As the driving remains as a top mode of transportation in the U.S., pedestrians are increasingly at risk of injury and death — forcing cities to play rapid catchup to make their infrastructure safer.

A new report from Smart Growth America found there were 12,057 pedestrian deaths in 2016 and 2017 combined (6,080 and 5,977 deaths, respectively), the two highest totals on record since 1990.

The threat has been rising since a low of 4,109 deaths in 2009, a more than 35% increase. Over the past decade, pedestrian fatalities have happened at a rate of 13 per day, according to the report, which drew data from the federal Fatality Analysis Reporting System.

"The bottom line is: we are killing more people walking," said Emiko Atherton, the Director of Smart Growth America’s National Complete Streets Coalition on a press call.

The problem, the nonprofit group says, is a legacy of infrastructure that hasn’t kept up with a population that wants — or needs — to walk. While some cities have invested heavily in bike lanes, public transit or new mobility options, many still lag behind, with insufficient sidewalks that can leave pedestrians at risk. And even Vision Zero projects that seek to eliminate traffic deaths aren’t moving rapidly enough to counteract an increase in vehicle miles traveled.

As new mobility options like shared bikes and scooters expand in cities, advocates warn that not enough is being done to design roads that can accommodate the full variety of travelers, leaving sidewalks and bike lanes crowded.

That’s especially pronounced in low-income and minority neighborhoods, which traditionally see less infrastructure investment. African Americans and American Indians were more likely to be at risk as pedestrians. Charles Brown, a researcher at Rutgers University’s Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center, said that reflects the higher share of minority residents who have to walk to work, even in neighborhoods with "a lack of sidewalks and overall connectivity" and a "lack of complete streets."

Smart Growth America found that the most dangerous states, accounting for population, were concentrated in the south. Orlando, FL was the nation’s most dangerous city (adjusting for population), just as it was in a similar 2016 report. In fact, Florida accounted for the six most dangerous metro areas, and eight of the top 10.

It’s a problem that the city is all too aware of, and is actively working to fix, explained Billy Hattaway, Transportation Director for the City of Orlando since 2016. "We did not want to see this reputation continue," Hattaway said, leading the city to adopt a Vision Zero plan. That’s included investments in more bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, and redesigns of major roadways to expand sidewalk access, reduce driver speeds and offer safer places for pedestrians to cross.

Although Orlando still has a ways to go to shed its pedestrian safety problem, there are models to follow. Design tweaks like narrowing lanes or bumping out sidewalks can force drivers to reduce their speed, while protected bike lanes and crosswalks can create a safer environment. Detroit last year kicked off a construction project that will eliminate two lanes from a seven-lane thoroughfare to make it safer for pedestrians, similar to road diets in cities like Los Angeles. Elsewhere, cities like Portland, OR have reduced speed limits or have bumped out curbs.

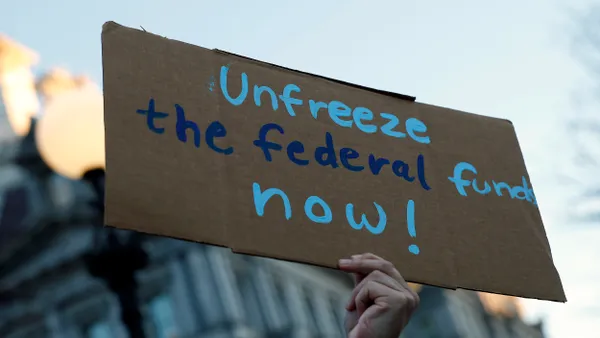

But those require investments and foresight, and Smart Growth America is pushing for the federal government to lead the way. Hattaway called on the U.S. Department of Transportation to loosen restrictions on some safety funds that could be used for education purposes, to help give citizens and planners a better idea of how to make safe choices. With Congress set to consider a potential infrastructure bill, as well as a reauthorization of the regular highway funding bill, Atherton said legislators could adopt a national complete streets policy that would push pedestrian safety directly into the infrastructure decision-making process.

"Until we truly prioritize the safety of the most vulnerable people who use our streets, we will continue to see this preventable epidemic continue," she said.