Despite at least 10 permitting reform bills before Congress, two major federal regulatory initiatives and a bipartisan House caucus call for action on permitting reform, progress remains delayed.

Transmission queue backlogs, system operator capacity shortfalls and increasing outages from billion dollar extreme weather events make the need for streamlined infrastructure approvals irrefutable, analysts, developers and policymakers agree.

“Americans are already experiencing the many devastating impacts of rising global temperatures,” 13 Republicans and 13 Democrats of the Climate Solutions Caucus wrote to House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., and Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, D-N.Y., in November. “Permitting reform to bolster our domestic energy supply” and expand “energy transmission” should be prioritized, they said.

Outdated environmental rules and hundreds of amendments and judicial interpretations built into them are causing “a crippling delay in permitting new projects,” said Alexander Herrgott, president and CEO of The Permitting Institute, or TPI. But “truth-in-permitting” that brings transparency and accountability to the handling of project applications can address “the pinch points in the process,” he added.

The proposed legislation and regulatory initiatives, called a “veneer” by Herrgott, are moving slowly, observers said.

Where solutions are needed

All infrastructure projects must have permits showing compliance with local laws and zoning codes, a 2022 Brookings Institution paper reported. Most state governments require similar permits, and 20 states require environmental impact reviews, according to the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, website.

Large generation or transmission projects may require a regional system interconnection and as well as a federal multi-agency environmental impact study, or EIS, showing broader NEPA compliance, Brookings reported.

Project design, engineering, planning and financing for infrastructure projects can take up to three years and identifying needed permits and the appropriate issuing agencies can take two more years, TPI’s Herrgott told the Senate Budget Committee in July. Federal and state informal pre-applications and formal reviews can add up to six years and construction can be three years, he said.

For generation infrastructure projects that began operating in 2022, the median time from “interconnection request to commercial operations was around 5 years,” according to data from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, or LBNL. That includes local permits, equipment contracts and delivery, offtake agreements and construction, said LBNL Energy Policy Researcher Joseph Rand.

But the biggest obstacle to construction may not be federal reviews.

“Less than 5% of wind and solar projects required a comprehensive environmental review or project-specific permit,” added an August study of 2010 to 2021 federal permits and reviews for energy infrastructure by Professor David E. Adelman, holder of the Harry Reasoner Regents Chair in Law at the University of Texas School of Law. And “half of all EIS reviews take 3.5 years or less,” a September Natural Resources Defense Council paper reported.

