Editor's Note: This piece was written by Johanna Hoffman, a writer on climate change and its impacts on the built environment. The opinions represented in this piece are independent of Smart Cities Dive's views.

It wasn't supposed to happen like this. Coffey Park, one of the most devastated neighborhoods in the recent fires raging across Northern California, was an urbanized place. Downtown Santa Rosa was right down the road, the highway just a short drive away. The real high-risk zones were the areas closer to the regional parks and forest edges. Coffey Park — built in the middle of the city, full of paved streets, cul-de-sacs and single-family homes — was a safer bet. It said so on the hazard maps.

We know now that the maps were wrong. Two weeks since the deadliest fires in California history began to burn, Coffey Park looks like the aftermath of a nuclear explosion, its streets and homes rendered to piles of cinder and ash, its residents suddenly homeless. Amidst all this destruction, new disturbing reports are emerging. Due to those low-risk ratings on the fire hazard maps, Coffey Park was somehow exempt from state fire regulations. Moves that could have made the area more resilient to flames and heat weren't enforced. Before this year, the kinds of fires that tore through Santa Rose weren't just unlikely – they were unheard of.

But not everyone was so surprised by the October firestorms. For fire scientists, these levels of destruction are rare but predictable events, the product of problems with the ways we measure and mitigate risk in California. Techniques used to create fire hazard maps used across the state rated denser developments as unburnable, placing neighborhoods like Coffey Park in less severe risk zones, where more stringent fire regulations weren't required. So how did we get this so wrong? How did the rest of us fail to notice what some of these researchers so clearly saw?

"We know now that the maps were wrong. Two weeks since the deadliest fires in California history began to burn, Coffey Park looks like the aftermath of a nuclear explosion..."

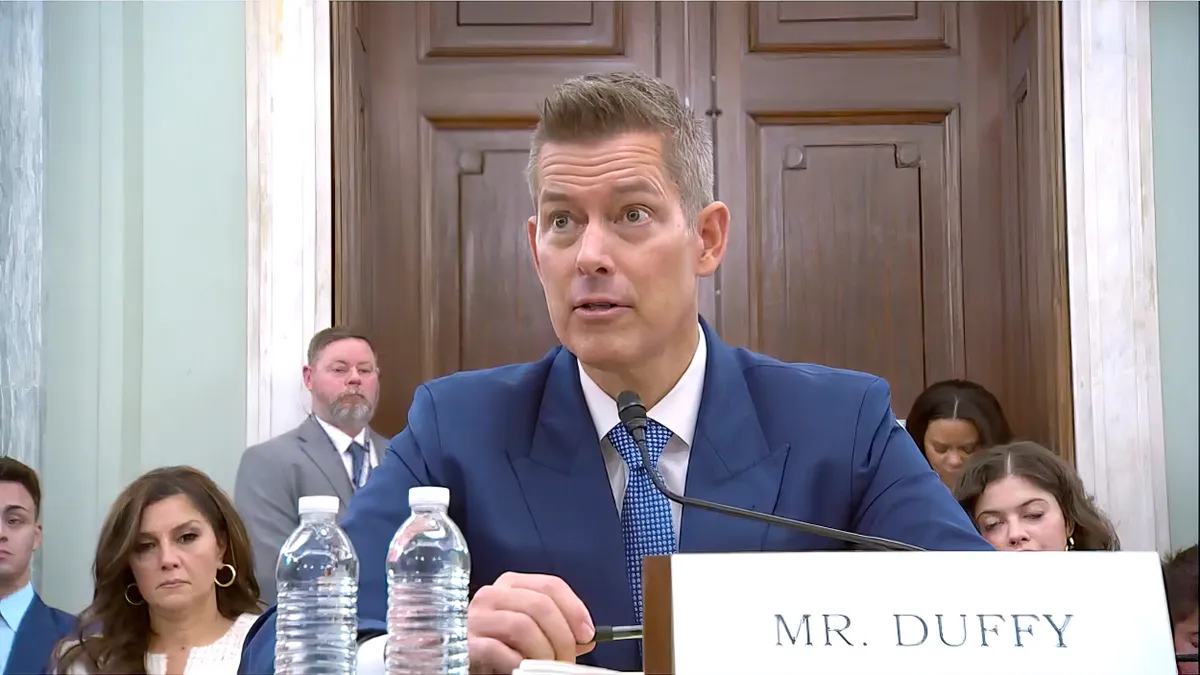

Johanna Hoffman

It turns out that we have an unfortunate habit of overlooking risk in this country. Houston’s flooding vulnerabilities were well known for years before Harvey devastated the city this summer. The Army Corps of Engineers published a study in 1995 that outlined New York City’s risk to hurricanes, predicting the extent to that Hurricane Sandy would destroy the region nearly two decades before it struck. Facing a new reality is scary, time-consuming and often expensive, making scientific findings all too tempting to address later down the road.

