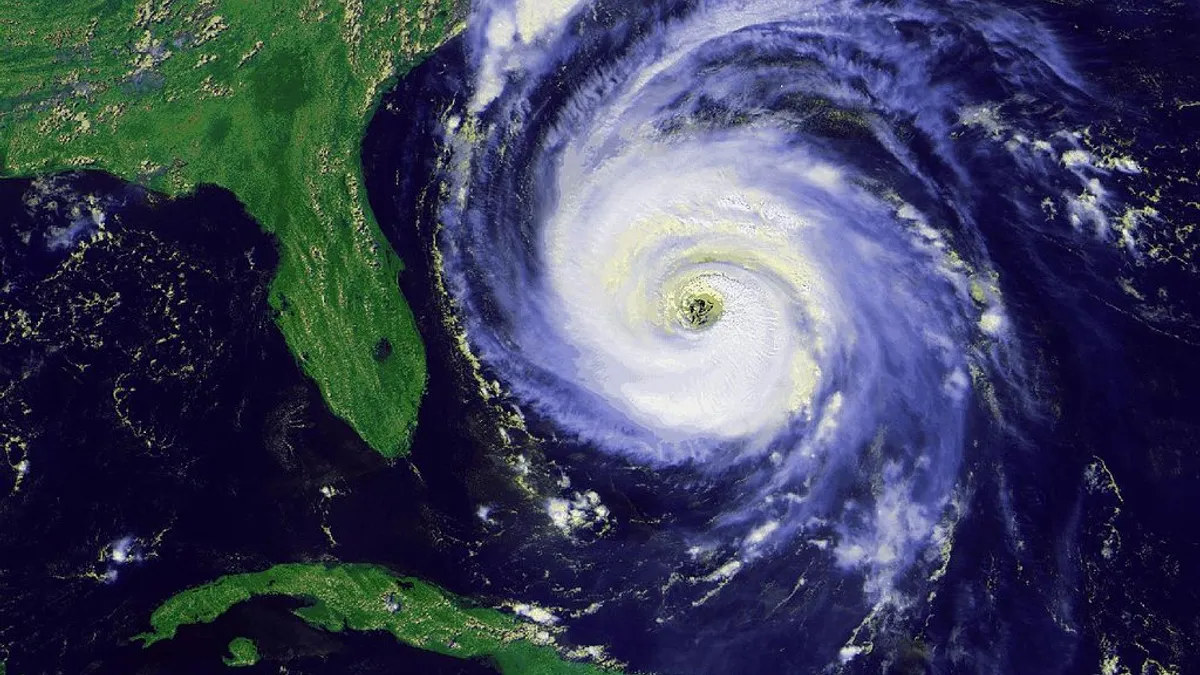

As of July 7, there have been nine weather and climate disaster events in 2017 that saw losses exceeding $1 billion each across the United States, according to NOAA — marking a trend that will likely continue to grow.

From 1980 to 2016, the annual average number of billion-dollar events is 5.5, and that number jumps to 10.6 events when the window is narrowed from 2012 to 2016. Against the backdrop of this growing number of disasters, Trump’s stalled trillion dollar infrastructure plan and the continued dismantling of climate change policy put in place by the Obama administration, cities are now learning how to counteract these growing threats without federal support. Many cities are turning to other partners to work on their resiliency efforts.

That trend influenced the programming at the Rockefeller Foundation summit in New York, part of the Foundation's 4-year-old 100 Resilient Cities (100RC) project. 100RC works on these issues, providing funding and strategic planning for chief resilience officers (CROs), and facilitates how cities can work together and with private companies to better incorporate resiliency. At the event, Ernst & Young and 100RC released a study called ‘How can cities build resilience thinking into their infrastructure projects?’, that looks at how cities are tackling some of the biggest issues.

The study, which questioned 400 people across Ernst & Young and 100RC’s networks, found that city governments think they understand the challenges of urban resilience better than they actually do, with only 30% of private sector agreeing that cities understand the work around urban resiliency.

"The government talks the talk, not necessarily doing the walk," said Bill Banks, global leader on infrastructure at Ernst & Young and one of the authors of the study. "A politician would rather a cut a ribbon on a new highway than on a new flood levee."

The problem can stem from politicians looking for benefits that can occur in one political cycle. Most strategic planning that happens in cities is on a timeline that is not long enough to tackle climate change.

"We need to be patient and think about the long-term impact of intervention and not just in the three- to five-year time frame," said Elizabeth Yee, vice president of city solutions at 100RC and another author on the study.

While discussions of future proofing and resilience can garner positivity, execution is not necessarily happening quickly. Even when plans are created, actions can be slow to follow.

“It’s a question of will you have a resilient city or a shiny resilience plan?” Banks said.

But there are also times when the private sector is scared to overscope on an RFP, as under most procurement rules those proposals won’t be accepted. The study found that both the public and private sector agree there is insufficient incentives to incorporate resilience thinking into infrastructure.

Some cities are further along than others. Miami, which is experiencing a higher rate of sea level rise than most areas, has spent a lot of time and resources to understand coastal flooding and put in a lot of money to protect Miami Beach, including a $400 million project to raise roads and do other work that will help with rising sea levels.

But basic resiliency planning from tornados in Oklahoma to hurricanes in Miami is more similar than it is different. Cities part of 100RC are able to share their strategic plans and build off of each other's work.

"Making a city resilient, at least the broader steps, are the same," said Scott Tew, executive director for the Center for Energy Efficiency & Sustainability at Ingersoll Rand.

Short-term disaster planning, like creating a system for during and after the event, and making sure critical services will be available, are methods cities have considered for a long time. But for planning for the slow creep of climate change, most progressive cities are using best practices that are not focused on a single event. It requires an audit about your current state, and use of masterplan with planning for decades out.

"You can’t do this day of or week of," Tew said.

For big, long-term plans, cities must get creative with funding projects that will make cities more resilient. Banks noted that finding ways for the private sector to get more benefits from the infrastructure is a potential way to fund these projects. An example could be if a developer builds levees and the land value goes up.

“It’s trying to incentivize the private sector to be an active participant in these endeavors and pioneer resiliency,” Banks said.

Currently, cities are paying out for climate change and disasters as it happens, proving to be an expensive endeavor. A new type of incentive structure that brings in private investments can help cities move from a reactive to a preventative model.

“I’ll declare success when an investor says 'I see the resiliency benefits and I’m going to invest,’" Yee said.