Toilet paper may be having its heyday during the coronavirus pandemic, but another household staple that frequently gets flushed is starting to steal the spotlight: disposable wipes.

The disinfectant product is creating serious clogs in wastewater infrastructure, and cities are pleading with the public to stop flushing them as blockages and sewage overflows are on the rise.

It might sound like the start of a juvenile joke, but for U.S. cities it’s no laughing matter. Many water agencies have long waged campaigns asking people to stop flushing personal hygiene wet wipes because they wreak havoc on wastewater systems.

"In the history of wastewater treatment facilities, [wipes] are new consumer products that are incompatible with sewer systems and pumps," Bill Patenaude, principal engineer in the Office of Water Resources at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), told Smart Cities Dive.

The threat du jour

Wipes are trouble for infrastructure in cities of all sizes, and in all parts of the country. They are often reinforced paper or fabric (some contain plastic threads), and are designed to remain intact under friction to keep from disintegrating in consumer’s hands.

"With COVID-19, [the problem] has increased exponentially," Keith Oldewurtel, chief operating officer at Veolia North America, told Smart Cities Dive. "People were always flushing wipes, but at a much, much lower rate and not in as much of a concentrated period of time. When COVID-19 came about and people started using the disinfecting wipes, it exploded."

In wastewater systems, wipes can either wrap around and damage equipment or create sewer line blockages. Many wipes claim to be flushable, but they don’t break down like toilet paper or human waste.

"They don't dissolve. Period," Shaun O'Kelley, operations and maintenance manager at KC Water in Kansas City, MO, told Smart Cities Dive. "Put a wipe in a blender… It won't dissolve. At the treatment plant, it's going to get stuck."

Reports of wipe-related damage came fast and furious last month as the COVID-19 outbreak spread in the U.S., resulting in a spike of individuals using disinfectant wipes. Cincinnati, OH experienced several wipe-related mainline sewer clogs in mid- to late March, said Deb Leonard, communications manager for the Metropolitan Sewer District of Greater Cincinnati.

Two pump failures also occurred during that same timeframe at a Narragansett, RI wastewater pumping station when flushed wipes clogged the pumps’ machinery, Patenaude with Rhode Island's DEM explained. And a wipe-related sewer line blockage in Woonsocket, RI caused sewage to flow into four homes’ basements, which took five Veolia employees about 14 hours to clear and cost about $20,000.

Coronavirus has also prompted an uptick in the use of hygienic wipes for personal cleansing due to toilet paper scarcity. Temporary toilet paper shortages have also forced some residents to resort to using paper towels and napkins for personal wiping, which are also a problem. Though they are made of degradable fiber, they’re thicker and reinforced so they do not disintegrate easily like toilet paper.

"Any paper product that’s designed to be strong is going to be a problem in the sewers," Patenaude said. Kitty litter, feminine products, condoms and dental floss are other commonly flushed items that should go in the trash instead. "The only thing that should be going into toilets is anything that comes out of us and toilet paper. That’s it," he said.

A mounting mess

Wastewater systems are designed differently in communities throughout the country. Some are combined sewer systems that collect and treat wastewater and stormwater together, like in San Francisco.

Under normal dry conditions, the city’s larger infrastructure components alleviate some of the sewer overflow that other cities experience with different systems, Will Reisman, press secretary for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC), told Smart Cities Dive via email.

"Most of the wipes and other non-disposable products accumulate at the treatment plants, where they are separated and treated. As a result of our unique system, we have not noticed any uptick in maintenance incidents related to backups or clogged pipes," he said. Still, SFPUC asks residents not to flush any type of wipe.

Do our sewer system a favor and please dispose of wipes properly where they belong — in the trash. https://t.co/hurPrIUVPS

— SF Water Power Sewer (@SFWater) March 31, 2020

In addition to clogging sewer lines, wipes harm equipment at wastewater treatment plants and pumping stations. The facilities have equipment to pull solid, insoluble materials like wipes out of the water.

KC Water fills a two-cubic-yard dumpster with recovered debris every four days, according to O'Kelley. Despite the removal efforts, wipes can still make their way into the system and tangle in various pieces of equipment. The facilities also typically have grinders that act like garbage disposals to break down material, but disposable wipes' durability challenges the machinery.

"We do use grinders at our pump stations, but they can't always keep up with it," Leonard said. "Sometimes even the grinder goes offline because it gets messed up by wet wipes."

Costly 'fatbergs'

Wipes also absorb grease (which some are designed to do) and are a primary component of "fatbergs." Fatbergs form when people dump cooking fat or grease down the drain – "another big no-no," Leonard said – and it mixes with other insoluble items and solidifies. Sometimes they harden to a consistency similar to concrete.

Removing fatbergs is time consuming and costly. Crews spent weeks working to remove a whopping 130-ton, rock-solid fatberg from London’s sewers in 2017. New York reports spending $18.8 million each year to degrease and unclog sewers affected by fatbergs, repair plant equipment damaged by non-flushable items and transport the items to landfill.

Sewer clogs are difficult to pin solely on disposable wipes, so it is challenging for wastewater management agencies to estimate their direct cost to the system. But they note that cleanup and maintenance costs associated with wipes are undoubtedly growing.

Costs initially are incurred by a city, but it indirectly makes its way to residents as well.

"Over time, there is a cost associated with that, and that added cost is going to have be made up by the rate payer," Veolia’s Oldewurtel said.

It could also have a cascading effect into other areas. "If we have to do that cleaning more frequently because of the wipes, then that means you’re not spending the money somewhere else and you’re going to have other operational and maintenance issues," he said. Costs mount further when considering the number of people that have had to hire services to remove wipe clogs from their residential plumbing and sewer service lines, he said.