This isn't always the case. There’s precedent for cities and regions to re-evaluate risk and create effective feedback loops between the scientific and planning sectors. Take the saga of California earthquake policy following San Francisco’s Great Quake of 1906. The disaster decimated the city when it struck, setting off fires that lasted for days, killing thousands and leaving nearly three quarters of the city’s 400,000 residents homeless. The most immediately devastated areas were places built on fill – former marshes and coves filled over with sand and mud into new swaths of shoreline. While they’re everywhere in the modern world, fill sites become dangerous in earthquake country. Softer materials can shake so much during a quake that they temporarily liquefy. When the 1906 event hit, these filled-in sites were the first to crumble.

Scientists had been predicting the devastation for decades. Edward Holden, an early pioneer of seismic study, wrote an article in the 1870s specifically identifying how treacherous “the made land” was. While his findings were eventually honored as key foundations of earthquake research, few were interested in the late 1800s. Even after the 1906 event proved Holden tragically right, San Francisco officials refused to take earthquake risk seriously. During the aftermath of the disaster there was no talk among city leaders about developing new building codes, or staying away from filled in land. The goal of rapid reconstruction trumped all earthquake concerns.

It was two decades before things began to change. The transformative moment happened in 1925, when Santa Barbara was hit with a tremor that shook the coast from Orange County to Watsonville 240 miles north. As the town set about rebuilding, city workers drafted a short paragraph, a building code appendix laying out provisions that would “provide adequate additional strength when applied in the design of buildings or structures.” That little slip of paper was the moment of change, the first open acknowledgment on American soil that earthquakes were risks worth addressing.

With each new earthquake, state regulators, scientists and engineers found more ways to work in concert. More codes appeared. A 1933 quake in Long Beach led to seismic standards for public schools. A 1964 event in Alaska in 1964 resulted in a presidential decree to create better earthquake predictions. A relatively small 1971 quake in the San Fernando Valley killed dozens and destroyed swaths of infrastructure, inspiring new codes to reinforce older buildings. By the time the Loma Prieta earthquake struck the Bay Area in 1989, it wasn't the catastrophic disaster it could have been. Structures were more stable, buildings stronger, and power lines less brittle. Tragic fatalities were relatively few and daily life more or less resumed within a week.

The story is proof of what we’re capable of when serious problems hit. The more researchers learned about earthquakes in California, the more policy makers distilled and spread the knowledge to different sectors. New structural codes influenced engineers, architects and construction managers. Zoning rules highlighted risk on everything from hospitals to schools to corner store bodegas. Public awareness of the fact that the San Francisco Bay is earthquake country began to spread, until it became the foundation of the story of what it means to live next to the Golden Gate.

But motivation only goes so far. While zoning and building technologies have no doubt improved since 1906, the Bay Area is in some ways more at risk from earthquakes than it was a century ago. With trillions of dollars of real estate and public infrastructure located in vulnerable earthquake zones, future devastation could be catastrophic.

And there’s the rub. Even when the information is right there in front of us, acting on that information is hard to do. Being proactive in the ways we plan our cities is a battle against inertia. Fixing the problems might be too expensive, politically trying or emotionally taxing. Change too often feels like too much of an inconvenience.

Which is what happened in Santa Rosa neighborhoods like Coffey Park. Fire hazard maps are re-drawn infrequently in California — the last for Sonoma County where Santa Rosa is located were made over seven years ago. Intervening years comprised some of the most serious drought conditions in the state’s history. Yet none of those changes were incorporated into new maps, leaving communities largely unaware of the growing risks facing their homes. The story of low fire risk in urbanized areas never changed.

Given the extremes and uncertainties that climate change is throwing our way, we can’t afford to overlook risk. We can't use obsolete data. We have to find ways to make our planning processes more agile, more able to adapt to conditions on the ground. We have to invest in regular, ongoing risk assessment for a range of natural hazards. We have to continually redefine our parameters for what constitutes vulnerability in our cities.

We’ve done this work before in California. It’s time to take what we’ve learned in the past and update it for our future. If we don’t, the fate of Coffey Park will be the sign of what’s to come.