Editor’s note: Read our earlier story for additional coverage of Baltimore’s 10-year solid waste plan.

Baltimore City’s draft solid waste plan contains big plans for organics collection and separation. Now, a U.S. EPA grant could spur the momentum the city needs for change.

The grant, announced earlier this month, would provide Baltimore with $4 million toward a composting facility at the city’s existing Bowley’s Lane Drop-Off Center. The facility would be solar-powered and divert 12,000 tons of organic waste from landfills, according to a fact sheet from the EPA.

Sophia Hosain, zero waste manager for the Department of Public Works, said using solar power would help with the city’s goal of moving away from “combustion-based power,” a nod to efforts to reduce waste sent to WIN Waste Innovations’ mass-burn incineration facility in Baltimore. The city is also searching for long-term disposal options for waste as it projects its landfill will fill up by 2035.

Hosain celebrated the EPA’s grant while acknowledging that more work would be needed to transform organics management in the city.

“We see this funding opportunity as a great first step in the right direction, but it’s clear that we are going to need a lot more local composting capacity to support our organics diversion goals,” Hosain said.

In 2018, the city set a goal through its Baltimore Food Waste & Recovery Strategy to reduce residential food waste by 80% and ensure access to organic waste collection for all residents by 2040. Meanwhile, a Maryland law passed in 2021 required large food waste generators within 30 miles of an organics recycling facility to begin diverting organics from their waste streams.

But despite those goals, the authors of Maryland’s draft solid waste plan, due for approval later this year, note that there’s currently “no easy way for the City to identify the food-waste generators targeted by [the state] law.” Compounding the issue, the city has no centralized organics collections program, nor a major facility to handle such waste.

Marvin Hayes, who leads the Baltimore Compost Collective, has spent years working to address those challenges. Hayes’ organization composts at a small facility in the city and collects food waste from residents, but he often needs to truck excess waste to a secondary compost location in Prince George’s County because there isn’t a location in the city with enough capacity.

Hayes said he provided the city with feedback on its EPA grant application, and calls the award an “amazing opportunity” for the city. After years of advocacy, he thinks the facility could lead to greater opportunities and represents a step forward for a city struggling to move toward a circular waste system.

“To have Baltimore make this big step, even if it's just a mid-size facility, is overwhelming for me right now,” Hayes said. “I think that this is not a period, but this is a comma. We can go so much further.”

Diverting organics

The city has plenty of room for improvement when it comes to diverting food and yard waste — an estimated 3.5% of organics were diverted in 2021 despite making up 21% of the waste stream. The organics that were diverted were primarily collected by nonprofits, community composters and small haulers.

The lack of a centralized organics program has led to some nonprofits filling in the gaps. One such nonprofit, 4MyCity, has drawn attention for both its food rescue operations and its organics processing, and has received backing from waste-to-energy operator WIN Waste. Christopher Dipnarine, founder of the four-year-old nonprofit, said his organization today serves more than 4,000 residents that signed up for his food rescue service.

Dipnarine, who said he has supported the city in its grant applications in the past, is nevertheless skeptical of the city’s efforts to build out composting capacity. He noted that the draft plan is not the first time Baltimore has aimed high for its organics diversion policy.

“This is not their first go at this,” Dipnarine said, noting 4MyCity has expanded without the city’s support. “Who’s to say that they’re going to be successful at it?”

4MyCity has enrolled the families it serves via food rescue into a program wherein it collects their food waste and provides it either to on-farm composters or processes it with the nonprofit’s proprietary aerobic digestion technology. But 4MyCity’s organics processing efforts represent “about 30%” of the work the company does on a typical day, Dipnarine said.

“The premise really is to get food out to the community and stop food waste that way,” Dipnarine said.

To date, that mirrors the city’s own organics priorities. Beginning in 2016, Baltimore began a campaign to address food waste, culminating in a pair of documents published in 2018: first, the Office of Sustainability’s Baltimore Food Waste & Recovery Strategy and second, DPW’s Less Waste, Better Baltimore. While the former focused on food waste specifically, the latter encompassed more strategies to improve solid waste and recycling.

