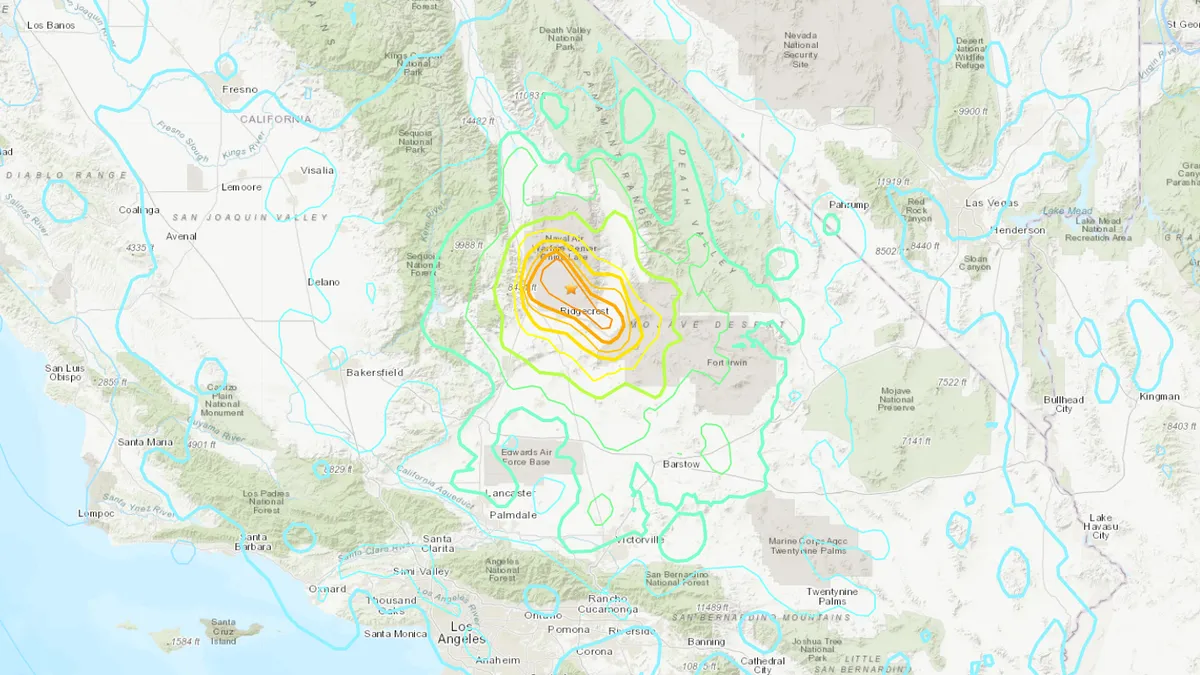

The Ridgecrest earthquakes in Southern California shook most of the state, as well as parts of Arizona, Nevada and Mexico, when three initial shocks of magnitudes (M) 6.4, 5.4, and 7.1 reverberated through the Garlock fault area in July 2019.

There is now a 2.3% chance that a section of the Garlock fault will see an earthquake of M 7.5 or greater in the next year, which has tripled the chance of a large earthquake on the San Andreas fault region, near Bakersfield, to 1.15% in the next year, according to a recent study in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. In turn, cities are faced with an increased need to prepare for such a disaster.

Earthquake risk and the need for community preparedness goes far beyond California, however. Injection of produced water associated with oil and gas extraction triggers earthquakes in Oklahoma and Texas, while parts of the Midwest and South are at risk due to the New Madrid Seismic Zone in Missouri and a major fault near Charleston, SC, said Scott Brandenberg, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Los Angeles. Brandenberg specializes in research around geotechnical earthquake engineering.

"You can’t really find a place in the U.S. where earthquakes are not a hazard that has to be considered when we design and build infrastructure," he said.

A look at SF's building resilience plan

To prepare for the powerful shocks of a high-magnitude earthquake, cities must first prioritize building resiliency.

