"People live out loud and outside, and I do have concerns that public gathering, public music — that the surveillance is going to lead to more policing of public space."

Those are the words of Ursula Price, a racial justice and civil rights advocate in New Orleans who has opposed the city’s expanding connected camera network. She’s one of the many people featured in the second episode of City Surveillance Watch, which takes listeners on a coast-to-coast journey for a glimpse at how surveillance tech is used and how it affects real people.

We’ll dig into how private funding and public-private partnerships are enabling surveillance programs — from growing surveillance camera networks in New Orleans and Detroit that stream data to police monitoring centers, to privately-funded drones and license plate readers in Chula Vista, CA and Kansas City.

We’ll look into how law enforcement in Kansas City and Mt. Juliet, TN combine data from multiple forms of surveillance tech like license plate readers, connected cameras and video from Amazon Ring security cameras. We’ll explore why some urban residents are pushing to deploy more surveillance tech on their streets and in local businesses. And we’ll ponder a future in which privately-funded surveillance tech moves decision-making — once subject to government accountability and oversight — deeper into the shadows.

Listen and read along below, and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher or wherever you listen to podcasts.

TRANSCRIPT:

Sources featured in this episode by order of appearance:

- Ursula Price, executive director of the New Orleans Worker Center for Racial Justice, former director of New Orleans Independent Police Monitor

- Ross Bourgeois, New Orleans Real Time Crime Center administrator

- Renard Bridgewater, hip hop artist & community engagement coordinator for the Music and Culture Coalition of New Orleans

- Rayshaun "Raysh" Phillips, member and former fundraising chair, Black Youth Project 100 in Detroit

- Jeff Petry, director of administration for the Planning and Development Department, City of Eugene, OR

- Wendy Hood, parking enforcement officer, City of Eugene, OR

- Sgt. Jacob Becchina, Kansas City, MO Police Department

- John McKinney, president, Pebble Point Homeowners Association in Lebanon, TN

- Jameson Spivack, policy associate, Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown Law

- Tyler Chandler, captain, Mt. Juliet, TN Police Department

- Lee Tien, legislative director, Electronic Frontier Foundation

URSULA PRICE

Like, I live in a neighborhood called Gentilly. It’s kind of a bedroom neighborhood inside the city, and we have a large population of older people. And there’s not a lot of, like, violent crime in Gentilly, but there is a lot of petty crime, a lot of property crime. And it makes the older people feel very unsafe, and if you go to the Gentilly neighborhood associations, you’re going to hear people applauding surveillance as something that makes them feel safer. And I honestly question the efficacy of surveillance for reducing crime or keeping people safe.

KATE KAYE

Listeners met Ursula Price briefly in our first episode. When I spoke with her virtually in October, she was outside in her backyard, tending to some herbs growing in her garden – and getting a little space away from the kids.

PRICE

We’re doing home school, so this is my office. [laughs]

KAYE

For years, Price has actively opposed a growing surveillance camera network in her city of New Orleans. The city began installing the cameras in 2017 as part of a broader $40 million citywide public-safety plan.

The original plan called for security cameras in 20 crime hotspots. Now, the network has expanded to include around 800 cameras. About half of these are government-owned cameras installed in all city council and police districts, while the other half are privately-owned cameras, some of which are involved in a related video surveillance program.

These are not a bunch of standalone cameras though. Like most smart and safe city tech, they're always on and connected. This growing network of cameras are linked into the New Orleans Real Time Crime Center — where at any time, day or night, staff can access video imagery from them to investigate a crime or even keep an eye on a fire or a flood.

New Orleans, of course, is not alone among U.S. cities that are actively expanding networks of surveillance cameras, many of which connect into these same sorts of monitoring centers where law enforcement or other staff can not only view real-time camera imagery, but tap into analysis of information feeds through sophisticated software.

My name is Kate Kaye. In our first episode of City Surveillance Watch, I spoke with city staff and policymakers, civil liberties advocates and law enforcement about the issues surrounding the expanding use of surveillance technology in urban places and beyond. We discussed the forces influencing cities to procure these technologies; how surveillance tech is defined; and the risks and unintended consequences of surveillance tech use.

In today’s episode, I’m digging deeper into how surveillance tech is used right now across the country — from New Orleans to Detroit, to a little lakeside homeowner’s association neighborhood in Tennessee, to a college town in Oregon.

I’ll talk to people affected by these technologies every day, on the ground. Some fighting them, some celebrating them. These are stories that highlight some important trends and tease out those grey areas that lie between smart and efficient tech use, and ubiquitous surveillance.

[Sound - Intro theme]

KAYE

Ursula Price says there wasn’t much engagement with community members before January 2017, when the city of New Orleans launched its connected cameras and Real Time Crime Center program.

Despite the fact that at the time Price ran the city’s police oversight group, the New Orleans Independent Police Monitor, she didn’t catch wind of the plan until late 2016 when the plan was made public.

PRICE

Honestly, it was a red flag that no one told us this was happening, and because we haven’t had a ton of transparency, we don’t – I don’t have confidence about how broad this system is.

