Though 2020 is a year away, cities are already gearing up for what's to become the nation's first digital census.

The 2020 count will be the first to be done largely online, and the run-up has also become heavily digital as governments are relying on new data sources and mapping technology to prepare an advertising blitz to get people to respond.

For cities that have seen an influx of new residents, the 2020 Census is more important than ever, since it determines Congressional representation and the distribution of hundreds of billions of federal dollars for infrastructure, housing, health care and education. But the urgency to get it right on the city level is growing, thanks to what some say are troubling signs from the federal government.

"I'm especially passionate about how important the census is for cities and counties, and I have a lot of concerns with how the 2020 Census will go," said Chris Dick, a former statistician at the U.S. Census Bureau. "A bad Census count means cities won't get their fair share of federal funding, may not get their political representation. And we'll have a poor understanding of who's living there."

Before a massive influx in the 2018 budget, Congressional Republicans had underfunded the Census Bureau compared to the lead-up to previous decades. Several field tests were canceled, and the government plans to hire fewer enumerators to canvass houses than in previous years.

The Trump administration’s proposal to include a question asking whether respondents are U.S. citizens is also of big concern, prompting fears that it could be used to round up undocumented immigrants (that question is the subject of an ongoing lawsuit). A January poll of New Yorkers from Quinnipiac University found that 87% felt undocumented immigrants would be discouraged from participating in the census, while 61% felt that legal non-citizens would be discouraged, potentially leading to a crippling under-count.

That’s put the onus on cities and local governments to convince residents to respond.

"We’re taking an unprecedented role this time," said Julie Menin, Director of the Office of the Census for New York City. "We have to do things a little differently because of the citizenship question. It’s on us to engage the community groups, the faith-based leaders who are the trusted advocates and get them to spread the message."

Data leads the way

Victoria Kovari, who was named last month to lead Detroit’s 2020 Census effort, compares her job to a political campaign. She has to engage the "base" that will usually respond out of civic responsibility, then launch a messaging campaign to reach the hard-to-count populations on the fringes.

For Detroit, both will be challenging. Between 2000 and 2010, the city’s self-response rate dropped from 70% to 64%, the largest decline of any major city (Kovari says the economic downturn contributed to a “chaotic” count). The city also has a diverse population that includes traditionally hard-to-count demographics, like immigrants and minorities, non-English speakers, renters and people living in group housing units.

But if someone is hard to count, then how can you know to reach them in the first place? The answer has come from advanced data maps, building on technology only available in the last decade.

"Maps have always been a part of the census. Enumerators would use tens of thousands of paper maps as their guide," said Linda Peters, who works with data firm Esri on population counts. "2010 wasn’t that long ago, but the tremendous advances in GIS mean our capabilities are way beyond what was possible then."

