Editor's note: This is Part 2 in Smart Cities Dive's series on the future of U.S. high-speed rail. Part 1 provides the current outlook for U.S. high-speed rail and its history to date. Part 3 examines the challenges to creating a national high-speed rail network.

It was an audacious idea: build a 200-mph passenger rail line between San Francisco and Los Angeles unlike anything that has ever existed in the United States. In 2008, California state legislators put Proposition 1A on the ballot, asking voters to approve a $9.95 billion bond issue to get the project started. Largely favored by Democrats and environmental advocates, the project also enjoyed the support of then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican. The ballot measure passed with almost 53% of the vote.

But 16 years later, no one has ridden a high-speed train in California. A 119-mile segment of the 494-mile project is under construction in the state’s Central Valley, an agricultural region. High-speed trains aren’t expected to run there until 2030 at the earliest. Still, that hasn’t stopped others across the U.S. from investing, planning and beginning to build high-speed rail projects.

“The time has come for high-speed rail,” investor Wes Edens told Smart Cities Dive. Edens is the co-founder and CEO of Fortress Investment Group, which backs the Brightline West project to connect Las Vegas and Southern California with 200-mph trains.

Advocates cite benefits ranging from reduced highway congestion and greenhouse gas emissions to time savings and job creation. “The more time that you save people, the more likely it is for them to take your train,” Edens said. The sweet spot for high-speed rail lines that will entice private investors are city pairs that are “too far to drive and too short to fly,” he said.

Traditional public transit strongholds are not the only places you’ll find government support of high-speed rail today. The states of Georgia, North Carolina, Oregon, Washington and Tennessee, along with the North Central Texas Council of Governments, are among the entities actively planning new high-speed rail projects. And Amtrak is evaluating a partnership with Texas Central Partners on a Dallas-Houston line. Here is a look at where these projects stand.

California’s big idea faces big challenges

The proposed San Francisco to Los Angeles line, managed since 1996 by the California High-Speed Rail Authority, has a checkered history. Estimated costs have ballooned from $33 billion in 2008 to up to nearly $128 billion in 2024. The authority’s 2008 business plan described a system carrying more than 90 million passengers across an 800-mile network annually by 2030; its latest 2024 business plan now projects 28.4 million riders along a 494-mile network by 2040 — if it can find the money to continue building. “We have some significant financial challenges that are ahead of us,” said Anthony Williams, a member of the California High-Speed Rail Authority’s board of directors and director of public policy for Amazon in California.

California LA-SF high-speed rail project

Delays, cost overruns and management issues came to the fore in a 2018 report from the California state auditor. It faulted the authority for over-reliance on consultants, poor contract management and high turnover among its contract managers. When Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, came into office in 2019, he said in his first state-of-the-state address, “The project, as currently planned, would cost too much and take too long.” He backed away from the aspiration of linking San Francisco, LA, Sacramento and San Diego, committing only to a smaller project in the state’s Central Valley. That’s where construction is underway now, between Bakersfield and Merced, California.

“Historically, doing this kind of thing has never been easy,” said Williams. “We also had some challenges at the beginning about how to get it right.”

The project became the target of some Republicans in this Congress, who added a provision to the House fiscal year 2025 transportation appropriations bill that would prohibit the project from receiving federal funds.

“Most people in this country, when they think about high-speed rail in the United States, tend to gravitate towards [the California project] because that's the one that's been going on for quite some time,” said Greg Regan, president of the AFL-CIO’s Transportation Trades Department. “The problem is that how ambitious it is and has been, it's going to draw a target on its own back.”

Support for the project in Washington has shifted back and forth in the past five years. While the Trump administration tried to kill a previously awarded $929 million federal grant and threatened to claw back $2.5 billion in federal funds from the authority, the Biden administration last year gave it $3.07 billion.

In recent months, the California High-Speed Rail Authority received environmental clearance for the final segment of the LA-San Francisco line and appointed a new CEO, but Williams admits there are still challenges ahead. Currently available, authorized and expected future funding totals $35.2 billion, enough to finish the first segment. But that leaves a $93 billion gap to meet the estimated cost for a line that runs all the way from San Francisco to Los Angeles. “At this time, we do not have a specified timeline for project segments outside the Central Valley, as the necessary funding has not yet been secured,” the authority states in its 2024 draft business plan.