Frankly, the cameras – we know about them because they are visible, because we see them, but there was not a great effort to alert people to the fact that these were coming.

KAYE

It’s important to note, The New Orleans Police Department was investigated by the U.S. Department of Justice in 2010 and 2011 for an alleged pattern of civil rights violations. That led the DOJ to enter into a consent decree with the city of New Orleans and the police department aimed at establishing effective, constitutional and professional law enforcement.

So, there was already a history of concern regarding civil rights violations by police against residents in the city before the surveillance cameras and crime center came about. The lack of transparency regarding the public safety plan, it only fueled long held distrust between the police and some city residents, says Price.

PRICE

The lack of transparency can breed a whole lot of distrust. If the city would just, be a little bit more upfront about what they were doing, some of these concerns could be alleviated.

So we already have a police department that has been shown to violate people’s civil rights and to disproportionately violate the rights of Black and brown people. They have used their history of policing as the justification for where these cameras should be placed. So, what that means to us is, those who are over-policed in the past will be over-policed forever because every decision today is being made on the basis of the discriminatory policing that happened yesterday.

KAYE

Price is no longer with the independent Police Monitor. Today she serves as executive director of the New Orleans Worker Center for Racial Justice, where much of her work revolves around protecting the rights of immigrant workers.

She says there is a lot of fear among immigrants in the city about the use of cameras and license plate readers to facilitate arrests by U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement.

But some people in the city, they want more cameras, says Ross Bourgeois. He’s the administrator of New Orleans’s Real Time Crime Center.

BOURGEOIS

They want to prevent vehicle burglaries, they want to prevent folks from hanging out outside of a problematic alcoholic beverage outlet or outside of a problematic gas station. We’re seeing and we’re hearing from people on the ground when we’re installing cameras in these neighborhoods, people come out of their houses and thank our staff. They thank our staff for the ability to let their kids play in their yards, you know, in the evenings and they ask our staff or thank our staff for putting the cameras up because that’s going to drive that element out.

KAYE

Bourgeois has been in charge of the Real Time Crime Center since its inception. The center costs $2.5 million to operate annually.

These real time crime centers have sprouted up across the country. A November report from Electronic Frontier Foundation says there are 80 of these crime centers in the U.S. in 29 states, with the largest number concentrated in New York and Florida. Think of them as localized versions of those Fusion Centers operated under the U.S. Department of Homeland Security; I mentioned those in the first episode.

Bourgeois calls the cameras strewn throughout New Orleans and connected into its Real Time Crime Center a “force multiplier.” He says they save hours of time police investigators would have to spend to track down information that now can be obtained readily via historical video surveillance data.

Because they’re connected, the cameras allow video data to feed into the crime center constantly. And as with all sorts of smart city tech, digital software is what makes the massive volume of video data flooding in from these cameras searchable, interpretable and, well, useable.

But Bourgeois and the other crime center staff, they're not sitting there with their eyes peeled, watching every single camera at every moment. Instead, to view and analyze footage from particular cameras when they need to, they use video management software from Genetec, paired with video intelligence management software from Motorola, called Command Central Aware.

BOURGEOIS

So we have a software platform that allows us to monitor the cameras in the areas where incidents are taking place. So our software platform is connected directly to the 911 center and anytime an incident for police, fire or EMS is generated in the computer-aided dispatch system, if there is a camera within a pre-determined geographic radius of that incident, we get an alert and the cameras spin up automatically, so our staff at the crime center doesn’t have to know where the cameras are located.

KAYE

The Real Time Crime Center follows a data use and access policy that states video can only be archived upon request from a public safety agency – for instance, if police ask for video from a camera in the area of a car accident or homicide, or if public works wants video footage to assess street flooding.

The Real Time Crime Center is not part of the New Orleans Police Department. It operates under the city’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness. Despite the similar name, there’s no affiliation with U.S. Homeland Security.

So, unlike other real time crime centers elsewhere operated by law enforcement, Bourgeois and the rest of the crime center staff in New Orleans, they’re not on the police force. They’re civilians, he says.

And don’t forget – about half of the cameras tied into this network are privately owned, by local businesses and property owners who pay to get their cameras connected into the Real Time Crime Center through a related city effort called Safecam.

That Safecam program, launched in 2018, is a joint initiative of the City of New Orleans and the nonprofit New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation.

It’s one of the many public-private partnerships involving surveillance tech use that you’ll hear about today.

So, this Safecam program in New Orleans: Participating businesses must cover their own equipment costs. They spend an estimated $250 to buy each connectable camera, another estimated $150 to install each camera and around $18 per month for cloud storage of video data.

BOURGEOIS

So if there is an incident that takes place near one of those private-sector cameras, that private-sector camera will spin up no different than a city-owned camera and our staff can utilize those private-sector cameras in the same manner in which they would utilize a city-owned camera.

KAYE

So, the fact that around half of the cameras linked up to the Real Time Crime Center in New Orleans are privately owned, and the fact that the program is not run by the city’s police department, Price says those things matter because they have a direct impact on transparency and accountability of the program.

Here’s Price.

