In 2017, electric vehicles began to present state policymakers with regulatory turmoil previously reserved for rooftop solar.

The estimated 765,000 U.S. electric vehicles (EVs) remain a very small percentage of the 250 million-plus vehicles in operation. And the almost 200,000 new EVs sold last year in the U.S. represent a tiny fraction of the 17 million-plus new cars that rolled off U.S. lots last year.

But almost every major auto manufacturer has public plans for an EV model by 2020, according to PlugInCars. And a 2016 Bloomberg New Energy Finance report showed EVs reaching cost parity with conventional vehicles between 2022 and 2026.

Just as when rooftop solar began to boom between 2012 and 2014, state legislators and regulators are responding to the rising customer demand for EVs with a flurry of policymaking activity. But whereas the rooftop solar battles often divided utilities and environmental organizations, the two are finding new common ground in transportation electrification.

The rise of EV policy

There were 227 state- and utility-level actions related to EVs proposed, pending or decided during 2017, according to a new national policy review from the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center (CETC). The legislative and policy actions covered by the review are wide ranging and include studies of EV impacts and incentives, charging station buildout, and EV-specific rate designs.

As with rooftop solar, some proposed state policies would act to slow the growth of electric vehicles. Special fees, which act as disincentives by adding to the total cost of EV ownership, were the most common EV-related policy proposal in 2017, according to a CETC report.

This is especially problematic for environmental advocates because the EV value proposition is just beginning to attract a market beyond first-adopter climate and plug-in vehicle activists. Many are discovering that EVs’ approximately $1/gallon equivalent fuel cost translates to $3,500 in savings over the car’s life if the gasoline price is $2.50/gallon. At a gas price of $3.50/gallon, the savings go to $9,000.

There were also 2017 policy trends working in favor of electric vehicles, CETC reports. Work on EV rebates and investigatory efforts into the effect of EV growth on electricity load were the second- and third-most common policy actions last year. Efforts to ease barriers to charging station infrastructure buildout by utilities and to test rate designs that benefit both EV owners and utilities completed the top five trend list.

The CETC report reveals a crucial way the growing EV policy action differs from continuing rooftop solar debates. While both deal with the growth of a distributed energy resource, utilities and environmental advocates are often allied on issues related to transportation electrification. Opponents to EVs, often representing or funded by the oil and gas industry, remain. But they now have the electric utility industry to contend with rather than only a handful of disruptive startups.

The EV policy scene

The CETC review covers policy for vehicles fueled entirely by electricity (EVs) and for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, which can alternate between conventional and electric engines. It also covers policy for EV charging stations and other supply equipment.

Of the 227 legislative and regulatory actions in 43 states and the District of Columbia in 2017, 70 were changes to the regulation of electric vehicles in 34 states. They included registration fees, electricity resale rules and siting of charging infrastructure. Financial incentives, including cash rebates, were the subject of 53 actions in D.C. and 19 states.

Market development policies were the subject 36 actions in 17 states. There were 27 studies or investigations of transportation electrification in D.C. and 20 states. Utilities or legislatures in D.C. and 17 states took 24 actions on vehicle or charger infrastructure deployment. And EV-focused rate design was the subject of 17 utility or legislative actions in D.C. and 13 states.

EV fees

There were 28 actions taken in 19 states that created or amended EV-related fees. The new charges are being imposed in states like California and Hawaii, which have relatively high EV penetrations, and in states like Tennessee and Indiana, which have very small market segments, said Autumn Proudlove, manger of policy research at the CETC and lead author of the report.

EV fees can often act as an alternative for funding that vehicles usually pay through the federal gas tax, said Heather Brutz, CETC clean transportation project manager. But EVs are a small portion of that, she said, and gas tax revenues are also falling because of public transport and more efficient conventional vehicles.

It is not “an inherently bad thing” that states are thinking about alternative funding in a changing market and thinking ahead to when EVs reach significant penetrations, she added. “The question is the level of the fee.”

Utah’s wide-ranging Senate Bill 136 includes a proposed $150 annual fee, one of the country’s highest. Its sponsors argue the fee is necessary because EV drivers use transportation infrastructure but do not pay their share for it through gasoline taxes.

Sierra Club Utah Chapter Director Ashley Soltysiak told Utility Dive the fee represents far more of a burden than EVs, at less than 0.5% of Utah’s vehicles, impose on the state’s roads.

