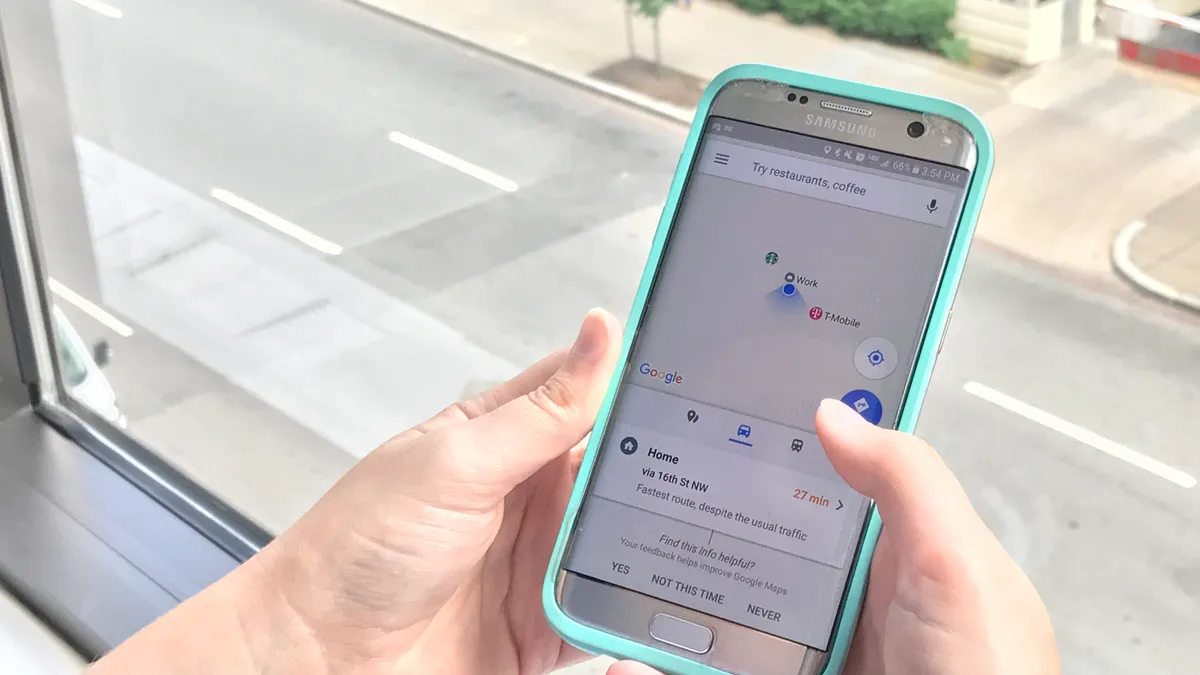

For years, cities have been trying to use data that has sat, siloed in individual departments. Even as that historic data is liberated and made more open, however, more and different types of data are coming in. Since the advent of smartphones with built in GPS, location data, streaming from millions of phones, has created new opportunities – and headaches – for cities.

Out of this new data, location intelligence (LI) has emerged, a field that uses geospatial information to tackle problems. Governments are using location intelligence to see where residents are, and to improve and hone projects, especially within public safety and transportation.

Using location information, cities can effectively create digital nervous systems of how their cities run. Cities can use maps overlaid with data points, sourced from connected personal devices, to analyze problems and find data-driven solutions.

Massive amounts of data coming in, from smart trash cans, to smart traffic lights, to GPS data from mobile devices, are an as-of-yet untapped resource for cities to find solutions to problems that can’t be solved with traditional city management tools.

"Location intelligence is a device for answering more forward-thinking questions," said Santiago Giraldo Anduaga, director of product marketing at CARTO, a location intelligence software company. "It’s the new requirement and new standard for city services in general."

Early adopters

Companies, which typically have their own sources of data and can move faster than governments, are already proving the case for location data, according to Eddie Copeland, Director of Government Innovation at Nesta, a U.K. based innovation center.

Uber and Airbnb already use LI as a core part of their company. Other organizations like Wikipedia and Tripadvisor prove that sourcing data from the outside is profitable.

"In light of this, many cities' approach to open data can be seen to have a glaring shortfall: the flow of information is in just one direction," Copeland said in an email. "Businesses, charities and citizens can receive data from government. But there are few official, standardized and automated mechanisms to provide data to government and each other. That is a huge missed opportunity."

While still in the early stages, there are examples of cities using data from companies.

In Bath, England, a community initiative group used data from the fitness app Strava to see the most popular cycling routes. It’s helping decide where new bike lanes would be most practical, not just what the local government thinks might be good. Uber, despite earlier resistance, makes aggregated level data on journeys available through its Uber Movement platform, letting interested parties get some insight into traffic flows around a city.

There is, however, a deficit in how cities use data. Most government datasets are unused, and over 90% of government data isn’t even open. Accessing the streams of smartphone data, which have the added issue of privacy, is going to be a major hurdle for cities.

Privacy and the new frontier

Residents have specific uses where they feel it’s acceptable using location data. In the 2017 Unisys Security Index, 84% of respondents supported the idea of their smartphone or smartwatch notifying police and EMTs of their location in an emergency. However, only 32% said they supported police being able to monitor their location at anytime, according to a Unisys press release.

Alex Howard, deputy director of the Sunlight Foundation, said the foundation would like to see privacy by design become the default – but knows there are long discussions about how and when smartphone data should be shared. He said the type of data that hasn't historically been available to governments is "going to be a friction point for the rest of our lives."

An approach that might work is being pursued by Decode, a European Commission funded project that aims to give individuals tools that could control whether they keep their personal data private or share it for the public good. But city access to citizen data could go beyond that.

"From Nesta’s point of view, we hope that cities will be encouraged not just to crowdsource data from citizens via their smartphones, but also to solicit their views, ideas, expertise and opinions in the form of digital democracy apps," Copeland said.

Tools like D-Cent (which Nesta worked on) and DemocracyOS help citizens get involved in local politics and civic life on a digital platform, for example.

There is plenty of location data still coming, some of which won’t be sourced from citizens and residents. Sensors and trackers added to city-owned vehicles or light poles can create real-time data of where people are and when. Companies will continue to find ways of sharing – or selling – data with governments. Autonomous vehicles will process, and create, untold gigabytes of data every minute as they scan environments and make decisions. It may not be long until intelligently-processed location data revolutionizes decision making.

"This is a new frontier for people," Anduaga said. "Cities are a meta-creature where small changes are having profound effects."