PRICE

And of course New Orleans Police Department tries to maintain, well, it’s not our technology. We’re not responsible for it, we just use it. So this partnership also confuses responsibility, public records and sunshine law because they have sort of created a secondary entity around the surveillance system that doesn’t leave the public safety system accountable.

KAYE

Notably, more than half of the original funding for the public safety program that spawned the New Orleans Real Time Crime Center and camera network – it came from the city’s Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, which is state-owned.

You may have heard, tourism is kind of a big deal in New Orleans. I mean, there may be no other destination in the U.S. quite as steeped in or synonymous with one-of-a-kind vibrant culture and free-spiritedness as New Orleans. The street music and the performancel; the unique stew of history, spiritual practices and foodways; and the just-plain playful, eccentric character of the place.

Price and others who oppose the proliferation of connected cameras throughout New Orleans, they argue they have a stifling effect on the very things that draw a lot of those tourism dollars.

PRICE

First of all, New Orleans is a very street culture – something I love about New Orleans. People live out loud and outside. And I do have concerns that public gathering, public music - that the surveillance is going to lead to more policing of public space.

[SOUND: “Huckabucks for Breakfast” by Slangston Hughes]

KAYE

New Orleans native Renard Bridgewater is a hip hop band leader and emcee – he goes by the name Slangston Hughes. This is one of his tracks.

Bridgewater is also community engagement coordinator for the Music and Culture Coalition of New Orleans. And he’s trained as a community police mediator through the New Orleans Independent Police Monitor – the law enforcement oversight group Price used to run.

Bridgewater says cameras in the city are ripe for abuse and alter everyday ways of life for people there. Here’s Bridgewater.

BRIDGEWATER

It’s one of those things where I’ve actively seen as a police officer’s approaching a street performer, like, they’re automatically packing up their instruments, they’re turning the amp [off] and they’re getting the hell outta there. You know, so I can only imagine, if that’s happening where someone is tangibly there in a uniform, if they’re seeing a camera up there, you know, aware of a camera that’s visible, you know, how that’s going to deter that cultural activity, right? Like how that’s going to deter that individual from setting up in that pitch – is what they call it, that pitch – on Bourbon Street or on Royal Street or somewhere in the French Quarter because they don’t feel safe, they feel like they’re being watched, right, they feel like they could potentially be targeted.

Surveillance technology or camera is an extension of the law enforcement that they’re already unfortunately familiar with and have been harassed by or threatened with arrest, etcetera.

Sound: chanting from October Eye on Surveillance rally

KAYE

Bridgewater joined a rally in October led by an organized New Orleans-based anti-surveillance group, the Eye on Surveillance coalition. They marched from the Real Time Crime Center to city hall.

They wanted to raise awareness in support of an ordinance that would ban the use of surveillance tech including facial recognition and other biometric software, stingray cellphone trackers and predictive policing software.

Local officials and residents were surprised in November when reports emerged about the New Orleans Police Department using facial recognition following years of assertions that they did not use face recognition. It turned out the agency has access to the technology through its state and federal partners.

The work of surveillance opponents like Eye on Surveillance has begun to pay off. After months of delaying a vote, the New Orleans City Council passed the ordinance 6-1 on December 18th, prohibiting use of facial recognition and those other surveillance technologies by the police department by the new year. The ordinance does not, however, affect the camera programs or the Real Time Crime Center.

[Sound: “Champion Song” by Slangston Hughes]

Bridgewater argues some of the money that goes toward surveillance tech and other policing in New Orleans could be diverted toward programs that foster stronger communities.

BRIDGEWATER

So, I always kind of have those conversations with folks, the discussions with folks, even if they are in opposition to what we’re proposing. Especially a lot of elderly Black people certainly want those cameras, and I understand why.

I always try to propose to folks in opposition, it’s like, what would that look like if even a fraction of that amount of money was going towards mental health services, after-school youth programming, healthcare, a living wage for musicians, culture-bearers and any folks that’s in this city, right?

But we’ve continuously been doing the same cyclical thing over and over again of continuously investing in policing, investing in surveillance technology, believing that that’s keeping us safe and deterring criminal activity but that’s not really the case.

SOUND: Black Youth Project 100 protest against Project Greenlight in 2019

KAYE

Let’s make a pitstop in Detroit. There’s an expanding public-private surveillance camera program happening there, too.

[SOUND: More BYP 100 Project Greenlight Protest]

That’s the sound of activists from the group Black Youth Project 100.

In 2019, members and supporters descended on a busy Detroit coffeeshop. They carried signs and chanted, and encouraged people waiting in line for their lattes to call their city officials to urge them to dismantle Project Green Light, Detroit’s public-private surveillance camera network program.

Project Green Light launched in 2016 at eight Detroit gas stations. The city found that in the first half of 2015, approximately 25% of violent crimes in Detroit reported overnight took place within 500 feet of a gas station. So, they created Project Green Light in the hopes of improving neighborhood safety and growing local business.

The program has grown exponentially. As of January 1, 733 Detroit locations have installed Project Green Light cameras, a Detroit Police spokesperson tells City Surveillance Watch. These cameras are installed inside and outside liquor stores, gas stations, and restaurants – and, even apartment buildings, motels, healthcare facilities and places of worship.