The earlier strategy set out a bold vision of organics recovery — in addition to aspiring to 80% reduction of food waste, the plan also set a goal of 50% reduction of commercial food waste, diverting more than 85,000 tons of organics annually. But the Less Waste, Better Baltimore plan, developed by consulting firm Geosyntec, noted that the city was somewhat limited in what it could do without outside help, and so far the city’s efforts have mostly revolved around boosting food recovery and educational outreach.

This year’s draft plan nevertheless sets a timeline for the rollout of a more ambitious, comprehensive network of city-supported organics collection capacity, with support for policies that would generate a demand for such infrastructure. Among other measures, the draft plan supports a ban on commercial organics disposal in the city as well as a blanket ban on landfilling organic materials.

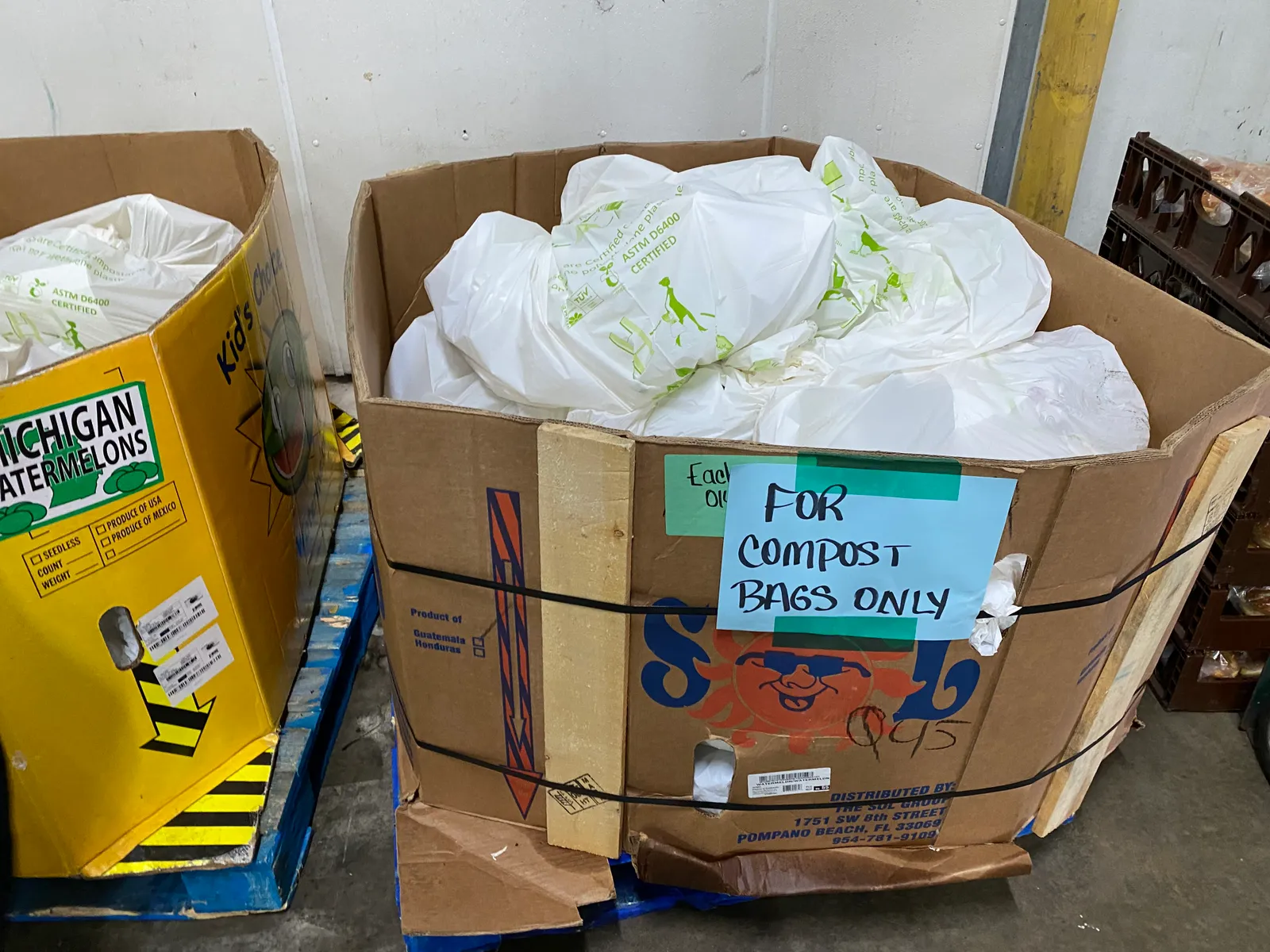

Currently, Baltimore operates five food scrap drop-off locations throughout the city, with plans to open five more this year, according to the draft plan. Between 2024 and 2028, the plan envisions piloting source-separated organics collection at public schools and government offices. Between 2029 and 2033, the city would then expand collections by establishing a three-bin pilot program to accept source-separated organics from residents, per the plan.

Hayes, who founded the Baltimore Compost Collective in 2017, said he diverts 1,500 pounds of organic waste weekly, collecting organics from residents directly and working in part with volunteer labor. He said he’s already nearing capacity, and with city support could see his operation expand further. If the city sticks to its goal of rolling out source-separated organics collection to all residents by 2033, he believes he could also play a bigger role in a circular ecosystem.

“If I had the city supporting this, we could do curbside compost, we could donate, reuse, reclaim some of those garbage trucks” and use them for organic material collection, Hayes said. ”That would be my goal: to be a hauler for those businesses that have to [divert] that organic material.”

Hayes isn’t just supportive of the city’s plans for more infrastructure, he also believes that education is essential to teach residents how to compost and why they would benefit. Hayes previously worked with the city’s Food Matters Program, which primarily offered educational training for the public and organizations looking to get involved in organics diversion, including support for a network of community composting sites. It launched in 2018 with the support of the Natural Resources Defense Council and Rockefeller Foundation.

Hayes continues to stay involved with educational training provided through the Department of Public Works at its GROW Center. He hopes the city will also consider sponsoring youth training programs in the future to help provide a pipeline of jobs and talents in a circular organics economy.

