When we get this reviewed by other engineers who haven't been brought along to thinking about it that way, they’re like ‘No, this is crazy,’” she said. “We could be moving a lot faster if we can get over this barrier of people thinking, ‘This is the way it's always been, [so] this is the way it always should be.’”

These existing “rules” for maintaining the power grid’s stability are entrenched in its traditional orientation around large central power plants, Byrne explained, but communities could reconsider those standards in favor of a new paradigm.

“If you want to have renewable energy go faster, don't build it on the same model that got you in the dilemma that you now have, which is fossil fuel and nuclear power plants that are centralized and big grids that are very costly infrastructure,” he said. “Try and work on alternative infrastructures.”