Rocky Mountain Power, Utah’s dominant electricity provider, has a time-of-use rate in place to support EV growth. Senior Environmental Analyst James Campbell recently told a legislative task force the utility supports the fee. In the same testimony, however, he urged the legislators to also provide a rebate to “offset” the fee.

Some fees are supported by oil and gas industry-backed organizations like Americans for Prosperity, according to the NY Times. Their efforts could be motivated by a forecasted oil demand drop of 2 million barrels/day in 2025 caused by EVs, the Times added.

Sierra Club Clean Transportation Campaign Director Gina Coplon-Newfield said advocates were able to turn back fee proposals in some states last year.

Along with California legislation increasing its zero emission vehicles goal to 50% by 2025, the state increased its EV registration fee. “But it won't go into effect until 2020 and it won’t be put in place until an investigation of EV impacts is completed,” Coplon-Newfield told Utility Dive.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court struck down H.B. 1449, which would have imposed a $130 annual fee on EV drivers, because its language violated the state constitution, she added.

But a new and “exactly the same” version of 1449 was just introduced, Sierra Club Oklahoma Chapter Director Johnson Bridgewater told Utility Dive, demonstrating the fight over fees will go on. The new fees “are totally out of line with what gas-burning vehicle owners pay in taxes,” Bridgewater said.

Plug In America Policy Director Katherine Stainken said another fee imposing a disincentive on EV drivers is the road usage charge.

South Carolina’s H.B. 3516, passed in May 2017, imposes a $120 road usage charge on EVs, in addition to the vehicle registration fee, CETC reported. It follows Oregon as the second state with a road usage charge now in place, according to information from Plug In America. Five other states are running pilot programs and several more are doing road usage charges feasibity studies, Plug In America reported.

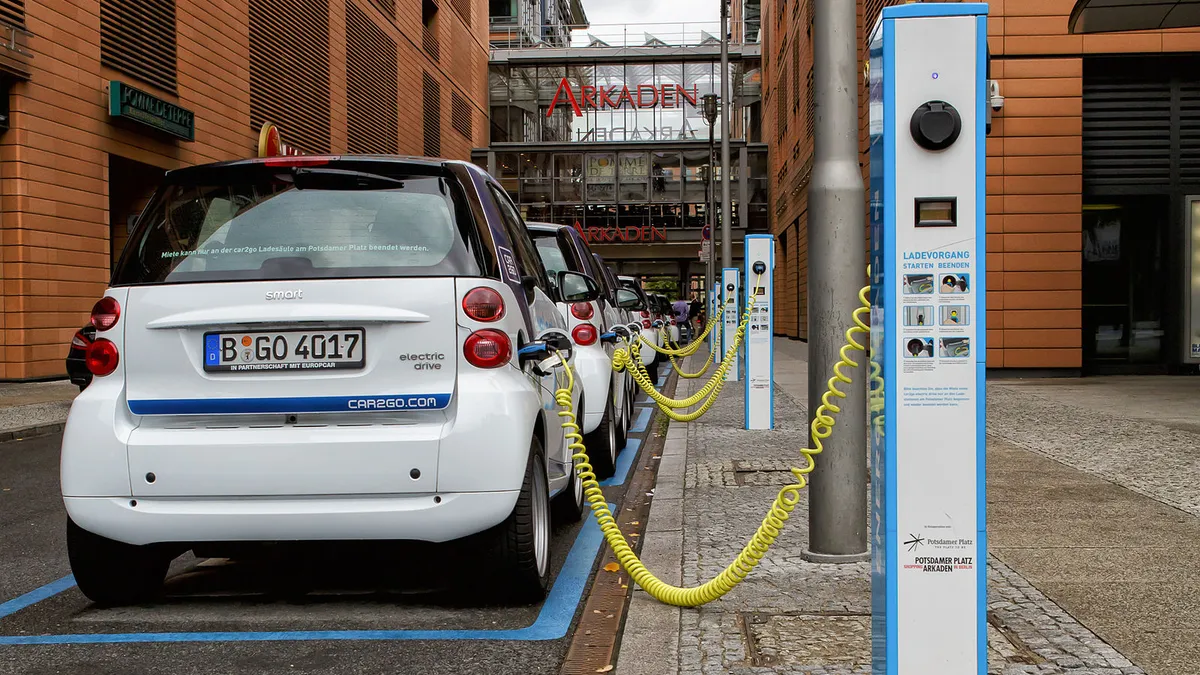

Charging stations

A key emerging policy issue confronting electric vehicles is the role utilities should play in the investment and ownership of charging stations. That question was raised last year in D.C. and nine states.

