As inflation hit a 41-year high in March, much attention about its impacts has been focused on consumers, but the cities where those consumers live are also being affected.

Some cities are dealing with increasingly expensive construction projects or are considering delaying capital expenses, but certain observers say that the current environment isn’t prompting the idea of tax increases or layoffs to address higher costs.

Columbus, Ohio, for example, is feeling the pinch from supply-chain pressures and price increases, according to Chris Long, the city’s deputy director of the Department of Finance and Management. In 2021, the city spent $12.7 million from its general fund on supplies and $124.3 million on services, he said. Based on the 2022 first-quarter financial review, supply expenditures are forecasted to increase to $14.2 million, and service costs are projected to rise to $129.3 million.

But so far, Long said, the 2022 general fund operating budget is expected to absorb these increases without the need for additional revenue-increasing measures. He’s not aware of any projects that have been postponed or scaled back, and no discussions regarding increases in taxes or staff layoffs are currently underway. That’s not to suggest inflation isn’t having an impact. “The availability of goods and services, as well as associated price increases, continues to be a concern,” Long said, noting the city is still thoughtfully evaluating new hires along with travel and training expenditures.

Many other cities also appear to be proceeding cautiously in the current environment. “In many cities, the primary short-term reaction will likely be to order less and conserve — say, not replacing furniture this year, or postponing larger projects,” said Aly Spencer, partner at consulting firm McKinsey.

Language within Columbus’ standard-term contracts allows it to account for industry price increases, according to Long. This language, which it has used frequently in the past year, provides stability in the city’s vendor network and encourages more competition in bidding, as prospective contractors don’t bear all the risk of industrywide price increases, he noted. “Any difficulty in engaging vendors is largely due to supply-chain pressures and the resulting scarcity of products [and] not necessarily inflation and bidding,” he said.

In New York City, local officials are monitoring inflation and incorporating increased energy costs in their planning, according to a city spokesperson. The city is not considering layoffs or tax increases, although almost all local taxes city residents pay are controlled by the state, the spokesperson noted.

Overall, cities seem to be holding steady. “It’s not like the recession back in 2008, where many cities were having trouble balancing their budgets,” said Elizabeth Kellar, director of public policy with the International City/County Management Association. “This is a softer landing.”

The American Rescue Plan’s $130 billion in funding for local governments has in part helped to cushion that landing. Many cities have been using these funds to replenish lost revenue in the past few years, Kellar said.

But Columbus has prioritized investing ARPA funds in its communities, Long said. Most of its ARPA strategy has involved expenditures that are not capital-related, like partnerships with local nonprofits for community services, he added.

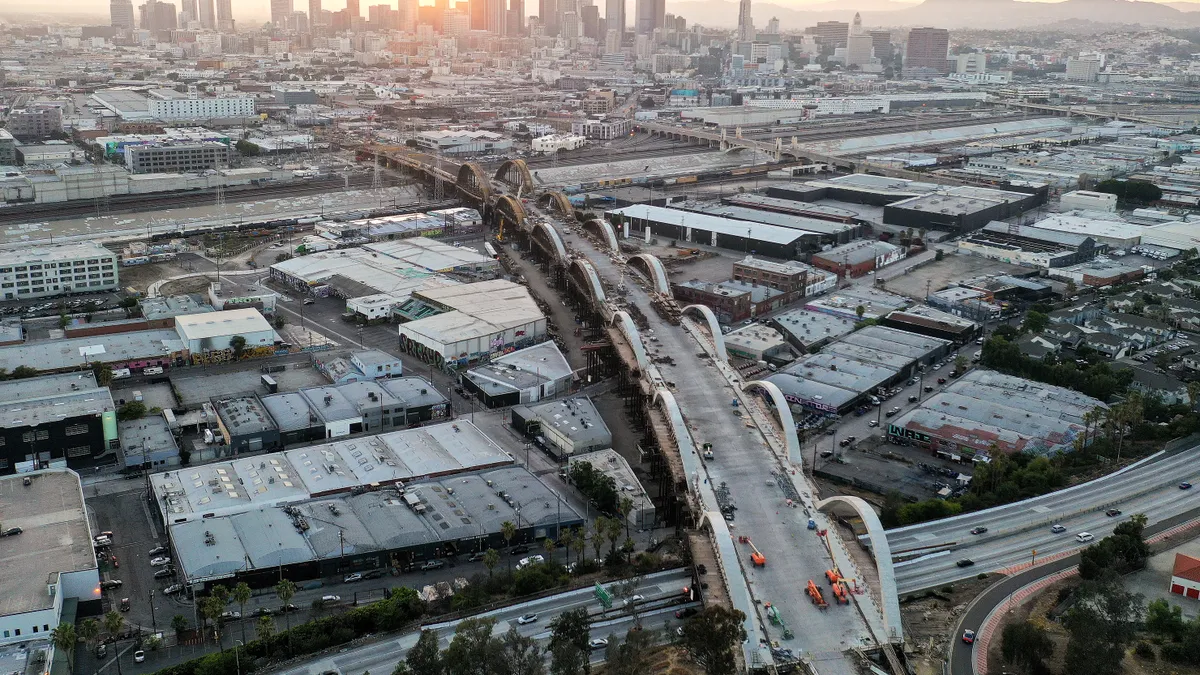

Impact on capital projects

City leaders say they are seeing price increases in construction projects. Prices for building materials jumped 20.4% between March 2021 and March 2022, the National Association of Home Builders reported.

Many local governments end their fiscal years on June 30 and complete their budgets between December and March for the following fiscal year, said Nick Grandy, construction and real estate senior analyst with consulting firm RSM. With inflation, a job for which a city might have budgeted $500,000 could now top $600,000, according to Grandy.

“These officials are now faced with the decision on how to proceed, whether that is drawing money from other sources, like the general fund, or delaying and even scrapping the project altogether,” Grandy said.

Delays in existing projects are making it more difficult for some smaller contractors to find the capacity to secure new projects, said Garo Hovnanian, a partner with McKinsey. “We’re seeing a decrease in bidders, and in some cases, there are not even enough to satisfy procurement requirements to award a project,” he said.

At the same time, some increased project costs are being offset by fewer projects moving through the pipeline, Hovnanian said. However, deferred projects might be at higher risk for inflation once they do start, he added.

Material shortages had already driven up costs, and New York City officials expect inflation to further exacerbate the problem. The city included inflation factors as part of the Ten-Year Capital Strategy it released in 2021, which it will update in January 2023, the spokesperson said.

The bipartisan infrastructure law may blunt the impact of inflation on some new capital projects, as it includes billions of dollars in competitive funding for cities, towns and municipalities. In addition, many large capital programs are funded by bonds, McKinsey’s Spencer said. “Where bonds have not been issued yet, they can be increased.”