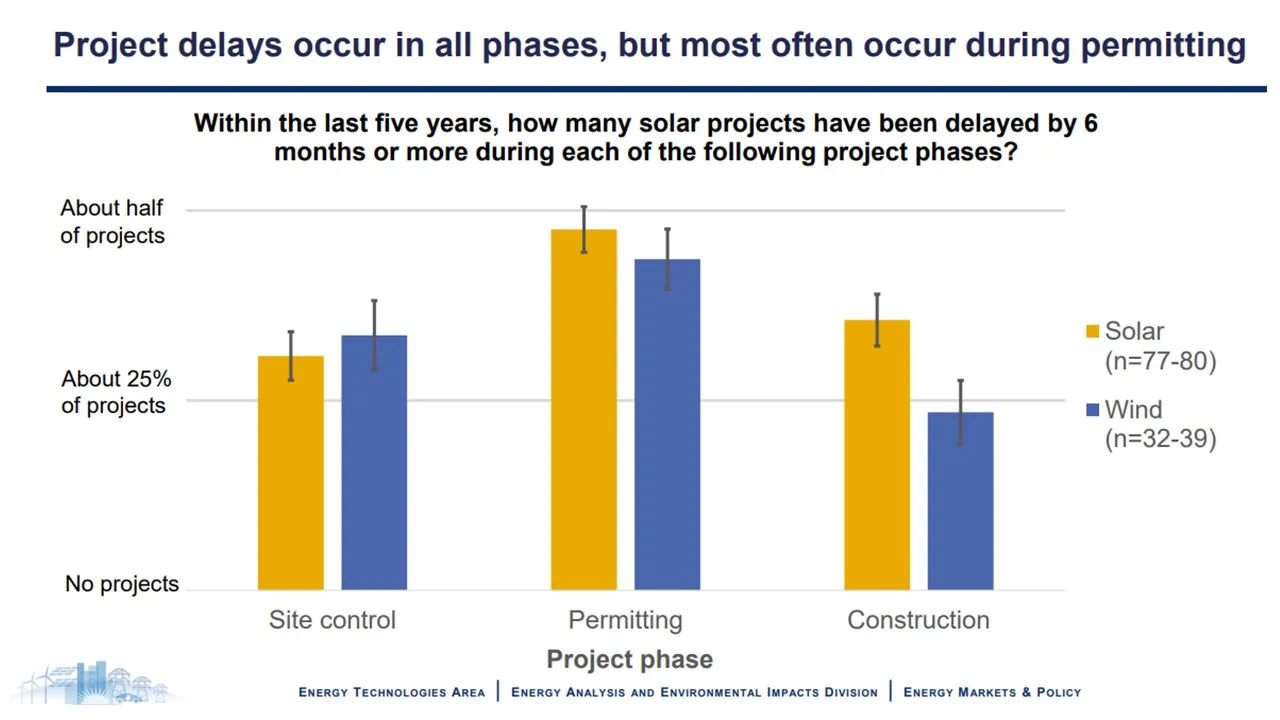

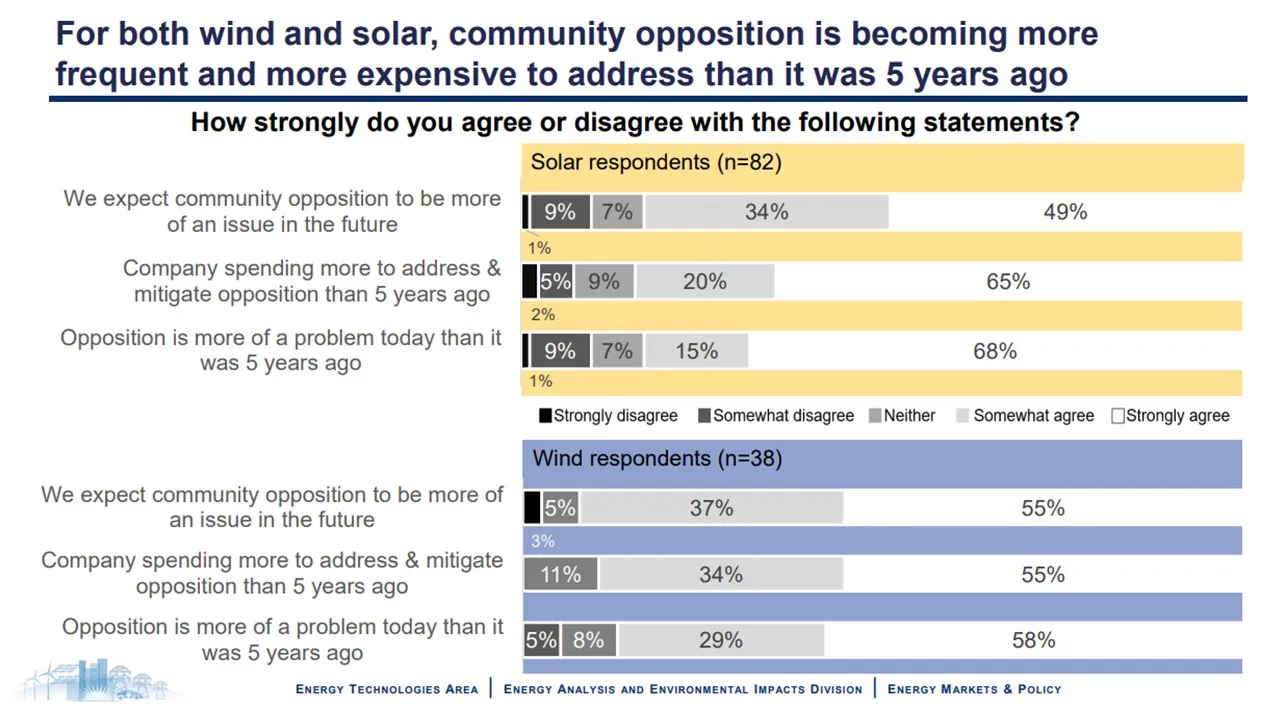

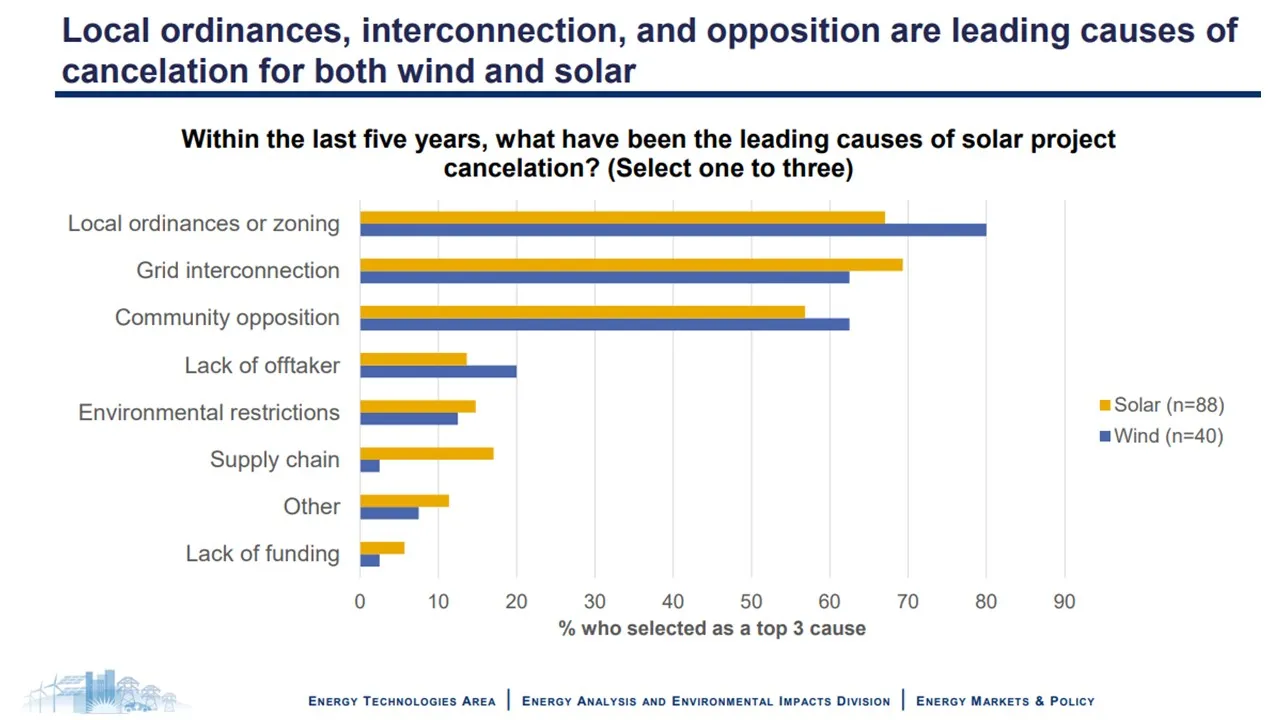

Local opposition, and not federal review, is the real obstacle, data shows. It caused a third of wind and solar interconnection application cancelations, and half of the delays lasting six months or more in the last five years, according to an LBNL developer survey. Cancelations led to average sunk costs of more than “$2 million per project for solar, and $7.5 million for wind,” and local opposition is becoming more common and more expensive, LBNL found.

Though some reforms proposed by federal policymakers address local opposition, most focus on federal permitting processes.

Legislative and regulatory reforms

An emerging consensus among analysts on streamlined permitting conforms with provisions in the Fiscal Responsibility Act, signed into law in May.

NEPA permitting reform proposed by the White House Council on Environmental Quality specifically calls for implementing the act's proposals. One or more of its provisions, including single agency authority, simplified reviews, streamlined timelines and community engagement provisions are in individual bills from Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va.; Sens. Tom Carper , D-Del., and Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii; Rep. Raul Grijalva , D-Ariz. and Reps. Sean Casten, D-Ill. and Mike Levin, D-Calif.

None of the federal bills have emerged from committee, but New York and California have enacted permitting reforms that have proven effective, according to a November Canadian Climate Institute analysis.

