Dive Brief:

- Micromobility companies Bird and Lime announced last week they're using augmented reality technology powered by Google in an effort to stop users from leaving their dockless e-scooters where they’re not supposed to be parked — a modern phenomenon known as “scooter litter.”

- The tools lets riders scan an area with their smartphone camera and, with the assistance of Google-provided data, then show them where they can park their scooter or prompts them to park elsewhere to comply with local regulations.

- Dockless, shared e-scooters have been touted as convenient and environmentally friendly transportation options, but the impact of scooter litter has ranged from annoying to dangerous and environmentally harmful.

Dive Insight:

Cities have been playing catch-up on shared e-scooter regulations ever since Bird became the first company to offer a dockless fleet in Santa Monica, California, in late 2017. Many companies, including Bird, launched without getting permission from the cities in which they began operating. Now, shared scooter providers and local governments are trying to find a balance that lets the companies continue to do business while also keeping streets safe.

In San Diego, one of the cities where Bird is testing its new AR technology, the city council is considering additional limits on the number of e-scooters it allows and on where they can operate and park. Chicago is requiring that e-scooters be able to detect when users ride on the sidewalk and that they have cable-locking technology, which allows riders to lock e-scooters up when they’re not being used.

New strategies for integrating shared micromobility into cities are to be expected, just as cities had to adapt to cars 100 years ago, a Bird spokesperson said.

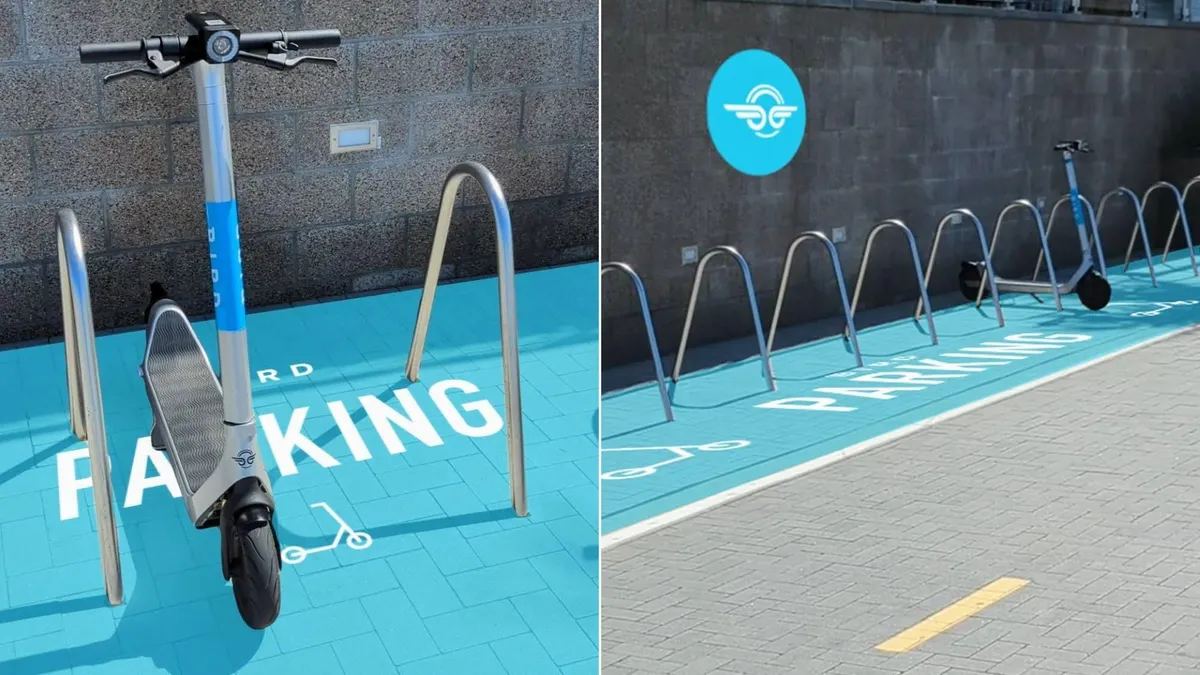

With the Bird Visual Parking System, once an e-scooter rider completes a journey, the Bird app will prompt the rider to scan the area with a smartphone camera. The app, using data provided by Google, will then indicate where the rider can park. Cities are asked to share information about designated e-scooter parking areas directly with Bird, which the company incorporates into its app. If the rider parks the e-scooter in an approved location, Bird will end the ride. Otherwise, the app will prompt the rider to park somewhere else. Lime's Visual Positioning Service operates in a similar fashion.

Bird is testing the technology in New York City, San Francisco and San Diego among “a sampling of riders,” a spokesperson said, and it plans to “roll it out across more cities in the near future.”

Lime is also testing Google's technology in San Diego plus five cities overseas. The company reported that riders who used the tool decreased “parking errors” by 26% compared with riders who did not use it.

Bird’s other efforts to prevent scooter litter have included educating riders on how to park their e-scooters, offering incentives for parking in a designated location or picking up fallen e-scooters, and allowing anyone in a community to report an issue with a vehicle improperly parked.

One concern often raised about scooter litter is the hazard it creates for sidewalk, bike lane, and road users, especially people who are elderly or have disabilities, who may have a more difficult time navigating around errant vehicles. Although national organizations do not track statistics related to pedestrian injuries from e-scooters, including scooter litter, emergency room doctors have given anecdotal reports about seeing injuries to pedestrians, such as broken bones and deep cuts requiring stitches, that were caused by e-scooters.

Some cities, including Seattle and Austin, have done some preliminary research of their own. A report this year from the Seattle Department of Transportation evaluating its e-scooter pilot program noted that, according to its weekly audits of parked e-scooters, in the fourth quarter of 2020, 21% of the vehicles “were obstructions.” That figure dropped to 8% by the third quarter of 2021. A 2019 study on injuries related to e-scooters done by government agency Austin Public Health reported that out of 192 incidents during a three-month period, only two “non-riders” were injured. However, the study noted that it “likely underestimates the prevalence of e-scooter related injuries.”

In 2019, advocacy group Disability Rights California filed a class-action lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California against the city of San Diego and shared e-scooter providers Bird and Lime and other parties for allegedly violating the Americans with Disabilities Act. As of press time, the lawsuit was ongoing against the city.

Asked whether Bird’s new technology could help crack down on scooter litter, Laura Saltzman, transportation policy analyst at Access Living, a disability rights advocacy group in Chicago, said that because the technology is new, it’s hard to say how effective it will be. She added that “ultimately, the companies themselves need to be made to worry about the consequences of scooter litter.”

Claire Stanley, a public policy analyst at the National Disability Rights Network in Washington, D.C., who herself is blind, said that scooter litter is “a big problem for people with disabilities” that “can literally become a physical barrier.”

Asked about Bird’s new technology, Stanley said that “in theory, it sounds like a great idea,” but that “of course, software and technology isn’t always foolproof, so only time will tell.” She also recommended educating riders on why scooter litter can be harmful.

“Education can only go so far, but I do think just more awareness is really important,” she said. “I don’t think people are malicious, I just don’t think people think about it.”