To participate, businesses own and operate connected surveillance cameras that stream video footage into Detroit’s Real Time Crime Center. Detroit has allocated at least $12 million since 2019 to that crime center, according to the Detroit Free Press.

Oh, and yes, there are literal flashing green lights stationed outside participating businesses that the businesses themselves have to pay for — along with signs, cameras, and connectivity services. But the ‘Green Light’ name, it has another connotation: speedier police response.

In exchange for partnering with the police program, calls for service at participating business locations are categorized as "priority 1", sometimes resulting in quicker response time to 911 calls. Many – including some local businesses and the American Civil Liberties Union – argue the program amounts to a private partnership form of public safety pay-to-play.

Lifelong Detroiter Raysh Phillips — a former fundraising chair for Black Youth Project 100 or BYP 100, that group that protested at the coffeeshop — says the cameras are invasive and seem ever present.

PHILLIPS

Yeah, they’re very invasive. You see them all along – at, literally almost every major business and it really just feels like you have eyes on you at all, like 24-7. No matter what you do, someone’s watching you.

KAYE

Phillips also worries that the city is profiling people captured through Green Light cameras. In fact, there’s plenty of concern that Detroit could use its facial recognition software in conjunction with Green Light camera footage to identify people in real-time.

The Detroit Police Department does use face recognition software from DataWorks Plus, a technology used in conjunction with still photos from Project Green Light cameras. NBC News reported in 2019 that Detroit Police used face recognition in a homicide case to identify a still image of a suspect picked up from a Green Light camera.

But Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan in 2019 said on Twitter that Detroit PD would not use facial recognition software in real-time with live stream video.

Regardless, there has been high-profile media coverage of wrongful arrests resulting from Detroit PD’s use of the DataWorks Plus technology. After using the facial recognition, Detroit police misidentified suspects which led to false arrests of two Black men in 2019 and 2020.

Still, despite vocal opposition within the city and among civil liberties activists around the country, Detroit in September extended its facial recognition software contract with DataWorks Plus, agreeing to pay an additional $220,000 on top of the $1 million the city agreed to pay the company in 2017.

Detroit’s Project Green Light website refers to the program as a public-private-community effort centered on developing real-time surveillance connections between the Detroit Police Department and local businesses.

So, think about that — rather than calling it something like, I dunno, Detroit Surveillance, the program has a brand name: Project Green Light.

Other police departments use brand names for their surveillance efforts, too. Remember how the Mt. Juliet Police Department calls its license plate reader system, “Guardian Shield”?

As any good political analyst will tell you, perception is tied directly to language. Words matter. It’s one reason Ross Bourgeois in the New Orleans Real Time Crime Center does not like calling that city’s connected video cameras “surveillance cameras.”

BOURGEOIS

Well, I believe that the term ‘surveillance’ has a negative connotation.

KAYE

Instead, Bourgeois says he likes to call them "security and public safety cameras." But he says it’s not just about perception; he says it’s based on how the cameras are actually used.

BOURGEOIS

The technology transcends all of the disciplines of public safety and they’re not strictly crime cameras even though that’s the colloquial term for the devices that are actually mounted on the poles.

KAYE

Bourgeois says city agencies might use video footage to analyze the causes of fires or hazmat incidents. Or, public works can use video to compare visible water on a street to data from a pumping station to evaluate significant flooding.

So, this is another example of how cities are finding additional ways to use tech and data originally intended for law enforcement purposes.

Think of Rekor – that license plate reader and vehicle recognition software firm we met in the first episode – and how that company hopes to sell tech its law enforcement clients use to other government agencies.

Or how the City of Eugene, OR uses license plate reader tech – often thought of in the context of law enforcement – for purposes that have nothing to do with crime or public safety.

To Jeff Petry, the director of administration in Eugene’s planning and development department, license plate readers are a parking and mobility industry thing.

JEFF PETRY

I’m not in law enforcement, it’s not an industry that I track. What I do track is the parking and mobility industry. And so, for me, I view an LPR system more on the transportation system, and then within the parking industry, it’s a common practice to try to get away from either chalking tires, or the other part is other cities enter every license plate they see on the street and so those are two very laborious processes and we like to have smarter processes for us.

KAYE

Eugene has used license plate readers to manage parking enforcement since 2010, but the city has expanded their use for its University of Oregon campus and downtown districts. Today, LPRs made by Vigilant Solutions are installed on a small fleet of electric cars like the one driven by Wendy Hood, that Eugene parking officer we met last time.

Data from those license plate readers flows into a mobile app system the city introduced in 2020.

Petry says it’s all about giving residents the convenience of digital tech they expect – even in their interactions with city government.

PETRY

And so we started looking at some of the complaints our customers were giving us and one of the biggest complaints was buying a parking permit.

So the traditional, paper, monthly hangtag permit involves a mailing process, stuffing envelopes, forms to fill out, online systems, and both our downtown commuters and our residential parking customers really just wanted to do it on their phone. And so, I think the world has changed in many ways, but one of the things is trying to move technology that’s commonly used by a lot of people into the parking world.