"There's a recognition that we're not going to make our infrastructure earthquake-proof. There's just no way that that's affordable. So resilience is the key," Brandenberg said. "Resilience is not about preventing damage from happening. It's about being ready so that you can recover quickly without significant disruption to society."

San Francisco could be seen as a case study for this building preparation. Years ago, the city developed the Community Action Plan for Seismic Safety to address local earthquake risk, assessing different types of property and how they would recover, said Bill Barnes, senior advisor of policy and communications for the City and County of San Francisco.

The city has focused particularly on soft story buildings, which are structures with multiple levels that have a hollow floor such as a parking deck. Many of these buildings are home to residents, so not retrofitting these properties could lead to loss of life and housing, Barnes said.

To mitigate this, officials developed the Mandatory Soft Story Retrofit Program (MSSP) in 2013 to support tax-exempted alterations that can seismically strengthen these buildings. Completion of the work done in that program is expected by September 2021.

"Nobody wants to spend money to fix something to protect themselves against what seems like a hypothetical hazard," Brandenberg said of cities’ requirements to retrofit buildings. "Some of the reinforced concrete buildings can cost millions of dollars to retrofit. So I think these are really good ordinances. These fixes would never happen without the government mandate, but it's not without controversy."

San Francisco is also one of the first U.S. cities to study the risks of earthquakes on tall buildings and develop a safety strategy for this type of infrastructure, Barnes said.

"Urban planners and others say we should build taller buildings because we can take advantage of infrastructure and transit and all the reasons why you would have dense housing in the urban core,” he said. “But then a question came up as well as we're building this: How do these buildings perform in an earthquake?"

San Francisco voters also approved a $682.5 million Earthquake Safety and Emergency Response bond in March that reinforces critical infrastructure, such as 911 call centers and high-powered water systems for fire outages. Neighborhood health centers, which are mostly run by the city, are also receiving upgrades such as emergency power through the bond.

In all, San Francisco allocates millions per year to earthquake preparation, but understanding where to invest that money is a difficult decision that many cities and counties face amid preparation, Brandenberg said.

"It's such a complicated problem because all of these systems are interdependent on each other,” he said. “For example, we need electricity to run pumps to move water. A lot of the time, those are managed and operated by different utilities, so getting them to work together is a challenge. If the electricity goes out, then we can't move water. That creates problems for firefighting. It's just so complicated. So the cost there is actually pretty hard to even calculate ahead of time."

Preventing post-earthquake fires

In addition to the risk of crumbling infrastructure, earthquake shocks can rupture gas lines that cause fires. In some cases, the shocks can simultaneously break water lines and hinder firefighting efforts, as was the case of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that killed more than 3,000 people.

After the 1994 Northridge earthquake that shook the San Fernando Valley, the County of Los Angeles instituted a requirement for homes to have automatic gas shutoff valves. Los Angeles is now working on the ability to quickly turn off city-owned gas lines and other critical facilities if an earthquake is imminent, Brandenberg said.

"If we can prevent those things from having the damage result in adverse consequences, that could be a real benefit of early warning," he said.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power is also replacing some of its big water lines with high-tech, ductile iron pipes that can safeguard underground water distribution in the case of an earthquake.

Preparation in the COVID-19 era

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has heightened the consequences of a natural disaster on a city, as strained hospitals are already struggling to meet the demand of those in-need. Local government budgets are also constricted, which could slow any existing progress on resiliency initiatives, Brandenberg said.

Barnes said the pandemic hasn’t stopped any earthquake projects so far, but that could change as COVID-19 continues to spread across the U.S.

"As the economy slows, the budget for the city will be reduced," Barnes said. "Capital projects are one of the first things that often get delayed because it doesn't require layoffs of staff or anything like that. So we will wait and see on whether or not there's a federal stimulus or whether or not there's an effort at the state level to help local governments. That's the big picture question going forward."

Correction: A previous version of this story had misidentified the location of the 1994 Northridge earthquake, which occured in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles County.