For today's buildings owners, the philosophy is often the greener the better. Owners of professional sports stadiums, as it turns out, are no exception. According to the U.S. Green Building Council, there are at least 30 LEED-certified sports venues in use or underway in the U.S., and the organization said that number is growing.

In September, the Sacramento Kings' pronounced its new $557 million Golden 1 Center the first indoor LEED Platinum-certified sports arena in the world and the first sports venue powered entirely by solar energy. Arena designers also repurposed construction materials from the structures that were demolished to make way for the Kings' new home, resulting in more than one-third of the new building’s material recycled from the old ones. Designers even used recycled athletic shoes for the court surfaces.

The arena’s location is green as well. The site selection process, which resulted in a downtown location, took fan travel time into consideration and, by 2020, will have reduced air emissions by 24% and related greenhouse gas emissions per attendee by 36% as a result. This will keep a projected 2,000 tons of greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere each year.

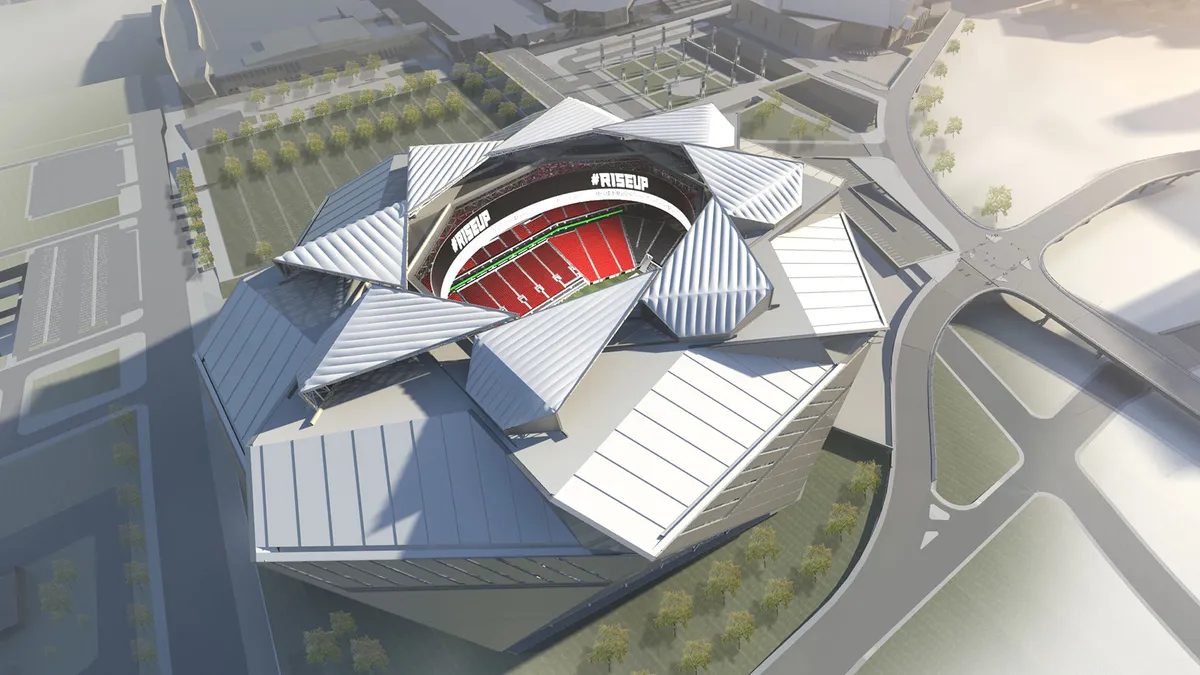

The Atlanta Falcons' new $1.5 billion Mercedes-Benz stadium is also on track for LEED Platinum certification, and the facility will be the first sports venue to earn all of LEED’s water-related credits. The stadium received federal kudos last year when the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy recognized it for its solar-powered electric-vehicle charging stations and enough solar panels to power 160 area homes.

But what, exactly, is it that drives sports facility owners to go green?

Dan Chorost, environmental attorney at Sive, Paget & Riesel, said there are a few reasons. Those include wanting to lead by example, enjoying the public relations benefits, saving money and fulfilling local requirements. The latter was the case for the water capture system at the Barclays Center, in Brooklyn, NY, which is home to the Brooklyn Nets and the New York Islanders.

Chorost said the facility’s 400,000-gallon underground system, which the city required, helps keep stormwater out of the city sewers during heavy rain. Unlike cities with somewhat more modern infrastructure, New York still uses the same pipes to handle both sewage and stormwater runoff, he said, meaning that when public agencies decide to divert water to avoid flooding, there's a chance human waste could be dumped into the East River, the Hudson River or New York Harbor.

The green roof atop the Barclays Center, however, was a choice, and one that comes with benefits apart from aesthetics. The roof, Chorost said, is planted with drought-resistant flowering plants that absorb rainwater as well as help soundproof and insulate the building.

However, the primary driver for stadium owners to go green is the chance to reduce energy consumption and, as a result, lower costs. "The industry has matured so that the prices of solar and other technologies have come down as they [have been] scaled up," Chorost said. "So not only are [owners] doing good for the planet … but [they are also] saving money and saving energy." Plus, the visibility most major sports venues enjoy promotes the idea of sustainability to other building owners and to those who visit the facilities as fans.

Why some stadium owners are holding back

Michael Ahearn, senior vice president of operations for Spectra by Comcast Spectacor, said there are reasons an owner might not choose to go green. Those include capital costs, low return on investment and site or physical limitations, and they often vary based on each owner's priorities.

Spectra manages sports venues, convention centers and other entertainment facilities across the country, and Ahearn said LED lighting is a particularly popular green feature. Owners often reach out to the company for advice on converting their buildings to the new lighting system.

At CenturyLink Field, in Seattle, sustainability was the driving force behind the installation of green features like LED lighting and low-flush toilets, as was the desire to minimize impact on the environment, said Will Pokorny, construction manager at McKinstry. McKinstry was part of the team that built CenturyLink in 2002 and was brought back as part of a modernization initiative to ensure the facility’s systems were as energy-efficient as possible.

"Owners come to us with a vision of reducing energy, adding solar, improving operational efficiency, reducing costs or making their stadium or event center more sustainable — whatever is their primary driver," Pokorny said. "We translate this vision into reality."

Community facilities are going green, too

Sustainability can work for smaller facilities, too. Rockford, IL–based architecture and engineering firm Larson & Darby Group was part of the team that designed the Mega Sports Center expansion for the Rockford Park District at MercyRockford Sportscore 2. The 133,000-square-foot complex includes a large field with room for full-sized soccer play, football, lacrosse or rugby, but it can also be divided into four smaller soccer fields or two softball fields.

Mike Dudek, director of construction administration and sustainability at Larson & Darby, said the cost savings driven by energy-efficient features were what prompted the city to invest in one like the swath of radiant heat flooring that encircles the perimeter of the building's interior and warms the concrete, making it nice and toasty for spectators at about half the cost of traditional heating.

The building's exterior is lined with insulated panels with an R-13 value to keep all that precious heat inside. The design team chose LED lighting, which Dudek said has lightened the cost of its electric load by about 60%.

Natural light and features like low-flush toilets contribute to the savings as well, Dudek said, as did the owner's rep, who was proactive about including such elements in the pre-planning stage.

"[Green construction] is the best money you can spend,” he said. "If you don't think about it at the forefront, it probably won't happen. People have to buy into it."