Approximately $137 million was requested by 13 utilities in 2017 for EV charging. Regulators approved four requests for almost $88 million. Almost $35.5 million in requests from seven utilities is still pending. Only two requests, totaling just over $15.5 million, were denied.

Charger ownership is a controversial question because some private sector charger providers are concerned about regulated utilities’ competitive advantages. But many EV advocates argue that utilities are uniquely positioned to drive deployment and break through a key barrier to transportation electrification growth.

CEO Brett Hauser of Greenlots, a charging station software provider, recently told Utility Dive that utilities can be pivotal because they can “ratebase the charging infrastructure upgrades and consider what is best for the community.”

The 2017 endorsement of utility involvement by 29 private providers and advocacy groups in the Transportation Electrification Accord was a signpost, Plug In America’s Stainken said. Its 11 principles describe how electric transportation can have economic benefits beyond the vehicle sector and support a more reliable and affordable grid.

“Under appropriate rules, it is in the public interest to allow investor-owned and publicly-owned utilities to participate” in building EV charging infrastructure, the accord declares.

Policy proposals from utilities will mean the installation of thousands of new public charging stations, Sierra Club’s Coplon-Newfield agreed.

The question of utility involvement often came up in broad grid modernization and general rate case debates, CETC’s Proudlove said. In National Grid-Rhode Island’s rate case, it proposed an $11.55 million investment to deploy fast charging infrastructure for public use, CETC reported.

Nevertheless, regulators continue to be cautious about allowing utility investments, Proudlove said. Utilities' participation in the charging infrastructure buildout could be seen as an intrusion into the private sector EV charger market by regulated entities with unfair competitive advantages.

Eversource Energy’s $45 million charging infrastructure proposal was approved by the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities, but only with strict limitations, she said. Except in under-served areas, the utility may deploy and ratebase only infrastructure up to the station. Charger deployment was left for private providers.

Missouri regulators denied Ameren’s $570,000 proposal to deploy and ratebase charging infrastructure, ruling the regulated utility could not compete in that marketplace, CETC reported.

Pat Justis, energy services manager for Ameren Missouri, emailed Utility Dive that the utility continues to work with customers who want charging stations.

CETC’s Brutz said Arkansas’s S.B. 272, enacted last year, allows private sector charging station providers to resell electricity without having to meet burdensome rules meant for regulated utilities. A similar Alabama proposal is supported by Plug In America.

“In those states, there is an attempt to provide a narrow exemption to rules prohibiting private sector companies from acting as utilities by reselling electricity. The new guidelines will explicitly allow EV charging, but keep things like solar leasing out," Brutz said.

A program from Consolidated Edison, New York City’s dominant electricity provider, will support charging station deployment through a unique rate design change. It will allow a seven-year respite from a portion of its demand charge to businesses that install chargers.

Everybody loves rate design

The 17 actions in 13 states on electricity rate designs that support EVs and charger deployment caused minimal controversy, Proudlove said. The common theme was time varying or time-of-use rates.

Many proposals included pilot projects to identify what peak periods and on-peak-to off-peak price ratios customers respond to, she said. “The heart of rate design is getting EV owners to charge during off peak times and avoid charging during the system’s peak demand.”

Xcel Energy filed a redesigned residential rate pilot with Minnesota regulators after its first try at a rate to manage EV charging failed to attract significant customer participation, Proudlove said.

Andrew Twite, senior policy advisor with Minnesota environmental advocacy group Fresh Energy, said the new rate relies on faster, smarter chargers designed to better engage customers. And the new chargers have two-way communications capabilities that will allow the utility to eventually move to managed charging, he emailed Utility Dive.

Managed charging allows the utility to time the vehicle’s charging to support grid operations in return for protections and compensations to the driver, Twite added.

Plug In America’s Stainken said interest in managed charging is growing.

Sierra Club’s Coplon-Newfield agreed. In addition to directing new electricity sales to utilities’ lowest demand periods, managed charging allows utilities to take advantage of periods when “there is an abundance of low-cost renewable generation,” she said.

CETC’s Brutz and Proudlove said this type of endorsement by EV advocates is a key example of how they and utilities are finding common ground. Utilities see new electricity sales, a rate base expanded by the cost of charging infrastructure, and systems made more reliable and affordable with managed charging.

It's a "win-win," Brutz said. It's also why opponents of transportation electrification are up against serious competition.