And so, just thinking about our city's policies and our goals and trying to be efficient and safety and meet our customer expectations, we switched to a digital permit system which allows our customers to register their permit and license plates which they had been doing traditionally.

And so the cameras on the LPR do capture the license plates and they sync back to our permit management database or our payment system. Using a phone app, you can also pay in maybe downtown locations with the phone app, so it just syncs back to the camera and the officers can just drive their bright green Chevy Bolt electric vehicles and it would notify them if there’s a violation – or they just keep driving.

[SOUND from the City of Eugene’s parking enforcement LPR system]

KAYE

When I visited Eugene in October, parking officer Wendy Hood showed me how the LPR system works when enforcing a two-hour free parking zone on a street downtown. But first, we'll take a quick break.

[AD: Sign up for Smart Cities Dive's daily newsletter, here]

HOOD

On a normal day in a two-hour zone we would start scanning. We’d go around and do whatever it is that we have to do for the day and we’d come back approximately two hours later and re-scan that section. And any vehicle that hasn’t moved, it will alert us.

KAYE

When Hood started in parking around six years ago, the primary tool of her trade was not high-tech cameras. It was chalk.

HOOD

So with the chalking we’d be in our little scooters, we’d have our chalk stick and we’d drive really slowly next to the vehicles and we would chalk their tires ... and we would log the time that we entered the block in our log books.

KAYE

Then she’d come back two hours later and pick up her marks from the earlier time. That’s how she’d know who had been parked longer than the free two-hour window, and therefore which vehicles should get ticketed.

So, yeah, obviously this is like night and day in terms of convenience and efficiency. But some people don’t necessarily believe these high tech contraptions are just being used for parking enforcement, says Hood.

HOOD

There are some people out there that think our cameras are set up to, for facial recognition and to kind of keep tabs on people, and that is absolutely not what they’re made to do.

You know with anything, there’s people out there that definitely get upset and they don’t believe you no matter what you tell them. You know, because we’re government, we’re city government and a lot of people have that in their head that we’re being dishonest, we’re not telling the full truth, we’re not really just out doing parking. It’s a hard one.

KAYE

The cameras used to scan plates in Eugene don’t enable facial recognition — though Vigilant Solutions, which makes those cameras, does also make facial recognition software that clients could use in conjunction with LPRs.

But let’s be clear — this license plate reader system, it isn’t just a digitized replacement for chalking tires. Like all the technologies we’ve been talking about, it is capturing data that did not exist before: plate numbers, precise locations, dates and times a vehicle was parked, and photos of the parked vehicle captured with the LPR cameras.

All that data capture means it has surveillance implications.

Think of this scenario: In the past, if somebody parked for half an hour to go pick up a sandwich or, like, buy a couple pre-rolls at the cannabis shop — this is Oregon, folks – he wouldn’t have had his license plate number recorded anywhere. Now, it’s in the system’s database for 30 days until it’s purged.

And if there’s a citation issued, the city’s policy requires that the data be stored in the city’s database until the case is adjudicated.

Petry says the city’s contract with Vigilant Solutions does not allow the company to do anything with the data captured by the system.

Eugene’s policy does, however, allow for law enforcement to access the data for official law enforcement purposes if specific criteria are met. He says law enforcement has never made such a data request.

PETRY

We have a process where it’s much like a public records request, there’s a process that law enforcement would need to follow to get permission and logged and filed and we haven’t had those requests.

And I do think about data privacy and the rights of our community and that’s a priority for us and it’s probably the greatest asset that we hold in trust with our community, and that’s true for any data system that any public agency uses.

So, when we went into this process it wasn’t a willy-nilly business decision. We are public servants and we have another layer of, levels of attainment that we have to meet. And so by going through the system and making it very clear in the contract what happens to the data, that the data gets deleted so there’s only 30 days’ worth of information in our system, that any access to the data requires written permission from the city and the intended use – even for algorithms to kind of, quality control.

So it’s our data and we control it and I think that we put measures in place to make sure that the information is not shareable from our side. We do not connect it to Department of Motor Vehicle information, we don’t know who owns that vehicle, we don’t know anything about that vehicle. And so we just have to be thoughtful and considerate and vigilant about how we use our community’s data.

KAYE

OK – so cameras and license plate readers can have uses that have nothing to do with crime or law enforcement. But cities and private entities typically aren’t buying LPRs or connected cameras, paying for data storage or investing in war room-like monitoring centers just to assess flooding or ease traffic congestion. They’re doing it to reduce and solve crimes.

All right. Now, we’re going to Kansas City.

JACOB BECCHINA

Technology 100% contributed to solving this crime and getting this suspect in custody in less than a day.

KAYE

That’s Sergeant Jacob Becchina of the Kansas City Missouri Police Department.

He’s talking there about how the police department combined data from video surveillance cameras and license plate readers to help find the suspect in the murder of 71-year-old Barbara Harper. She was shot in 2019 while driving home from work one night. Police say, despite the fact there was little information to go by, they found the suspect in a matter of hours.