“Years back, we didn't think that we could stop people from smoking indoors. But what did we do? We ran campaigns,” Hayes said. “Composting hasn't been accessible to everybody. So we need to be able to educate them.”

Processing organics

Baltimore’s draft plan also lays out a vision for additional organics processing capacity for all the source-separated organics it anticipates collecting.

Such plans begin with a small-scale compost training facility with a capacity to process 3 tons per week. That facility is expected to open by 2028 and cost about $350,000 to build. The Bureau of Solid Waste envisions skilling up composting professionals at the facility, who could then support existing community composting efforts.

Over the course of the planning period, the bureau also expects to build at least one, and potentially more, covered aerated static pile composting facilities that can process 20,000 tons of feedstock annually at a cost of $3.5 million per facility. The plan expresses a preference for a public-private partnership to develop such facilities, with the city providing a land lease and partially guaranteed waste stream while a third party would build and operate the composting facility. The bureau estimates the first of those facilities could be operational in 2028.

Brenda Platt, co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, praised the plan’s decentralized and incremental approach to composting, contrasting it with cities like New York that are increasingly relying on codigestion at wastewater treatment plants or large-scale industrial facilities to process waste.

“Having some mid-scale, in-city sites that complement what the city is doing with the community composting and at schools and at urban farms and community gardens could work very well,” Platt said. “The city has a tremendous opportunity to help support a committed, community-driven process.”

Construction on the Bowley’s Lane composting facility likely won’t begin until 2025, the Baltimore Sun reported. Meanwhile, Baltimore has also applied for a Recycling Education & Outreach grant through the EPA to help fund its compost training facility. The city anticipates building such a facility at the Quarantine Road Landfill, which is slated for expansion, according to a spokesperson for the Department of Public Works.

Platt is supportive of building new compost facilities, but she believes the Baltimore plan’s greatest benefit could come from setting up infrastructure that will allow a network of community compost sites to thrive.

“The plan looks really strong on the front of bolstering local composting efforts,” Platt said. “We've been strong proponents, and we're very happy to partner with [DPW] on helping to advance composting in the city and [addressing] the unique challenges in Baltimore.”