New York’s 2020 Accelerated Renewable Energy Growth and Community Benefit Act puts a single state agency in charge of permitting, requires large project permits to be issued within six months to one year, sets a goal of reaching construction in two years, funds community participation in the approval process and requires utility bill credits as benefits to impacted communities.

In 2022, California’s Assembly Bill 205 imposed similar reforms. It makes a single agency responsible for permitting large projects, limits the time to conduct state environmental impact studies to 270 days and addresses local opposition with a community benefit plan and labor and wage protections.

New York’s law has been in effect long enough to prove the value of its reforms, the Canadian Climate Institute reported. Eight renewable projects entirely handled through its central authority took “less than eight months on average to receive a permit” and “only one project took a full year,” the analysis found.

The bigger problem, though, is that “permitting is totally uncoordinated across jurisdictions,” said former Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Chair James Hoecker, now senior counsel and energy strategist with the Husch Blackwell law firm.

The Department of Energy is working on much anticipated federal reforms to provide that coordination.

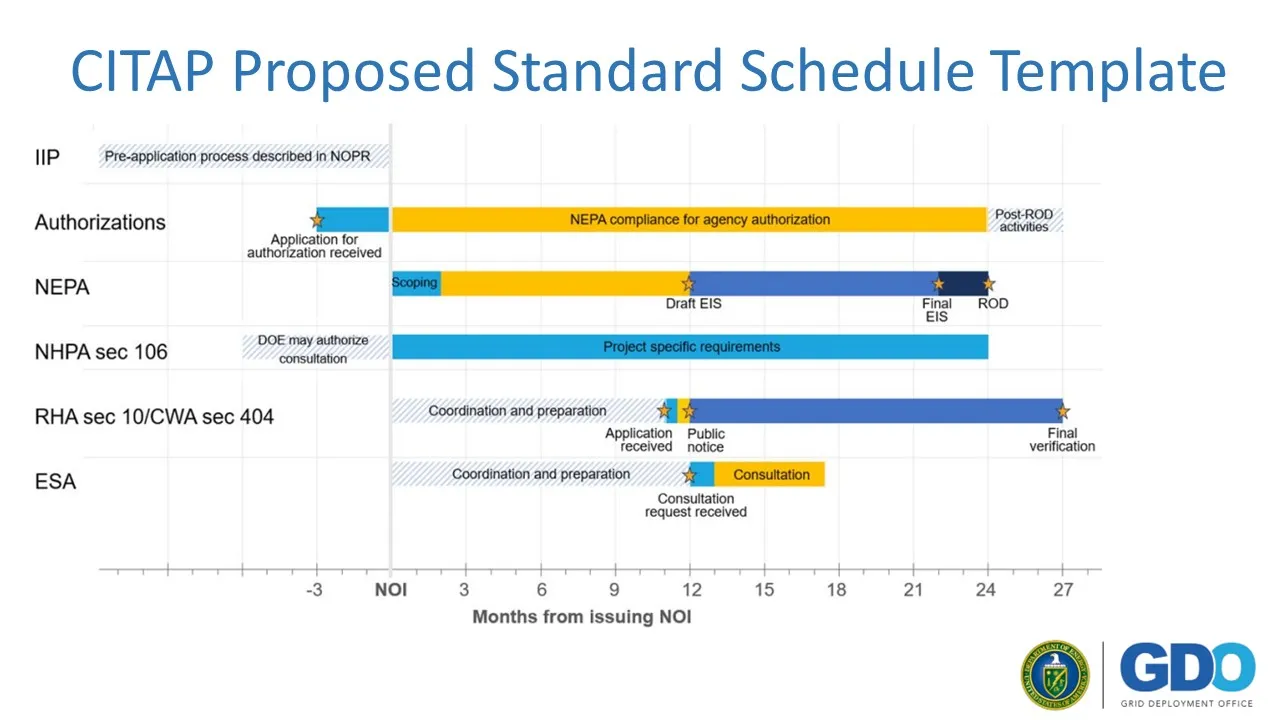

DOE’s proposed Coordinated Interagency Transmission Authorization and Permits, or CITAP, program would streamline environmental reviews and permitting for transmission. It would also support ongoing reform proceedings at FERC to enable more FERC authority on permitting urgently needed transmission.