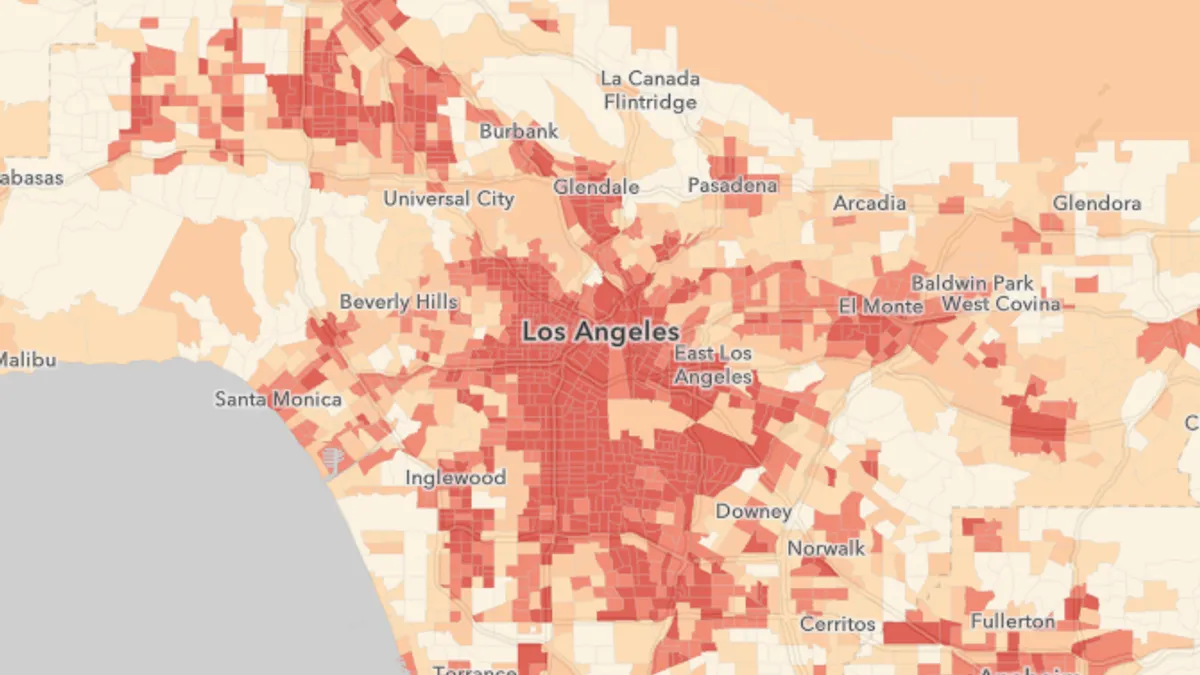

The Census Bureau has released an online tool called ROAM (Response Outreach Area Mapper), an application that uses American Community Survey data to measure how hard-to-count each census tract might be, assigning each a score. Now cities and states are building on top of that base with local insight.

Kovari, for example, is overlaying information like community meeting places and churches that can help get the census message out. Canvassing over the next year will help Kovari’s team add information about neighborhood aspects that might challenge enumerators — like having retirement homes or hard-to-reach doors — and craft a specific plan to reach them.

"We already know where we have a solid presence already and where we’re a little thin," Kovari said. "Our Department of Neighborhoods has been crucial in beefing up our community information. We’re not going to just rely on the scores of the Census Bureau."

In fact, cities say that nothing can replace on-the-ground experience. In New York, for example, when planners compared self-response rates to the Census Bureau’s predictions, they found that some of the neighborhoods projected as troublesome were actually some of the most reliable.

"A place like Jackson Heights, it’s two-thirds foreign born, a lot of people don’t speak English. That’s a place that shouldn’t do very well," said Joe Salvo, the city’s chief demographer. "But we found that trusted voices really got through there, so they had a great response."

Elsewhere, New York neighborhoods with more homeowners and English speakers had lower rates of self-response than largely immigrant ones, a near-reversal of what the Census Bureau would predict.

Based on their own analysis of 2010 Census return rates, Salvo’s team built their own version of ROAM that includes 11 variables such as the percentages of minority residents, renters, non-family cohabitants and people living in poverty. Those variables were then combined into "neighborhood clusters" (for example: Hispanic, renters, poor) reflecting different projected response rates, helping the city know where to target their resources.

Likewise, California’s Complete Count Committee has partnered with Esri to create SWoRD (Statewide Outreach and Rapid Deployment), what they call a "muscled-up" version of ROAM that incorporates 14 different demographic variables, including renting status, broadband access and English proficiency.

"In 2010, we found that we needed improved information sharing," explained Alicia Wong of the California Complete Count office. "With all the advances in technology, we can make sure we’ve got the right people in all the right places."

The maps can also help identify broadband deserts where residents may not have home internet access, which can help them plan to install pop-up booths where residents can fill out the forms, or target advertising on how to complete the census on a smartphone. And once the count begins next April, the federal government will offer real-time response data, helping planners with advanced maps fine-tune their response on the fly.

Getting the message out

Once hard-to-count populations are mapped, the year-long lead-up to the census hinges on an effective messaging strategy, the more microtargeted the better. California will spend more than half of its $150 million census budget on messaging, with a large chunk of that being distributed to community groups. Churches, for example, can be valuable to reach out to some minority communities, while community organizations that work with immigrants can help comfort residents concerned about the citizenship question.

Areas with more young families may see messaging about the role the census plays in Head Start funding, which promotes comprehensive child development, while New York is planning to target coastal neighborhoods with ads about resilience funding.

A new analysis from Civis Analytics offers some messaging guidance. After testing various messages to assess enthusiasm for the census, the most impactful approach was to highlight civic responsibility and the impact on representation in Congress.

One message appeared to backfire: reminding people that their data would be secure (a natural concern with the online count) actually decreased enthusiasm compared to a control group that didn’t see that message.

The Census Bureau said it has been doing everything possible to protect data, though it has not been transparent about what those efforts are as it does not want to give advantage to "adversaries wanting to discredit the federal government." Dick, the former statistician who now works for Civis, said officials would do well to avoid any reminder that data security is a concern, and instead focus on the positives.

“We know that even the way these messages are worded impacts the response,” Dick said. “The census is too important to these cities, this is a once-in-a-decade opportunity to get it right.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misidentified Julie Menin, Director of the Office of the Census for New York City.