BECCHINA

She was on her way home from her night shift at the postal service and was just, literally just driving down the highway. The suspect pulled alongside of her and fired one or more shots into her vehicle striking her, and she was deceased there at the scene.

KAYE

There’s even a video featuring KCPD detectives discussing how surveillance camera footage was used in conjunction with data from the city’s license plate readers to identify the murder suspect. Here’s a clip from that video.

[Sound: Clip from KCPD video about the Barbara Harper investigation]

The suspect was arrested and charged with murder, unlawful use of a weapon and unlawful possession of a firearm.

The KCPD has used license plate readers since 2010, installing them in locations throughout the city and on police vehicles. Like other law enforcement agencies, they publicize when tech investments pay off by helping to solve crime – like with that video.

And it’s worth noting that video touting the police department’s tech use was produced for the Police Foundation of Kansas City — a nonprofit that helps the Kansas City Missouri Police Department purchase technology.

The foundation has provided drones to KCPD, along with other tech like video analytics software and license plate readers. The foundation’s website lists sponsors including local bank and real estate firms and other charities.

Police foundations across the country help law enforcement pay for a variety of surveillance tech including drones, which are becoming common tools for aerial surveillance. Take Chula Vista, CA: The police department there in 2019 praised the Chula Vista Police Foundation for purchasing two new drones to add to its collection. The department’s website says they use drones as first responders to document crime and accident scenes, search for missing or wanted persons, or to evaluate fires or damage after major incidents or natural disasters.

But it’s worth checking out where the Chula Vista Police Foundation’s money comes from. The foundation’s sponsors page lists a handful of local real estate companies, local dental and medical healthcare providers — that sort of thing.

But you’ll also find some of the biggest names in surveillance tech.

Motorola is listed in the foundation’s Lieutenant’s Circle. Companies including Axon – which makes tasers, cameras and drones, and Verizon – which provides video surveillance technologies and 5G connectivity services – they’re in the Chula Vista Police Foundation’s Captain’s Circle of sponsors.

You might think of this as another way for surveillance tech firms to promote their products in the law enforcement industry, and even help buy their products. These companies support police foundations across the U.S. According to the investigative nonprofit, Little Sis, Amazon, Microsoft and Motorola partner and donate to the Seattle Police Foundation. Motorola also donates to police foundations in Washington, DC, Chicago and Detroit. Verizon has supported foundations in Chicago and New York.

So, yeah — private dollars are seeding surveillance tech all over the country.

Let’s head to San Francisco, where there’s another growing privately-funded camera network. This one is supported through funding from a tech entrepreneur named Chris Larsen. He’s spent millions of dollars to buy high-definition cameras stationed throughout the city, along with the equipment used to monitor those cameras.

And there’s no affiliation with local law enforcement in this case. Larsen told the New York Times in July that the “winning formula” for trust between the community and law enforcement is complete community-wide camera coverage controlled by citizens.

But the public safety surveillance tech trend lies in public-private partnerships. And companies like Motorola – which supplies tech for that San Francisco project and for the Real Time Crime Center in New Orleans – they see opportunity in that public-private trend.

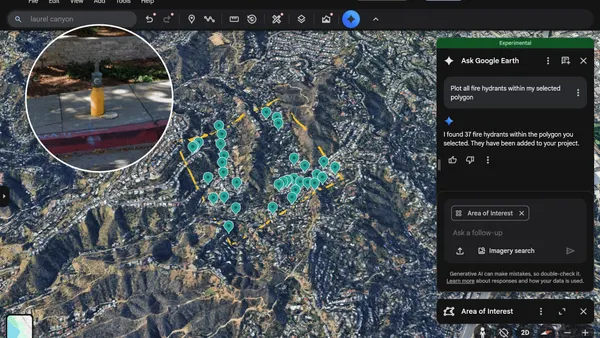

Motorola in July introduced a video security and analytics technology suite designed specifically for public-private partnership programs. It includes new license plate recognition camera tech that can link up into police monitoring centers through the cloud.

The company did not respond to multiple requests to comment for the City Surveillance Watch podcast.

Motorola could be making a smart bet. Whether we’re talking about programs funded by police foundations that benefit corporate interests, or funded by local businesses picking up the tech tab, we could see more privately-funded anti-crime tech interventions like Project Green Light in Detroit, Safecam in New Orleans, or rogue efforts like what’s happening in San Francisco.

Think about it: city coffers have run dry amid the pandemic. Meanwhile, residents are pushing for cities to defund the police. It’s worth pondering whether these forces will inspire more public-private partnerships or privately funded tech to fill in the gaps where there’s no longer government funding or resources.

If that happens, some argue these private approaches will push tech decision-making that was once subject to government accountability and oversight further into the shadows.

…where they are not always subject to legislation or policy crafted by and voted on by elected officials.

…where they aren’t always subject to technology impact reviews or community comment periods.

...and where they are not always subject to standard government oversight, transparency and accountability.

Here’s Jameson Spivak, policy associate at the Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown Law.

SPIVAK

So the fact of the matter is a lot of law enforcement surveillance technology, as I mentioned, is adopted without approval or knowledge by elected officials or by the public, so it’s not necessarily the city weighing the pros and cons. In this case it’s law enforcement themselves because they’re doing it without transparency.

