The mayor of Durham, NC isn't afraid to get dirty — literally. Steve Schewel has taken a hands-on approach to smart city leadership, which has included riding along with trash and recycling crews.

In addition to prioritizing the city's waste issues, Schewel has turned to behavioral economics to entice residents out of their cars and onto bikes or buses. Those methods have even included a weekly $163 lottery for residents who choose to ride the bus.

Smart Cities Dive caught up with Schewel, who is up for reelection on Nov. 5., to learn more about his campaign platforms and how he's used social science to implement "smart" initiatives throughout the city.

The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

SMART CITIES DIVE: The UN Climate Action Summit happened [recently], and the U.S. lacked a leadership role in those conversations. As mayor, what kind of pressure do you feel to take action on climate change in lieu of strong federal leadership?

STEVE SCHEWEL: I feel a lot of responsibility to take action on climate change. The inaction of the federal government has only strengthened our resolve here in Durham to take action.

Do you think that local leadership at the city level will be enough to help the U.S. meet the Paris agreement goals without strong federal leadership?

SCHEWEL: No, I don’t think that will be enough. It's critical that cities take a leadership role, but if the federal policy doesn't change, we will not be able to get the job done. Cities can't set national emission standards. Cities cant override lousy federal energy subsidies... Cities can't override drilling for fossil fuels in places where we shouldn't be drilling for fossil fuels. Cities can't redirect government support away from fossil fuels and toward renewable sources like solar and wind.

Cities have a role to play, but we're not going to be able to get this job done on climate unless we have a change in federal policy.

Would you say a lack of federal leadership is one of the biggest barriers for Durham and other cities to meet their climate goals?

SCHEWEL: Yes, I would say that's one of the biggest barriers for sure. For example, if we're going to meet our climate goals, we’re going to have to have a lot more installed solar technologies. And if the federal government was giving the support to those technologies instead of fossil fuels, we would be able to do a better job of meeting our local goals.

I read that you're using behavioral science to get people to stop driving their cars alone to the city center. Why did you choose to use behavioral science methods to change residents' driving habits?

SCHEWEL: We are very fortunate in Durham to have the Duke Center for Advanced Hindsight, which is a fabulous name for a center. It is a real wonderful research and practice center for advancing the insights of behavioral science into public policy.

We have been working with the Center for Advanced Hindsight to try to change the mobility habits of folks coming downtown here in Durham. We want to reduce the number of people driving individual cars into the city center and encourage people to come on buses, to walk or bike. The behavioral economic insights that we're using so far have...had good success.

What behavioral science techniques did you use?

SCHEWEL: They were very simple. We competed for this through the Bloomberg Mayor's Challenge and we are very grateful to have been awarded the million dollars to do this over three years. In the pilot phase ... there was a control group and an experimental group. And with the experimental group, we gave everyone simply a map of how they could get downtown [by] walking, biking or on the nearest bus. [We] gave them information about how long it would take to make that commute and [we] gave them information about how many calories they would burn and how much money they would save from gasoline. In the experimental group, there was quite an increase in the number of people who were not driving their cars downtown.

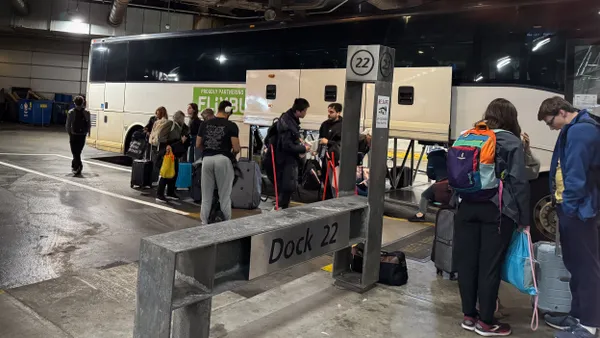

Another [method] was [also with] an experimental group and control group. And in the experimental group, anyone that rode the bus, we offered the chance to enter a weekly lottery to win $163. That significantly increased the number of people taking the bus even though the chances of them winning the lottery weren't that high... Our goal is to decrease the number of trips in individual cars coming downtown by 5% because we want to stop building parking garages. We want to have a positive affect on our climate. That's just the beginning, but that’s our initial goal.

Are you working on any other pilots?

SCHEWEL: We are about to pilot our organic waste recycling program where we're doing food recycling. This is a great smart cities reform. We now have a permit from the state in order to create compost in Durham from a combination of our yard waste, bio-solids from our sewage waste and food waste.

We are doing the initial combination of the bio-solids and the yard waste, and next we will be adding the food waste into that. We will be piloting the food waste collection soon. If it works, it would be a tremendous win.

Organic waste makes up about 25% of our waste stream by weight... We aren't allowed to have a landfill in Durham anymore so we ship our waste and pay for it by the pound to a rural county. If we can get the organic waste removed from that waste stream, not only will it help our environment, not only will it provide compost for people, but it will also save us a lot of money because we won't have to ship that waste and pay for it by the pound someplace else. So I think this is a really potentially big win.

Speaking of waste, I read that you drove with trash and recycling crews to understand solid waste work. What was your biggest takeaway from that experience?

SCHEWEL: It's really hard work… I did not ride one of the automated trucks. Getting on and off that truck several hundred times a day and rolling those carts over is work — really hard work. If it's hot or if it's cold, it's very difficult work and it really gave me a new appreciation for our solid waste employees.

Another thing I learned was that there's good trash and there’s bad trash...as our solid waste director likes to say. There are people who totally contaminate their recycling, for example, and really reduce its value. Or there are people that dump construction waste into their solid waste bin. Things like that make the job really hard. We as residents need to take responsibility for doing right by our environment and by our city and solid waste employees who do this difficult work.

Are there any other initiatives you're working on that you'd like to share?

SCHEWEL: What a lot of people don't realize is that there are thousands and thousands of people in our cities who have lost their drivers licenses… because of a traffic ticket that they have not paid or failure to appear in court. In Durham, this number was 46,000 people and over 1.2 million people in North Carolina have a revoked drivers license. Some of them are still driving without insurance or without a license. Many of them are not driving at all, [which] causes them not to be able to get work.

One of the things we wanted to do was to figure out if we could restore drivers licenses for people to help them get their lives back, especially their working lives. In the past year, with the cooperation of our district attorney and our courts, our innovation team has led the way and we got 55,000 charges dropped for 34,000 people. We [also] got 1.2 million dollars in fines forgiven so we've really done a great job of trying to remove barriers for people to get driving again.