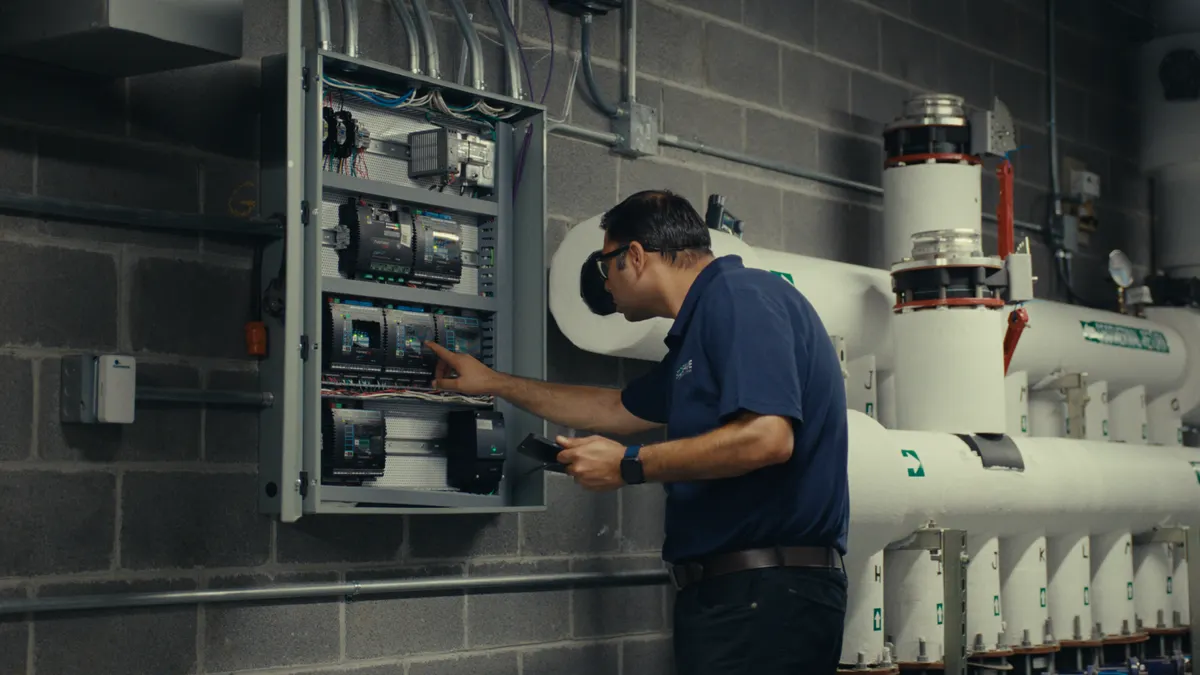

Kansas City and Cincinnati each have smart sewer programs that use sensors to continuously gather data about the stormwater and wastewater system to determine capacity and manage flows. Thus far, those sensors are not specifically used for detecting wipe blockages or fatbergs. They can detect sewer overflows, but it is up to agency employees to find the source. Agencies report that wipe blockages are usually found through regular maintenance inspections, or during system alerts and through citizen calls when overflows occur.

"We want to detect blockages because we don't want sewage going directly to the river. That's what it will do if it runs up in sewers and overflows," O'Kelley said. That's especially the case during rainy periods when stormwater competes with wastewater for space in the sewer system.

"The river goes to the ocean... Do you really want your sanitary products in the ocean?" he said.

Mixed messaging

The wastewater management agencies in Kansas City and Cincinnati were among the early adopters of disposable wipe public education campaigns. Dozens – if not hundreds – of other communities large and small, including Chicago, Boston, and King County in Washington, followed suit or ramped up their intensity in March due to an increase in wipe usage sparked by coronavirus.

As a reminder, please do not flush wipes down your toilet. While we continue to address #COVID19 in the @CityofBoston, please do your part so @BOSTON_WATER is not disrupted.https://t.co/eLOkcptEBw

— Mayor Marty Walsh (@marty_walsh) March 27, 2020

Educational campaigns frequently stick to the easy-to-remember message urging people to only flush the "three Ps": pee, poop and (toilet) paper. The Metropolitan Sewer District of Greater Cincinnati incorporated emojis to keep its messaging lighthearted.

"We didn't want to take a heavy-handed approach to it," Leonard said.

Some agencies say it’s time for wipe manufacturers to step up and change. Manufacturers perpetuate consumer confusion about proper product disposal and bad habits when they label their products as "flushable." Wastewater management agencies stress the stark difference between "can" and "should" when it comes to flushable materials.

"Technically, just about anything 'can' be flushed. A cell phone 'can' be flushed. But it doesn't break down," Leonard said.

Wipe manufacturers and retailers have become the target of numerous class action lawsuits over the past several years as cities take measures to protect their infrastructure. New York City and Washington, DC are two cities that moved to pass regulations requiring packaging for disposable wipes to bear "do not flush" warnings.

Last week, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee signed a first-of-its-kind law requiring "do not flush" logos on disposable wipe packaging. It will take effect in 2022. Similar legislation has been introduced in both chambers of the Minnesota legislature.

Wastewater management agencies say they plan to continue their "no wipes in pipes" campaigns in the coming weeks as the coronavirus pandemic endures. Meantime, they hope manufacturers will get the message of how harmful disposable wipes are to city and residential infrastructure and voluntarily develop better product designs.

"We need the cooperation of consumer product designers and manufacturers. The creativity of the private sector has to be employed to come up with some medium-ground where these wipes break down in the sewers,” Rhode Island DEM’s Patenaude said. "We put men on the moon – we can create wipes that break down in sewers."

To keep up with all of our coverage on how the new coronavirus is impacting U.S. cities, visit our daily tracker.