KAYE

Privately-funded surveillance tech — it isn’t just happening in stores and street corners in big cities, though. It’s happening everywhere, even in small, lakeside neighborhoods.

Let’s head to Tennessee.

JOHN MCKINNEY

Yeah, our neighborhood is actually a pretty old subdivision. It was around ever since segregation actually, and we’re on the banks on the shore of Old Hickory Lake. But it’s a – we have direct access to the water from our neighborhood. We have about 38 houses right now and a lot of those are summer homes, lake homes that people don’t typically live in year ‘round.

KAYE

John McKinney is president of the Pebble Point Homeowners Association. It’s near Lebanon, TN. That’s outside Nashville.

MCKINNEY

When I was elected president, I kind of told everybody and made a promise that one of my main goals was safety and security in the neighborhood.

KAYE

Even in a little, off-the-beaten-path place like Pebble Point, residents experience crime, says McKinney.

MCKINNEY

There was a few incidents of trash dumping – illegal trash dumping in our neighborhood. You know, there was some non-residents kind of loitering I guess, in our neighborhood, on our private roads. And none of that really came to – you know, it wasn’t really a big deal at that time. But we had an incident that happened last year to where somebody’s car was broken into and that led to gunshots being fired and a high-speed getaway by the suspects.

You know, luckily nobody was hurt. You know, there was no suspect information. Nobody had any information other than Ring cameras that were on the house, and you couldn’t get a tag number and you couldn’t get any description of the vehicle because they were going so fast. And there was no suspect identified or apprehended.

That’s kind of what prompted us to call an emergency HOA meeting and kind of put our heads together and try to figure out what we could do, if anything.

KAYE

A few months later, Pebble Point had a license plate reader camera installed at the entrance of the property, which also serves as its only exit. The HOA pays around $1,900 a year for the service. They signed a five-year contract.

The dispatch center in the local sheriff’s department of Wilson County has access to data from that license plate reader, and HOA members can tap into it – but only if there’s a police report related to the incident.

It turns out Pebble Point’s license plate reader system comes from the same firm supplying similar technology to the nearby Mt. Juliet Police Department: Rekor AI.

MCKINNEY

But I always follow local police departments in our area pretty closely because I grew up in the Mt. Juliet area. And when they picked up that system, they were catching stolen vehicles and wanted vehicles every day.

KAYE

So, yeah, remember how the Mt. Juliet PD, they send out social media posts when their license plate reader system helps them track down stolen vehicles? All that promotion inspired McKinney and his privately-run HOA to try out the same technology.

Tyler Chandler – the Mt. Juliet, TN Police Department Captain we heard from in episode one – he says he’s spoken to other local homeowners’ associations and neighborhood organizations that want their own LPRs. Here’s Chandler.

TYLER CHANDLER

Neighborhoods are pushing it more than we are, which is very surprising, but again, our community sees the benefits of this technology, and they want to see it deployed more, I guess, micro to their neighborhoods.

KAYE

Of course, a lot of residents in these communities, they already have some form of home security tech. And one popular set of home security products in particular is creating what some call a public-private surveillance network effect: Amazon Ring.

McKinney mentioned how Amazon Ring connected home security cameras’ picked-up footage of the alleged suspect in the car break-in attempt in Pebble Point. He says he personally owns four Ring cameras.

MCKINNEY

Whenever I go on vacation, I like to be able to monitor, see who’s delivering packages in my yard, maybe get the neighbor to go pick up a package if it’s going to rain. And just peace-of-mind to know that, what’s going on at your house when you’re not there.

KAYE

Ring camera owners are encouraged to use Amazon’s Neighbors mobile app to upload video of suspicious incidents from their cameras and check out video posted by other people in their vicinity.

The app even intersperses Ring camera user videos with police department alerts that are fed into the app. Think of it as something like a Facebook feed focused exclusively on hyper-local alleged neighborhood crime.

And because it sends video data up into the cloud, Ring is more far-reaching than your traditional home security monitoring system.

Ring camera owners may not realize they are actually facilitating a widespread connected surveillance camera network, suggests Lee Tien. He’s the legislative director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation we heard from in episode one. He says Ring is much more than a collection of separate cameras installed at separate homes.

LEE TIEN

People might not be aware of what the capacity of the device they’re using is. They might not think about the difference between I have a camera and, gee, now everybody on the street has a camera. You know, there is a difference in kind between the thought that, oh yes, I’m able to see my porch, and oh, wait a minute, when everybody on my street has one, it’s not possible for any person to walk, like, from point A to point B without being captured by all of these cameras.

And even the person buying, who bought that first camera alone might think twice or think, analyze the issues differently if they looked at it from a scale standpoint, or if they said, oh, gee, Ring right now makes it impossible for me to run this without sending all that data to a central point. You know, I might not want to contribute images of the people who visit my house, some of whom will be my friends to a, you know, to a central database and have loss of control over that data.

