Mark Bolinger is a Research Scientist and Bentham Paulos is an Affiliate in the Electricity Markets and Policy Department at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab.

Twenty-five years ago, as wind power began to spread to the Midwest, most farmers were happy to lease their lands to commercial developers, to supplement their income from crops and livestock.

But some wanted more. Inspired by Danish wind cooperatives, some Minnesota farmers pushed for local ownership of wind projects. With the help of state production incentives and legislative goals, they hoped to build at least half of new wind capacity in the 2000s.

While some of these dreams came to fruition, the “community wind” movement had largely fizzled out by 2012.

Fast forward to the 2020s, and community solar is taking off — including in Minnesota, which has over 900 MW in the ground. And while wind power is growing steadily, little of it is community owned.

What happened to community wind? How was it different from community solar? Is it time for a comeback? If so, what can wind learn from community solar?

The wind versus the sun

In a new report for Berkeley Lab, we explored these questions. We are both old enough to have seen both markets in action: Bolinger wrote a number of seminal papers on community wind back in the 2000s while Paulos made grants on the topic when working at the Energy Foundation.

Now community solar is taking off. The U.S. Department of Energy wants to boost community solar from 3 GW to 20 GW by 2025, enough to let 5 million households save $1 billion on utility bills.

So why did community wind fade, and why is community solar thriving?

The first cause is timing. The early 2000s were still early days for wind power, and project economics could be challenging, particularly during “the Great Recession” that hit in 2008. Community solar, meanwhile, post-dates the Great Recession and has capitalized on rapidly falling equipment prices and a prolonged period of record low interest rates during the 2010s.

A second cause is technology-related. Wind projects tend to be site-specific and logistics are more complex. Wind exhibits greater economies of scale than solar, resulting in a penalty for small projects, such as community-scaled projects under five megawatts. As a result, turbine manufacturers focus on bigger projects, rather than selling small batches. Solar is easy to site, quick to build, and the highly competitive and commoditized module business is ready to serve all markets.

But perhaps the biggest difference between yesterday’s community wind and today’s community solar markets is in their business models, which reflect their respective market and policy environments.

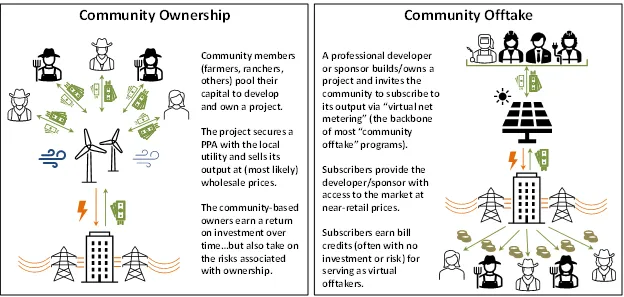

The community wind model largely predated electric utility restructuring, and was predicated on local ownership of a project selling power to a single monopsony buyer.

The community solar model relies on a competitive market environment and state-sanctioned distributed generation programs, where independent developers can “sell” power directly to customers (often through a “virtual” form of net metering).

We call the first model “community ownership” and the other “community offtake.”

When the sole utility buyer of community wind lost interest, perhaps in favor of larger projects with lower energy costs, the model failed. Community solar avoids that problem by providing bill savings directly to an expanding base of subscribers, some of whom might not otherwise be able to access solar energy (e.g., because they rent their homes). While community wind was often viewed as a smaller, less-competitive version of commercial utility-scale wind (a negative connotation), community solar is widely regarded as a more competitive and accessible version of residential rooftop solar (a positive message).

A new sunrise for wind?

But the new “community offtake” business model could also be applied to wind power, right?

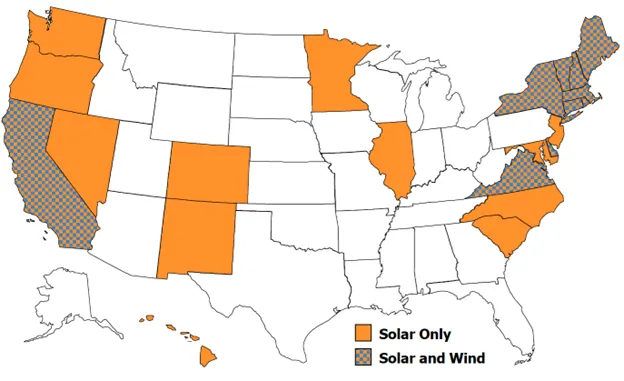

It turns out that many state policies for “community solar” are written to also include community wind. At least 22 states have community offtake programs. Solar is eligible in all of them, while wind is eligible in at least 10 of those states.

But community energy subscriptions, whether solar or wind, need to be financially attractive to buyers. We next looked at project economics to see whether distributed utility-scale wind projects would be competitive with distributed solar.

Recent changes to federal tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act have introduced some intriguing dynamics. While wind projects have traditionally tapped the Production Tax Credit, community-scale projects may be better off relying on the Investment Tax Credit, especially if they can tap the ITC bonuses for domestic content, siting in “energy communities,” and other details.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s long-running Rural Energy for America Program got a big budget boost from the IRA, and may also be a good source of funding for wind projects in rural areas, especially for projects involving both community offtake and community ownership.

State policies that dictate the value of the energy will also be a factor in whether a project pencils out. Looking at the 10 states where wind is eligible to participate in community offtake programs and taking federal incentives into account, we found a number of states — including Delaware, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and New York — where community wind could pencil out and potentially compete with solar within these community offtake programs.

While there is an opening for community wind, it is not a sure thing. Many of the technology-related differences between wind and solar will continue to challenge wind in this application. And unlike the market twenty years ago, community wind now also faces stiff economic competition from solar.

But maybe wind can get in on solar’s game, at least in certain markets, and expand the community of community energy.