Both the state and the federal government will have to step up their commitments, Williams said. “We're making a promise about how high-speed rail is going to transform transportation and future economic development, particularly in the Central Valley,” he said.

Las Vegas line attracts private investors

While the California project has relied entirely on public funds to date, Brightline West is investing its own capital into a $12 billion project between Las Vegas and Southern California. The project has also been awarded up to $3 billion from the Federal-State Partnership for Intercity Passenger Rail Program and will have access to up to $3.5 billion in private activity bonds from the U.S. Department of Transportation. These bonds are tax-exempt, significantly lowering the cost of capital for Brightline West, which must repay them.

“The private sector can provide a significant impetus,” said Edens. “But especially when you're trying to develop the first [high-speed rail line], government support is necessary. And fortunately, we have a government now that believes in that.”

Brightline West began construction in April. Its 218-mile line from Las Vegas to Rancho Cucamonga, California, about 42 miles east of Los Angeles Union Station, will mainly run in the median of Interstate 15, with intermediate stops in Victor Valley and Hesperia, California. At Rancho Cucamonga, it will connect with commuter railroad Metrolink for those continuing on to other Los Angeles-area destinations. Constructing the line along an existing transportation corridor eased the permitting process and allowed the federal environmental review to speed through. Brightline West aims to complete construction in 2028.

Edens sees “many really compelling city pairs around the country” for high-speed rail and said that “there's lots of capital availability” as well as interest among the investment community to participate in these projects. He highlighted the “Texas triangle” — Dallas, Houston, San Antonio and Austin — as one of the most compelling opportunities.

Texas may be next

A project to connect Dallas and Houston with a high-speed rail line dates back at least 10 years. It saw little progress this decade until Amtrak got involved last year. In an interview with Smart Cities Dive, U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg called the Texas Central project “one of the most promising proposals.”

Amtrak and Texas Central announced in August 2023 that they were evaluating a potential partnership to move the project forward. A year later, Andy Byford, Amtrak’s senior vice president of high-speed rail development programs, announced at the Southwestern Rail Conference that Amtrak is taking the lead on the project, and an Amtrak spokesperson said at the time that the rail company is conducting due diligence. The partnership is subject to a nondisclosure agreement, and Amtrak declined to make Byford available for an interview for this story.