KAYE

The even bigger picture here though, is that Amazon Ring is fueling a growing public-private video surveillance partnership between homeowners and police — with Amazon as facilitator, and at no financial cost to law enforcement agencies.

Hundreds of police departments partner with Amazon’s Ring public safety network. That allows them to request access to Ring video data from camera owners to help in investigations.

Tyler Chandler says the Mt. Juliet PD is a participant, for example. He says even if they don’t request video from Ring camera owners, often people proactively send the department video footage anyway. Most of the time it’s videos of vehicle break-in attempts, he says.

So what’s in it for Amazon? Police, in effect, help them sell Ring. The company gets public relations assistance from police promoting Ring products and the Neighbors app. And, as reported in Gizmodo and Motherboard, police departments are even asked to follow detailed instructions for how to discuss the Ring partnership. Amazon even supplies scripted talking points and social media posts.

Experts like Tien suggest Amazon Ring, in effect, is a surveillance network with implications for tracking and identifying people that goes far beyond simply fostering peace-of-mind or capturing package or car thieves.

Here’s Tien.

TIEN

You know, you might not think about it as a surveillance network per se, and yet, we also know that Ring is establishing these sort of public-private partnerships and trying to concentrate data towards law enforcement and that changes the character of things because, again, scale, and who knows what.

It’s ironic, but when you have certain kinds of governments or administrations and you say, well look, what happens if they’re collecting data and that gets sent to ICE and you care about not having Dreamers be deported or you’re worried about the way that the federal government handles, you know, deportation, then you might think, oh, police access to this kind of public safety data isn’t just public safety anymore, is it? It also has political implications.

KAYE

In response to this criticism of Ring, Amazon provided an emailed statement, which I’ll read here in full:

Ring takes the safety, privacy and security of our customers extremely seriously, and we build products for our customers and communities, not law enforcement. We designed the Neighbors app to keep residents in control of what information they want to share and with who [sic], and that includes local police. Ring never provides police access to device livestreams, and police have no access to device location, user information, or video recordings unless customers choose to share them. As a customer, you can choose to share videos publicly, or not. You can choose to opt out or decline any requests from law enforcement, and police have no visibility into which customers have received a request and which have opted out or declined. Your videos are yours and how you use them and who you share them with is up to you.

That’s the end of Amazon’s statement. Let’s remember, while camera owners have some control over data captured by Ring, people whose images are captured by those cameras do not.

As the neighbors of Pebble Point discovered, their Ring camera technology only went so far. It’s why they wanted to layer in more surveillance tech in the hopes of having more trackable, identifiable information in the case of future incidents.

The same goes for law enforcement. As we saw with the Kansas City homicide case, or the Detroit case involving Green Light camera still images and facial recognition, police often combine information gleaned from various tech tools to piece together an investigation.

In Mt. Juliet, the police department has done just that – using information from Ring cameras in conjunction with data from their Rekor license plate reader system. Here’s Captain Chandler.

CHANDLER

Sure, we’ve done that before. The footage we’re getting though, is of a suspect in a crime, right? You saw that person walk up to a car door and attempt to burglarize something, or you saw an assault suspect leave a home. And how it could connect is you may get a piece of information off this video, and a piece of information off this video, and a piece of information off this video.

But, for example, a recent incident, they were trying to determine a suspect vehicle and one Ring camera captured the suspect vehicle. That then allowed our officers or detectives to search the Rekor system for that suspect vehicle, and then once you get the suspect vehicle identified, the Rekor system captures the plate.

So, rather, the Ring video didn’t capture the plate, but the Rekor system captured the plate because it’s just more in-depth and more clear. But you got your original vehicle description from the Ring.

KAYE

The world of surveillance tech in cities is as layered and complex as the fabric of urban life itself.

As we see in New Orleans, Detroit and San Francisco, and not-so-urban environments like Pebble Point, TN – surveillance tech and data that affects people and can be used by law enforcement is not always procured solely by government.

Sometimes businesses buy it. Sometimes private entities. Even surveillance tech firms themselves help supply it. Sometimes everyday homeowners chip in.

What is and what is not surveillance tech depends on who you ask and who’s using it. As is the case in Eugene, OR, tech used to make city life more efficient and convenient – even when it has surveillance capabilities and generates new forms of data that law enforcement could access – is not necessarily considered by governments to be surveillance tech at all.

And as we see in Detroit, Kansas City and Mt. Juliet, surveillance cameras paired with facial recognition, cameras combined with license plate readers, license plate readers and data from Ring cameras – these sorts of tech combos could become the norm.

Cities cannot think about surveillance tech procurement or policy in a vacuum. It’s about where the data can flow, who can access it. It’s about where the money comes from and who controls it. It’s about how technologies and data might be used together.

This is our backdrop for the third and final episode of City Surveillance Watch.

[SOUND: Episode 3 teaser]

Join me, Kate Kaye, in our last episode when we’ll learn about surveillance tech rules on the books right now, about how governments are developing tech policy and legislation, how they’re evaluating costs, measuring effectiveness and weighing the impacts of technologies on their communities, and how they’re navigating the complicated issues surrounding tech with surveillance implications.

Until next time.

Podcast

Podcast