Dive Brief:

- A Los Angeles program designed to divert nonviolent 911 calls related to people experiencing homelessness to unarmed mental health professionals saw 173 deployments in its first five weeks, as of early March, according to the mayor's office.

- The Crisis Incident Response through Community-Led Engagement (CIRCLE) pilot began in Hollywood and Venice in late January, making crisis-response teams available 24/7. The crisis-response teams include an outreach worker, a mental health or behavioral health clinician, and a community ambassador – in addition to a daytime team that builds trust with the unhoused community and refers community members to service providers.

- “We have to stop expecting police officers to answer for every type of social situation,” Los Angeles City Council President Nury Martinez said in an email. “Police officers are not social workers, outreach workers, mental health specialists, or what our community needs when facing a non-violent crisis.”

Dive Insight:

LA’s new program is one of many alternative policing models cities have implemented since the summer of 2020’s nationwide racial justice protests following the murder of George Floyd.

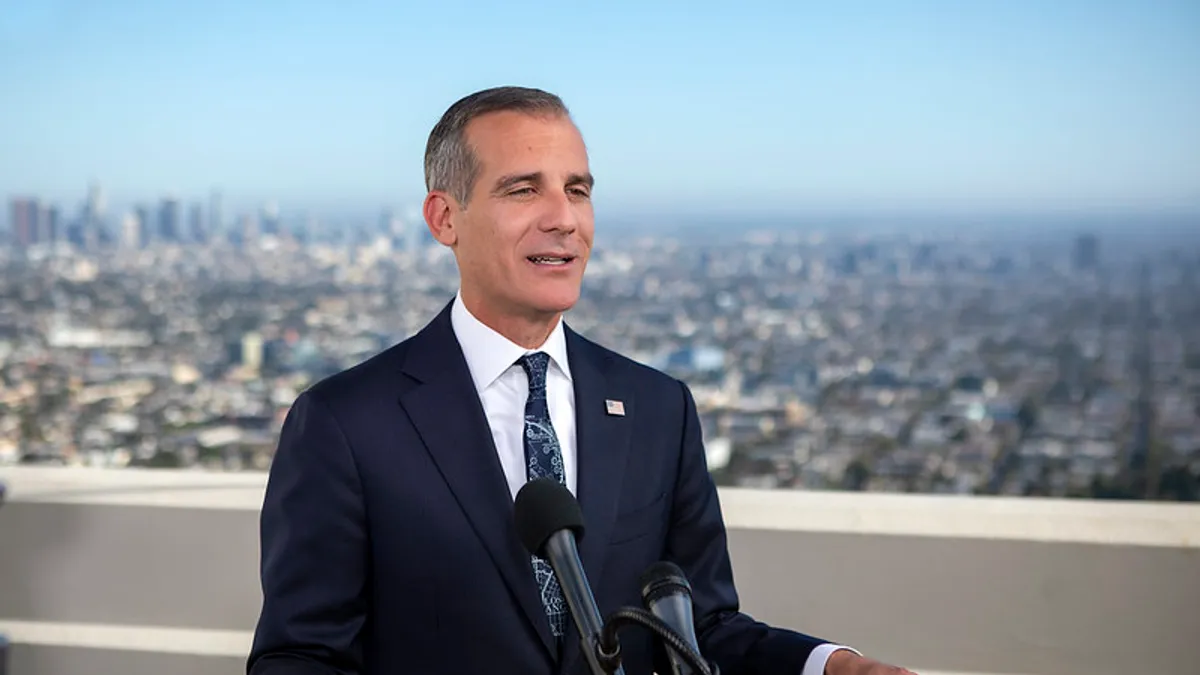

While addressing problems associated with answering mental health calls with law enforcement, the pilot is a move toward Mayor Eric Garcetti’s ultimate goal of ending homelessness in the city, he explained when first announcing the program in November.

Lena Miller, CEO of service provider Urban Alchemy, a Los Angeles-based organization that runs some of the city’s interim housing facilities and a mobile shower and restroom program, said in the November announcement that the redesigned emergency response system would “appropriately and compassionately respond to people experiencing homelessness.”

Howard Henderson, the founding director of the Center for Justice Research at Texas Southern University, said the CIRCLE program would allow both mental health professionals and police officers to respond to emergency calls more appropriately.

“It’s going to provide an opportunity for credentialed, experienced professionals in the space of social work to respond to calls that sometimes, unfortunately, end in the wrong situations,” said Henderson. “Police officers are trained to control situations more so than to understand the underlying issues that created those situations.”

Last summer, the Seattle City Council voted unanimously to officially re-route emergency 911 calls not related to fire or medical response from the Seattle Police Department to the City of Seattle Communications Center. The center, staffed 24/7, now handles approximately 900,000 calls annually.

Likewise, since 1989, Eugene, Oregon’s own alternative policing model – Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) – has organized teams of medics and crisis intervention workers to respond to nonemergency medical and social calls instead of activating police officers. CAHOOTS responds to 17% of 911 calls, annually saving the police department budget $8.5 million. In 2019, out of the 24,000 calls answered by CAHOOTS, less than 1% required police backup.

While Henderson said one downside could be potentially endangering mental health clinicians, he said the new program is far more positive than negative.

“Most of the time officers respond, it has nothing to do with stopping a crime and everything to do with underlying issues people are suffering from,” Henderson said. “Police for too long have served as the front line for the mental health system. The first person people in crisis should see shouldn’t be a police officer but someone who’s trained to mitigate these issues.”