CITAP’s two-year limit on permitting reviews would not avoid state and local reviews, but would make the DOE Grid Deployment Office responsible for coordinating permitting across jurisdictions and require “meaningful engagement” with local stakeholders, the office said in August.

Its proposed pre-application process can accelerate permitting by demonstrating compliance with federal protections like the Endangered Species Act and the National Historic Preservation Act, added Grid Deployment Office Program Policy Advisor R.J. Boyle.

But significant permitting reform may require more than legislative and regulatory initiatives, observers said.

Community engagement’s importance

All the proposed legislative and regulatory reforms are needed, analysts agree. But reforms that lead to community engagement result in significantly fewer project cancelations, according to 75% of developer respondents to the 2023 LBNL survey.

“The more good suggestions, the better,” because reforms can allow developers to take advantage of the unprecedented levels of federal funding for new clean energy, said Alex Bond, executive director, clean energy and environment, with investor-owned utility trade group Edison Electric Institute, or EEI.

Environmental advocacy group Natural Resources Defense Council is breaking with its past position to agree. “NRDC has historically said ‘no’ to infrastructure that was a threat to the environment,” said NRDC Senior Clean Energy Transmission Advocate Cullen Howe. But pivoting to “yes” by pushing to make permitting reforms more efficient is “a necessary change,” though the reforms will likely force “hard choices,” he acknowledged.

And “where opposition to clean energy infrastructure is growing, hearing appeals from local stakeholders on things that affect their lives is also necessary,” Howe continued. “It could reduce opposition if developers make the benefits of their projects clear,” though “it could slow the process where opponents are well organized and funded,” Howe added.

Environmental laws were designed “half a century ago for infrastructure like fossil fuel plants,” said Harvard Law School Electricity Law Initiative Director Ari Peskoe. Clean energy project reviews “should be different because they don’t create the same problems,” but “there is no magic formula that solves all permitting delays,” he added.

That is why working on better reforms and ways to do more with existing rights-of-way are important alternatives, EEI’s Bond said.

New solutions

Current federal legislative and regulatory proposals do not offer real solutions to permitting delays or use solutions available now, like creating greater transparency and accountability at permitting agencies, TPI’s Herrgott and former FERC Chair Hoecker said.

“CITAP is the veneer of a solution” and the federal bills are inadequate because they both call for accelerating the process but do little to give permitting agencies incentives to resolve impediments, Herrgott said. Faster permitting can be done without more environmental harm, “if there is absolute transparency at the permitting agencies” on project applications, but right now “coordination and transparency are the exception, not the rule,” he said.

“A centrally accessible dashboard can create truth-in-permitting” by disclosing project status and revealing “why and where delays happen,” Herrgott continued. The resulting “accountability and transparency will drive reforms,” he said.

“Judicial appeal is the second part of reform,” because delays should be evaluated by a court “within 30 days” instead of the lawsuits stopping development “for two years and frustrating investors,” Herrgott said. Congress should also update and clarify “obsolete environmental laws governed by precedent that the federal agencies and the courts are struggling to interpret,” he added.

There is also a way to limit the need for permitting.

Using existing ROWs, particularly networks of ROWs like transmission real estate, highways, railroads and pipeline routes, could completely avoid the need to obtain a permit, Hoecker said.

The Champlain Hudson Power Express line to bring Canadian hydropower to New York “is already under construction and includes over 100 miles of railroad rights of way and some highway rights,” Hoecker continued. The SOO Green transmission line to bring Iowa wind to Chicago in 2029, though not yet fully permitted, “might have taken years longer without ROW agreements with Canadian Pacific and other railroads,” he said.

Existing ROWs can be “a major piece of the solution to the transmission development puzzle,” and “help meet the massive challenge of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050,” Hoecker said. But “it will take vision at the DOE and coordination through federal and state transportation departments” to enable it, he added.

The need for “a reasonable, adult conversation about the problems built into environmental statutes is being forced to the surface like a volcano ready to burst,” Herrgott added. “With once in a generation federal funding for clean energy, now is the time to act, whether Congress wants to or not.”