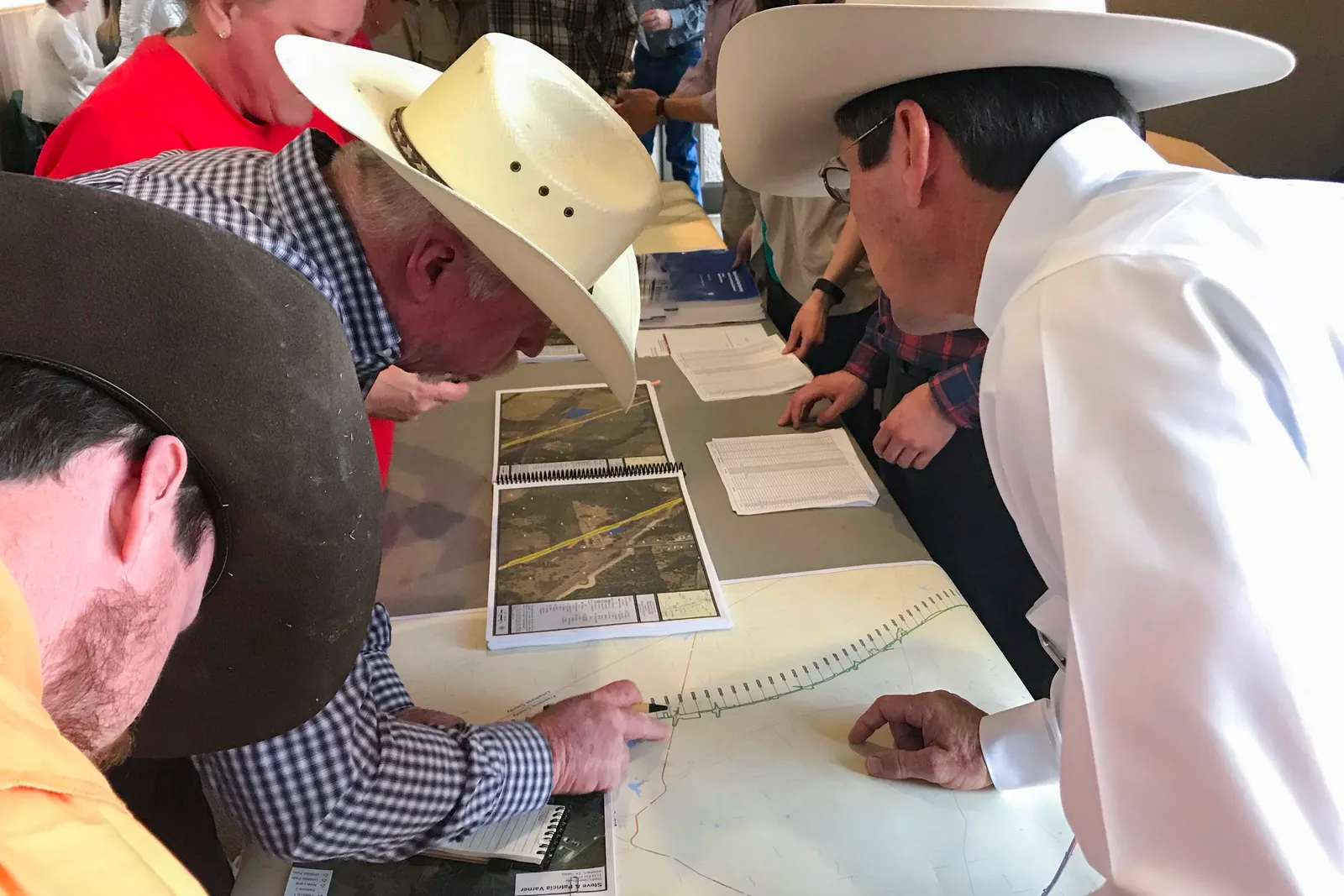

“With Amtrak entering the scene on this, it gives new life to it,” said Peter LeCody, president and chair of Texas Rail Advocates, a nonprofit advocate for high-speed rail in Texas. LeCody said Amtrak has moved the project to the third and final step of the Federal Railroad Administration’s Corridor Identification and Development Program. The program, authorized under the 2021 infrastructure law, helps guide intercity passenger rail development throughout the country. Step 3 enables the project to begin preliminary engineering and environmental work, some of which has been done. According to LeCody, Amtrak is conducting “very extensive conversations with everyone along this route, from North Texas down to Galveston.”

High-speed rail projects in the United States

Four more projects in planning around the country

Amtrak received a federal grant of up to $500,000 to help plan the Texas Central project. Four other projects also received up to $500,000 planning grants last year under the FRA’s Corridor Identification and Development Program:

- The North Central Texas Council of Governments is proposing a high-speed rail line between Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas, a short ride that would allow residents west of Dallas to easily connect with the proposed Texas Central line to Houston.

- In California, the High Desert Corridor project seeks to link the future Brightline West line to the California High-Speed Rail Authority’s San Francisco-LA line in Southern California. It also has state and local funding.

- The states of Washington and Oregon, along with the Canadian province of British Columbia, are exploring high-speed rail connecting Portland, Oregon; Seattle; and Vancouver, British Columbia.

- The Georgia Department of Transportation is spearheading a plan to build high-speed rail connecting Atlanta and Charlotte, North Carolina.

Congress has granted appropriations for two other projects: a proposed Atlanta to Chattanooga, Tennessee, line, led by the Tennessee Department of Transportation in conjunction with the Georgia DOT, and an Atlanta-Savannah, Georgia, line.

Some advocates envision a national network of high-speed rail. “A true high-speed rail network would be enormously beneficial for our economy and for our climate,” Buttigieg said. “It would even be beneficial for our roads because it would reduce the congestion on them.”

But funds for these ambitious projects can be hard to come by, and U.S. political leaders’ attitude toward high-speed rail could determine their future.

To stay up to date with the latest high-speed rail news, see our tracker for high-speed rail projects in the U.S. and subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates via email.